Monetary ignorance, monetary transmission, and a great time for macroeconomics

What do we really know about how (if) higher interest rates reduce inflation? A lot less than you think.

There is a Standard Doctrine, explained regularly by the Fed, other central banks, and commentators, and economics classes that don’t sweat the equations too hard: The Fed raises interest rates. Higher interest rates slowly lower spending, output, and hence employment over the course of several months or years. Lower output and employment slowly bring down inflation, over the course of additional months or years. So, raising interest rates lowers inflation, with a “long and variable” lag. “Monetary transmission” complications build on this basic story. They spell out channels by which higher interest rates lower different categories of spending, or how lower output and employment affect inflation.

The trouble is, standard economic theory, in essentially universal use since the 1990s, including all the models used by central banks, don’t produce anything like this mechanism. We do not have a simple economic theory, vaguely compatible with current institutions, of the Standard Doctrine.

The sign is wrong, in two central ways. 1) It’s really hard to get inflation to fall when interest rates rise. Theories that do get interest rates to fall do not embody the Standard Doctrine, rather using utterly different mechanisms. 2) It’s really hard to get future inflation to fall, the long and variable lags. The theories that get inflation to fall at all want inflation to fall immediately when the interest rate rises, and then inflation rise over time. In addition, almost all current theories mix a fiscal tightening with a rise in interest rates. The rise in interest rates by itself has essentially no power to lower inflation.

My goal is to explain all this in simple intuitive terms. Implications and motivation — monetary transmission and why this is a great time for macro — follow at the end.

Dedicated blog readers will be familiar with some of this material. A lot of this comes from “Expectations and the Neutrality of Interest Rates.” I write again as I think I’ve found better simpler and clearer ways to explain it all, and important context.

This is a long post. Substack cuts off email posts at a certain point. In the past I’ve made multi-part posts so you’d get everything in email. This time I’m going to try one post. If you’re reading in email, it will invite you to click to come to the website to see the whole thing. Please do. That leaves a more coherent longer version on the website.

Money

In the old days, we thought about monetary policy by thinking about money. You might naturally want to reach for this story. I think a cheshire-cat memory of this story motivates much belief in the Standard Doctrine.

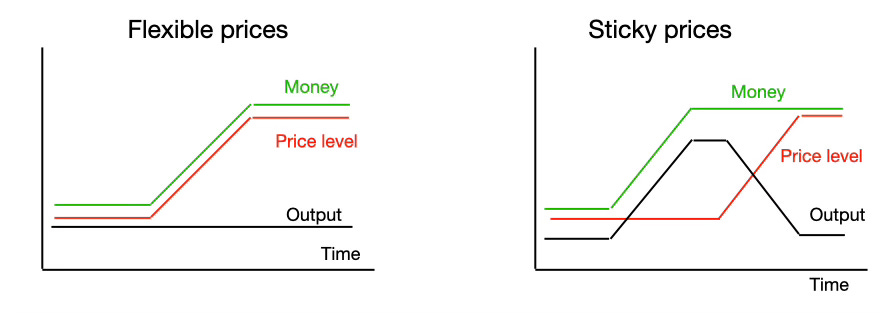

People want to hold more money if their nominal income is higher, due either to higher prices or higher real income. (Throughout, nominal income means the current dollar value, real income adjusts for inflation.) Turning that around, if the Fed lowers the money supply, then nominal income must fall. With less money at the original nominal income, people spend less to try to build up their money holdings.

If prices are flexible, then prices fall immediately with no change in real income, until people only want the amount of money that the Fed has supplied. If prices are sticky, then first real income, output, and employment fall, and then slowly the price level falls instead. (MV=PY. First Y falls, then Y recovers and P falls.)

A graph, except for the opposite case, how higher money growth causes inflation:

People also want to hold less money when interest rates are high. So before income falls, when the Fed lowers the money supply, interest rates rise. People try to borrow money they need, sending rates up. So we see lower money supply with higher interest rates, then a recession, and finally a lower price level. (MV(i) = PY, so higher i and lower V take up the slack before PY move.)

That’s a lovely story. It doesn’t really work as well as I made it sound. There is an unsolved “multiple equilibrium” problem. My story has mechanically sticky prices, but prices are choices, and an economic theory has to describe why and how they are sticky, and why they are sometimes not sticky at all. Also, the “dynamics,” how a basic theory without time in it stretches out over time, don’t work out well, which will be a central problem later.

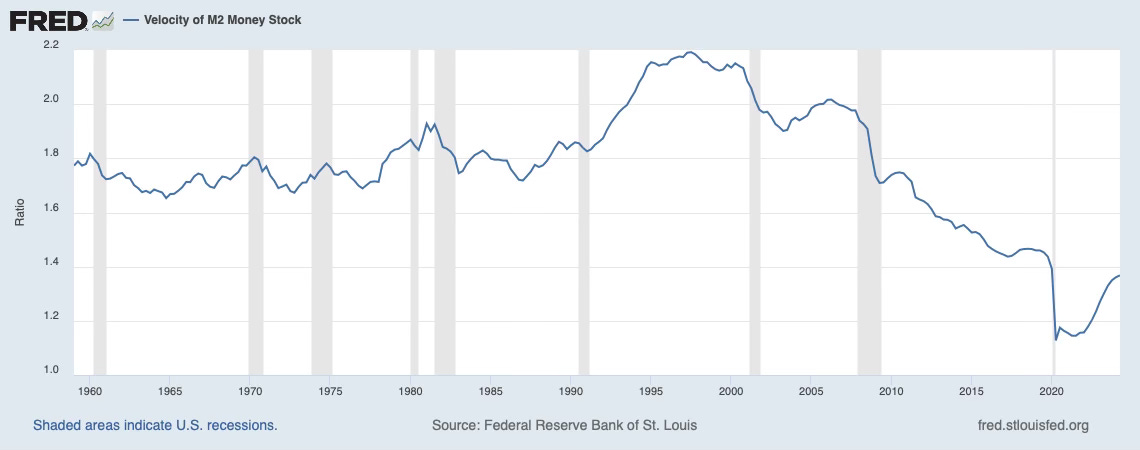

But the bigger problem is that this theory just doesn’t apply to today’s world. The Fed does not control money supply. The Fed sets interest rates. There are no reserve requirements, so “inside money” like checking accounts can expand arbitrarily for a given supply of bank reserves and cash. Banks can create money at will. The Fed still controls the (immense) monetary base (reserves+ cash). The ECB goes further and allows banks to borrow whatever they want against collateral at the fixed rate. The Fed lets banks arbitrarily exchange cash for interest-paying reserves. Most “money” now pays interest, so raising interest rates doesn’t make money more expensive to hold.

Monetarist theory is perfectly clear: The Fed must control the money supply. If it does not do so, and either targets interest rates or provides “an elastic currency” meeting demand, the theory does not work. “Money” and “bonds” must be distinct assets. If money pays the same interest as bonds, or if bonds can be used as money, the theory does not work.

It’s a nice theory. It might be a theory of how the Fed could control inflation, or perhaps how money supply (by the Fed, gold discoveries, etc.) did control inflation in the past, even as recently as the 1980s. It might even be a theory of how the Fed should control inflation. (I’m throwing bones to my many monetarist friends.) But it is not a theory of how the Fed (and the ECB, BOJ, EOE, etc.) does control inflation by raising interest rates without any money supply control.

What about the “stability” of money demand, that money holdings seem to track income? That shows the stability of money demand, not that money supply causes nominal income to change. When nominal income changes, people want more money, yes. But with an interest rate target and no reserve requirements, supply automatically expands to follow demand, not the other way around. Nominal bicycle demand tracks nominal income pretty well. That doesn’t prove that the Fed controls inflation by controlling bicycle supply.

Interest rates with flexible prices

So we need a theory based on interest rate targets, not money. Starting in the 1980s, economists constructed one. But it does not produce anything like the Standard Doctrine.

In place of money demand, we start with the Fisher relationship: The real interest rate is the nominal interest rate less expected inflation. If they charge you 5%, but you expect 3% inflation, you pay 2% in real terms, and act accordingly. Turning that around again, if the Fed raises the nominal interest rate, and the real rate is unaffected (flexible prices), then expected inflation must rise. In equations,

i is the nominal interest rate, r the real interest rate and 𝛑 is inflation. Subscripts indicate time.

How does an interest rate rise affect expected inflation? At the old expected inflation, the higher nominal interest rate is a high real interest rate. That offers an opportunity to save, consume less today, make a good return, and then consume more in the future. When people do that, they lower demand today and raise demand in the future. With flexible prices, output stays the same, so less demand lowers the price level today and pushes up the price level in the future. Expected inflation — future price level over today’s price level — rises, pushing the real rate back to where it was.

The Fisher relation works a lot like the old monetarist story with flexible prices. Higher money growth means higher inflation, immediately. Higher interest rates mean higher inflation, immediately. That’s exactly how a “frictionless” model should work.

Except the sign is wrong relative to the Standard Doctrine we’re trying to chase down. Higher interest rates raise inflation? Are you out of your mind? You won’t get invited back to Jackson Hole if you say that out loud.

Still, it makes a lot of economic sense as a “long run” relationship, just as it makes sense that higher money growth raises inflation in the long run. Countries with large inflation have high interest rates. Over time, interest rates and inflation in the US move together:

Standard current (new-Keynesian) models all predict that higher interest rates lead to higher inflation in the long run, though their authors don’t talk about it a lot. (Everyone likes to go to Jackson Hole?) The Fisher relation is the basic heart of those models.

So it shouldn’t bother us too much if they look at us like we’ve lost our minds. Most Fed people and commenters have only seen a lot of short runs. Common experience doesn’t teach much about long-run what-ifs. They laughed at Friedman when he said money growth raises inflation in the long run. Don’t you know inflation is a “wage price spiral” coming from “cost push” factors, corporate greed, and so on?

And the flexible price story was always an unrealistic starting place. Surely if we add sticky prices or similar realisms we’ll get something like the Standard Doctrine in the short run?

But getting to the Standard Doctrine is harder than it was for money. The money story started with the right sign. Lower money growth produces lower inflation. With sticky prices, lower prices and lower output split the effects of lower money growth for a while. For higher interest rates to lower inflation, however, it is not enough that the real interest rate r and expected inflation split the difference. The higher nominal interest rate must raise the real interest rate more than one for one, so expected inflation can go down. As you can guess, no current model has that sort of extreme effect.

The top left picture shows how interest rates raise inflation with flexible prices. Top right, if the real rate and inflation just split the difference, then sticky prices slow down higher inflation, but they don’t give us lower inflation after interest rates rise. To get higher interest rates to lower inflation, we need the bottom figure, in which somehow the real rate rises more than one for one with the inflation rate. That doesn’t happen.

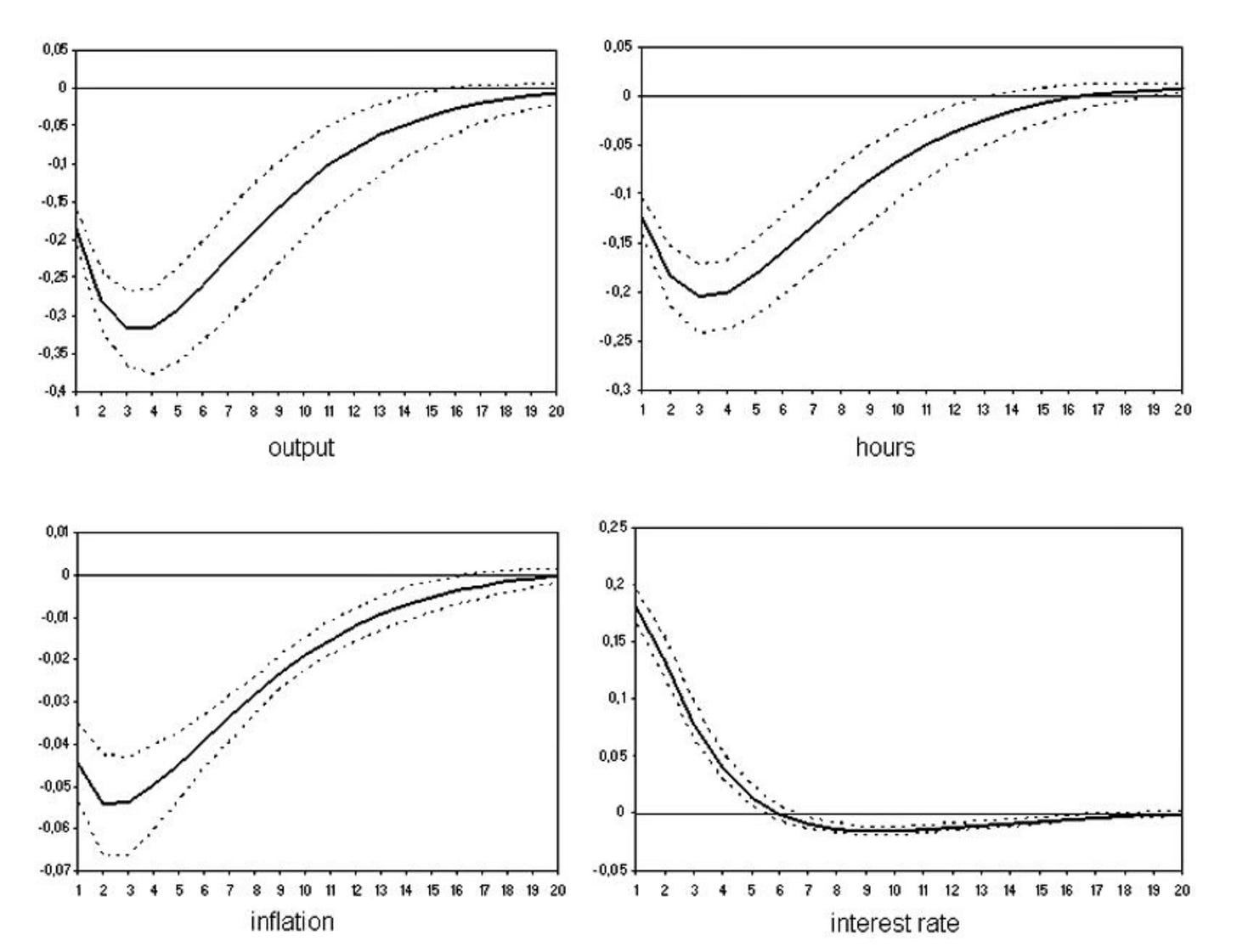

I’m not making this up. Here is the same question posed to the standard new-Keynesian model: What if the interest rate rises, there is no change to fiscal policy, but prices are sticky?

Sensibly, sticky prices slow down the positive response, and split the higher nominal rate between a higher real rate and inflation for a while. But sticky prices do not change the sign. They do not produce a lower inflation either immediately or in the future. They do not produce a real rate that moves more than one for one with the nominal rate. This is a more general truth: sticky prices don’t fundamentally change the story of the frictionless model, they just draw out the dynamics.

Before we add more complications, pause a second and see the larger quest. We start with a simple supply and demand view of the world, in which prices move quickly. To the extent that doesn’t produce the answer we want, we add “frictions,” money, sticky prices and then more. My goal is to ask what are the minimum necessary frictions needed to get the Standard Doctrine. Surely the basic idea is the sort of thing that can be explained to undergraduates, without a lot of institutional detail. Maybe credit constraints and financial frictions, for example, add to the “monetary policy transmission mechanism.” But hopefully that’s an additional channel on top of a basic understandable and robust channel. Hopefully monetary policy doesn’t stop working at all, or change sign, if there are no credit constraints. We’re after that basic story. We will find it isn’t there.

Lowering inflation right away.

Even without sticky prices, we can see the central way current economic models try to get around the wrong-sign problem.

A rise in interest rates must raise expected future inflation, but it can lower the current price level (pt), and hence current inflation (πt=pt-pt-1). Last year’s interest rate controlled expected inflation today (it-1=r+Et-1πt), but not unexpected inflation (πt-Et-1πt).

The left panel of the picture shows a possibility. While the higher interest rate at t means higher expected t+1 inflation, we still could have an unexpected jump down in inflation at time t. Of course, we could also have an unexpected jump up at time t as well.

The Fisher relation is not a complete model of inflation. The many possibilities for unexpected inflation give us some wiggle room. We need to complete the model to choose which happens.

To get inflation today πt to jump down, new-Keynesian theorists assume that in addition to setting the interest rate that we see, the Fed makes a threat: If unexpected inflation doesn’t go where the Fed wants it to go, the Fed will blow up the economy with hyperinflation or hyper deflation. Adding a rule that nature abhors a hyperinflation or deflation, the Fed then “selects” one of the many possible equilibria, one of the many values for unexpected inflation. This additional “equilibrium selection policy” can give us the unexpected disinflation at time t.1

Fiscal theory notices a different and I think (of course) more plausible route to the same result. Unexpected deflation is a present to bondholders, who get paid off in more valuable dollars, from taxpayers. To get an unexpected deflation, the government must raise tax revenue or lower spending to make that gift to bondholders. In equations, unexpected disinflation must equal the change in the present value of primary surpluses,

𝜌 is a number a bit less than one, s represents the real primary surplus (tax revenue - spending, not including interest costs) scaled by debt.

This fiscal condition completes the model: the Fed’s interest rate target sets expected inflation, fiscal policy sets unexpected inflation. To get the decline of inflation in the left hand panel, we pair the interest rate rise with a fiscal contraction.

New-Keynesian models actually work the same way. They assume that after the Fed makes its hyperinflation / deflation threats and selects lower unexpected inflation, the rest of the government “passively” raises taxes or cuts spending to pay the consequent windfall to bondholders. In either case, the lower inflation comes with the tighter fiscal policy.

Obviously, I think the fiscal theory story makes a lot more sense. The Fed does not have an “equilibrium selection policy.” The Fed does not deliberately destabilize the economy. The central story of how interest rates lower inflation is that the Fed threatens to blow up the economy in order to get us to jump to a different equilibrium. If you said that out loud, you wouldn’t get invited back to Jackson Hole either, though equations of papers at Jackson Hole say it all the time. The Fed loudly announces that it will stabilize the economy — that if inflation hits 8%, the Fed will do everything in its power to bring inflation back down, not punish us with hyperinflation.

But we don’t have to take sides on that debate, because the result is the same, and the question here is whether current models can reproduce the Standard Doctrine. When interest rates rise, we can have an instantaneous jump down in inflation, that lasts one period before inflation rises again.

But this is a long way from the Standard Doctrine. First, we still have inflation that jumps down instantly and then rises over time, where the Standard Doctrine wants inflation that slowly declines over time. That sign is still wrong.

Second, the jump occurs because, coincidentally, fiscal policy tightened at the same time. Whether that happened independently, by fiscal-monetary coordination, or because the Fed made an equilibrium-selection threat and Congress went along doesn’t matter. Without the tighter fiscal policy you don’t get the lower inflation. So this is not really the effects of monetary policy. At best it is the effect of a joint monetary and fiscal policy.

Moreover, the fiscal/equilibrium selection business is doing all the work. You can get exactly the same unexpected inflation decline (or rise) with no change in interest rate at all. The right hand panel illustrates. To a new-Keynesian, the Fed simply has to announce its lower target (unexpectedly), and the hyperinflationary threat. Inflation goes down, Congress quickly passes a tax increase, and the price level is restored to (say) its pre pandemic level. It’s a pure “open mouth” operation with no change in interest rate at all. (You can see some new-Keynesian influence in the Fed’s increasing use of talk rather than action.) To a fiscal theorist, Fed talk was irrelevant, but the same tax increase did the same trick. The fiscal shock brought inflation down (or, in 2021, raised it) without the Fed needing to do anything. Indeed raising interest rates hurts the inflation fight, since it raises future inflation.

The mechanism is also a long way from the Standard Doctrine. The decline in inflation has nothing to do with the higher interest rates. There are no higher real interest rates anyway in this story. There is a fall in aggregate demand, but it comes entirely from tighter fiscal policy, having nothing to do with higher interest rates.

Of course, you may say. We need sticky prices or other frictions. That comes next. But first, let me reiterate the point of all this. With monetarism and flexible prices, we start with a model that has the “right” sign: higher money growth raises inflation. With interest rates, we start with a model that has the “wrong” sign: higher interest rates raise inflation. Sticky prices have a lot more work to do. It also means that sticky prices, or whatever we eventually add to get the Standard Doctrine, are necessary to understand the basic sign and operation of monetary policy, in a way they are not for the monetarist story.

Interest rates and inflation with sticky prices

The standard textbook model consists of an “IS” curve that describes how higher interest rates lower output, and “Phillips” curve which describes how lower output or employment translates into inflation. The latter is where we put the idea of sticky prices in the model. The basic problems we found with the flexible prices remain: higher interest rates by themselves raise output growth and inflation, where the Standard Doctrine says higher interest rates reduce both. At best we can get a jump down before the boom, but that depends on equilibrium selection or fiscal austerity.

The full math is harder but you can see the basic intuition (and this observation is the new to me insight that got me to write this long post)

In equations the IS and Phillips curves are

where x is output, i is the interest rate, 𝜋 is inflation and the other greek letters are parameters. These equations leave out constants, like the r in the original Fisher relation.

The “IS” curve says that a higher real interest rate — an interest rate higher than expected inflation — causes people to spend less today xt, save, and then spend more in the future xt+1. That’s the “wrong” sign right there: Higher real interest rates make output higher in the future than today, and so raise output growth. The best we can hope to do is to have output jump down instantly today when the interest rate rises.

The Phillips curve says that inflation today depends on what firms think inflation will be in the future — raise prices now if you know everyone else will raise them tomorrow — and higher still if the economy is booming. This is where “sticky prices” come in. If prices were perfectly flexible inflation would not have any effect on output.

Again the sign is “wrong.” Suppose the economy does soften, lower xt. A softer economy means lower inflation 𝜋t. But it means lower inflation relative to future inflation. It means inflation rises over time. At best, perhaps we can get inflation to jump down immediately, but then inflation still rises over time. We wanted the slower economy to slowly bring future inflation down over time. (This is an old puzzle, pointed out by Larry Ball in 1993.)

We’re right where we were with the simple models. The only way to get inflation and output to decline at all is to pair the interest rate rise with a FTPL fiscal shock or a multiple-equilibrium-selection-threat by the Fed, which induces a fiscal shock. Even then, we still get inflation that jumps down and then rises, and has nothing to do with the mechanism of the Standard Doctrine. The fiscal shock or equilibrium-selection threat is still coincidental with raising interest rates, and indeed has to fight the fact that higher interest rates want to raise inflation.

Economists naturally start to add ingredients, but so far without success in the goal of a simple fully economic model in which in which higher interest rates lower inflation, lower future inflation, without a contemporaneous fiscal tightening. For example, here is the response of the famous Smets and Wouters model to a monetary policy shock

When the interest rate rises, inflation and output jump down immediately. They have a little bit of momentum but quickly turn around and rise after that.

This model also has a fiscal tightening to pay a windfall to bondholders after inflation goes down, so it does not answer the question what can higher rates do on their own. As you see, it works like a drawn out version of the frictionless model.

The literature extending new-Keynesian models is immense, of course. The current emphasis is to add “heterogeneous agents.” But so far none of the thousands of papers I have seen have overcome these basic problems. A few that produce responses that sort of look like the Standard Doctrine do so with dozens of complications, and do not embody anything like the mechanism of that Doctrine, and are not the simple textbook model that one hopes is there somewhere for explaining the basic sign and mechanism of monetary policy.

Here is the best I know how to do. The model is the above standard IS and Phillips curves, plus long term debt. The exercise is a rise in the interest rate with no change in fiscal policy.

Inflation goes down, at least temporarily. But it goes down right away and then rises, unlike the Standard Doctrine. And the mechanism is utterly unlike the Standard Doctrine. It involves promising to inflate long term bonds, which makes short term bonds more valuable.

Interpreting theories

How could this state of affairs have gone on so long, that the basic textbook model produces the opposite sign from what everyone thinks is true, for 30 years? Well, interpreting equations is hard.

Some economists may have fallen into an easy trap. The model produces inflation that jumps down. Well, it’s a simple model, so it’s easy to interpret that “in the real world” as a prediction that inflation will go down slowly over time. You add the long and variable lags as part of the interpretation not as part of the model.

Doing so is common. If you write supply and demand for apartments, and you ask what happens if there is rent control, the simple model says available apartments go down. Well, we know that takes time, and we sort of figure we could add the time lags if we wanted to, so we interpret the simple supply and demand jump to mean apartments go down with long and variable lags.

That’s how Milton Friedman thought in the 1960s. When Milton Friedman said that money causes inflation with “long and variable lags,” he was referring to his historical analysis, not dynamic economic theory. He happily applied a basically static model to a dynamic situations. One of the big changes in economic theory since about 1972 is that we take time seriously. The economic theory has to start with how people think about decisions today vs. the future. It has to describe how prices evolve over time. We can’t just say that more money raises inflation, then wave our hands that prices are sticky and say it will take some time.

The equations I wrote down and the logic behind them are about how people behave trading off now vs. the future. They describe how prices evolve over time. You absolutely may not take a jump (xt and 𝜋t) today and use it as a parable for how variables move slowly over time.

I think there is some wishful thinking as well. New Keynesian models were developed by academics who wanted a theory of inflation under interest rate targets, thought the Standard Doctrine about right, and wanted to put serious economics in place of the mechanical ISLM framework that seemed to replicate the Standard Doctrine. (Below). It was natural not to notice that the equations said something very different from what the researchers were looking for.

Non-economic theories

One reaction to this grand failure has been for many “freshwater” types to simply declare everything since 1970 a big mistake. Just go back to ISLM from 1960s and 1970s undergraduate textbooks. Alan Blinder’s Monetary and Fiscal History is basically a book-length version of this argument, also made loudly by Paul Krugman. Lots of policy analysis basically takes this approach without saying so explicitly.

In the context of my little equations, they either throw out the t+1 terms, or turn them into t-1 terms.

The first approach is simply to return to what we might call “static” Keynesianism. Static means there is no time in the model. Each date works on its own with no future and no past. The higher interest rate lowers spending today, period, and lower output lowers the price level today, period. We could write that in equations as

Here I wrote the same model as before, but leaving out future output in the first equation, and treating expectations as fixed numbers, or a third independent force, but not connected to what the model says will happen next year. You can solve it easily for

Higher interest rates lower inflation. In this model, right away. People then add long and variable lags by waving hands, as Friedman did.

Another approach to the Standard Doctrine is to assert that expected inflation is formed by experience with past inflation, not looking forward. In equations,

You can solve that one too for

Higher interest rates do lower inflation. Moreover, inflation is now unstable, since the coefficient on previous inflation is greater than one. Inflation or deflation will spiral away at peg or the zero bound. A higher interest rate today sets off such a spiral so it does lower inflation even more in the future.

To fully capture the Standard Doctrine, add a Taylor rule, by which the Fed raises interest rates more than one for one with inflation, plus a monetary policy shock:

Plugging that in,

By moving interest rates more than one for one with inflation, the Fed stabilizes an otherwise unstable economy. The Fed’s job is like a seal balancing a ball on its nose: it must move quickly, more than one for one and preemptively to keep the ball from spiraling away. Positive monetary policy shocks u still bring down inflation.

Here is a simulation from this model, with the Taylor rule.

The Fed raises interest rates with a disturbance u to the Taylor rule. Higher interest rates are higher real rates, because expectations don’t move. The higher real rate lowers output, that lowers future inflation through the backward-looking Phillips curve. Inflation heads down. But before a spiral can take off, the Fed follows inflation down with lower rates, and carefully pulls back on the stick for a soft landing at lower inflation.

This simulation not only embodies the prediction of the Standard Doctrine, it embodies the mechanism of the standard doctrine. Higher interest rates lower output, lower output lowers inflation, and all with a lag. The Taylor rule stabilizes an otherwise unstable economy. All with textbook simplicity. This is the standard story told of the 1980s. (It includes a big recession, low x, not shown.)

Hooray, you might say. But this is not the answer we are looking for. First, we are looking for an economic theory. What we have here is just a system of mechanical equations that repeats the Standard Doctrine in mathematical form. Why do higher real interest rates lower output? Why does lower output lower inflation? Why do people mechanically extrapolate the past to think about the future? In this view, someone possessing the deep secret of this model can do a lot better than people in the model of figuring out what’s going to happen. But central bankers haven’t been doing a great job of forecasting inflation either. Sure, imperfect expectations are a useful ingredient for matching some dynamics and episodes a useful addition to a basic model that works. But here they are a minimal necessary ingredient to deliver the basic sign and stability of monetary policy. If people ever catch on, it’s game over. If this is our simplest model, we have to say there is no economic theory underlying the Standard Doctrine of monetary policy.

Second, even this model requires both fiscal and monetary policy. Notice the long period of interest rates above inflation. During that period, interest costs on the debt rise, and also people who held bonds before the disinflation got paid off in more valuable dollars. Both require a fiscal contraction. This is a plot of a joint monetary-fiscal stabilization, not monetary policy alone. In “Expectations and the neutrality of interest rates” I show that even in this model, higher interest rates without a fiscal policy tightening cannot lower inflation at all.

Where we are

To reiterate, there is no simple textbook economic model in which higher interest rates lower inflation slowly over time, without contemporaneous fiscal tightening. The consensus economic theory produces the “wrong” sign relative to the consensus belief of the policy world.

Maybe the beliefs of the policy world are wrong and the model is right. Maybe the model is wrong and the experience of the policy world is right. Empirical work is just as inconclusive, but that’s for another post.

The ingredients of this standard textbook model are also known not to be reliable. It’s hard to see evidence in the data that higher real interest rates correlate with greater consumption or output growth. The Phillips curve is even more of a mess, basically just a cloud of points. It’s theoretically a mess as well.

Implications and motivations

I respond in part, with some delay, to Scott Sumner, “Is Macro Making Progress?” (No, according to Scott), and “The Federal Reserve’s Little Secret” in the Atlantic by Rogé Karma. I put together some of these thoughts from the 2024 MFR Program Summer Session for Young Scholars where it was my job to talk about great new opportunities.

Karma has it right

No one really knows how interest rates work, or even whether they work at all—not the experts who study them, the investors who track them, or the officials who set them.

He goes on to explain well how interest rates are supposed to create a recession which through Phillips curve lowers inflation. Except there was no recession.

Scott bemoans

I was asked to name the most important paper published in my field (which is macroeconomics) over the past ten years. I couldn’t think of any.

I have a suggestion for Scott, but I think I’ve plugged fiscal theory enough.

They are right, I think, about the state of affairs, but they are wrong about its implications. There is a consensus theory of monetary policy, that has utterly dominated academic work since about 1990 — the “new Keynesian” model. The basic framework hasn’t changed much. Academic work has extended that framework with many additional complications. But there are now clearly gaping holes in its foundations, elephants in the room about its failure to describe facts, and a deep divergence between its predictions and the Standard Doctrine.

That is the most exciting time for a field! The existing paradigm is crumbling. The policy world follows a consensus doctrine with no respectable economic foundations. Basic issues are up for grabs: Do higher interest rates lower inflation? How? When? With what preconditions (like, fiscal policy)? Is an interest rate peg possible? How much of inflation is under the Fed’s control anyway? What frictions underlie monetary policy? Do we need money, credit, financial frictions to get off the ground? This is physics 1904. This is a moment in which very simple basic thinking and basic matching theories to facts has the potential to revolutionize our understanding. This should be a great time to be a young macroeconomist!

Karma’s essay, by the way, while great on current lack of knowledge, falls apart right at this juncture in the last paragraph

Fortunately, there are many other ideas for how to fight inflation. They include taxing the consumption of the rich to restrain spending, boosting immigration to alleviate worker shortages, cracking down on price-fixing, and keeping strategic reserves of important goods in case of a supply crunch.

The first idea shows what happens when you let your politics infect economics. Taxes can lower aggregate demand, but the rich notoriously don’t spend much. They sit on their Tesla stock. The rest of the ideas make the most common mistake that pervades inflation discussions: they mistake relative prices for the price level. All of those are reasons that one price would go up relative to another but not why all prices would go up. Inflation is about a decline in the value of the currency, not about rises in individual prices.

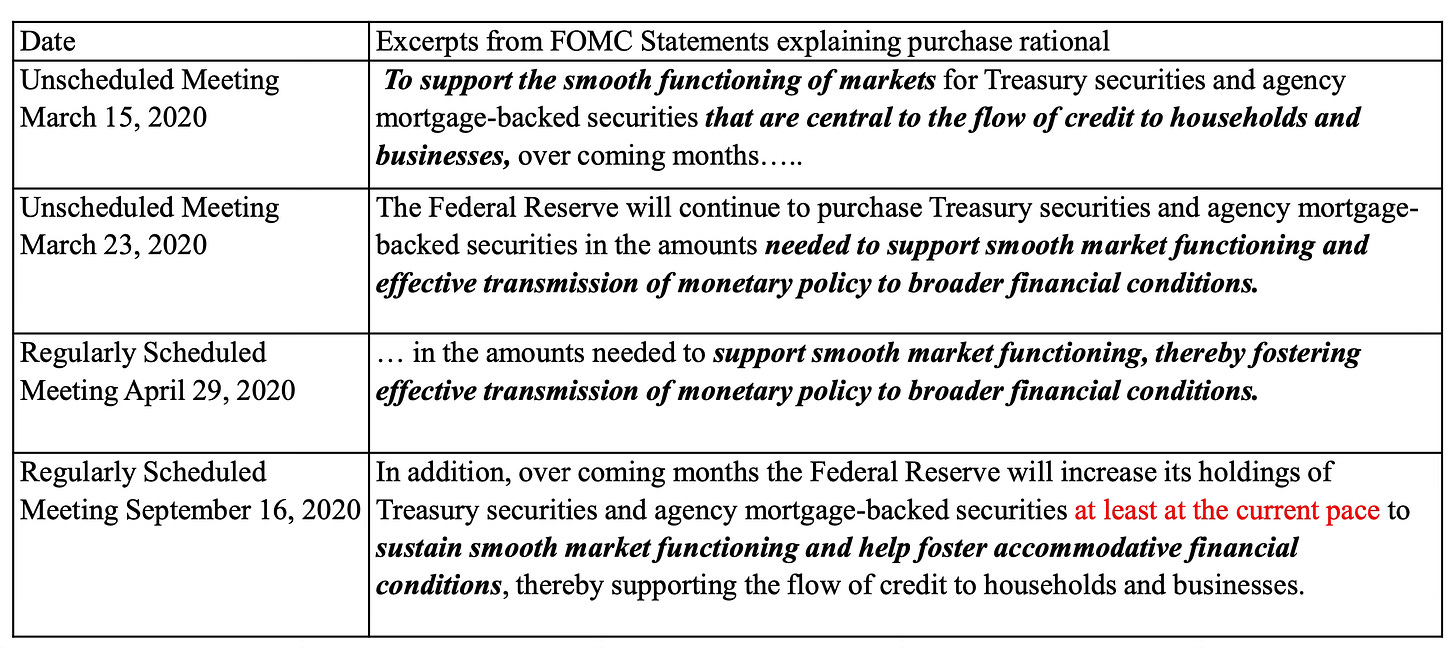

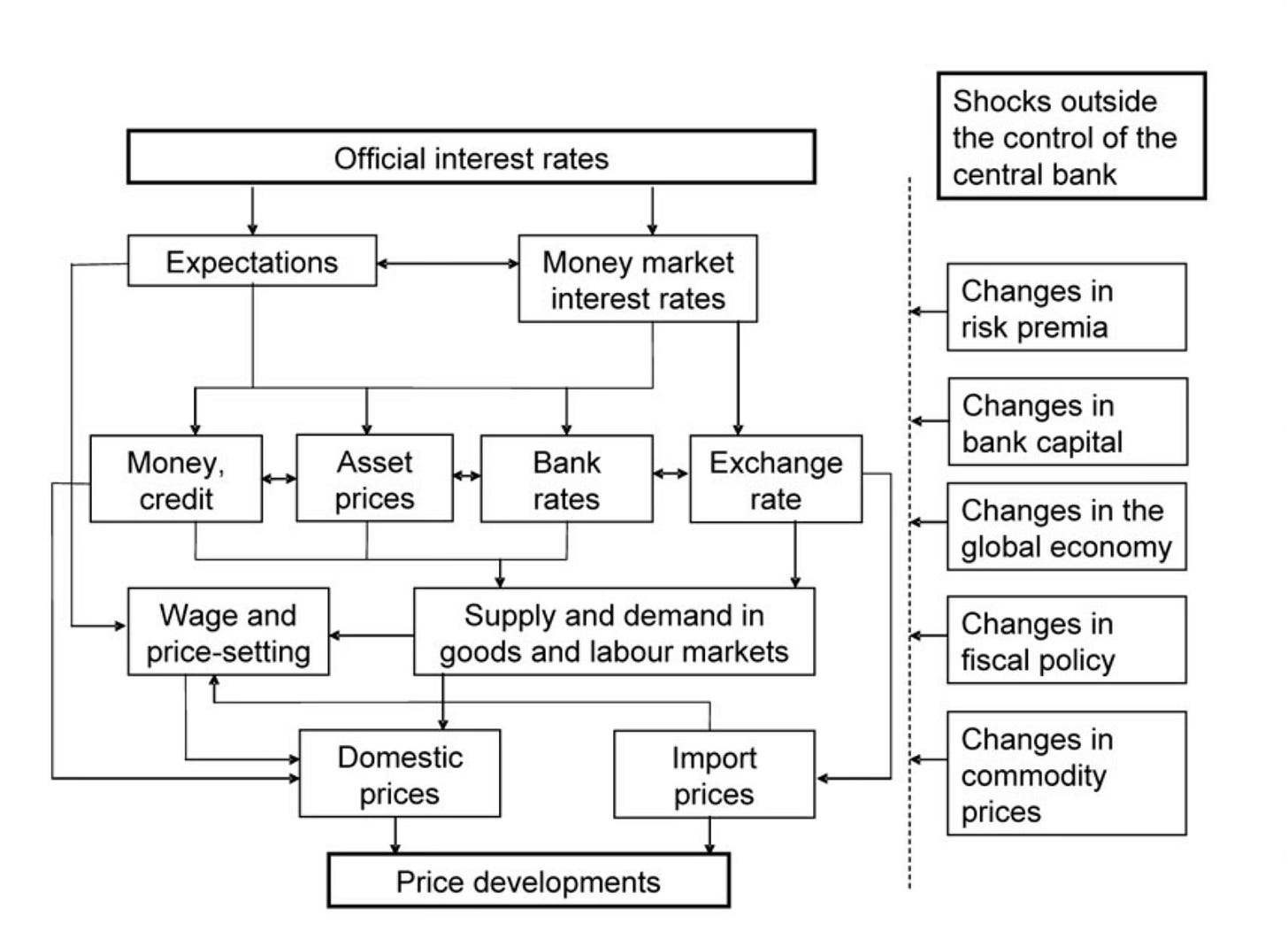

I am also motivated by how much “Monetary Policy Transmission” is a new central bank buzzword. The Fed’s Jackson Hole conference was half about “monetary policy transmission,” with four sessions on the subject. The ECB has been using the “transmission” buzzword for a decade.

“Transmission” assumes there is a basic economic story of how higher interest rates lower output and then inflation, and then goes on to talk about more complicated channels of this “transmission.” A lot refers to the idea that central bank interventions in bond markets are important not for trying to influence bond prices directly, as was the case in QE, but to maintain “transmission” of monetary policy when asset markets are “dysfunctional.” Here the ECB is ahead of the US. Back in 2010,

The Governing Council of the European Central Bank (ECB) decided on several measures to address the severe tensions in certain market segments which are hampering the monetary policy transmission mechanism and thereby the effective conduct of monetary policy oriented towards price stability in the medium term. The measures will not affect the stance of monetary policy. …1. … interventions in the euro area public and private debt securities markets (Securities Markets Programme) to ensure depth and liquidity in those market segments which are dysfunctional.

Announcing the “transmission protection instrument” — a very loosely constrained bond buying program — in 2022,

…the TPI is necessary to support the effective transmission of monetary policy.

The TPI … can be activated to counter unwarranted, disorderly market dynamics that pose a serious threat to the transmission of monetary policy across the euro area….

…the Eurosystem will be able to make secondary market purchases of securities issued in jurisdictions experiencing a deterioration in financing conditions not warranted by country-specific fundamentals, to counter risks to the transmission mechanism.

In his presentation at Jackson Hole, “Financial Markets and the Transmission of Monetary Policy,” and advocating that the Fed become (or become more) a “market maker of last resort,” Anil Kashyap documented the Fed taking up this idea.

In half of these quotes, the Fed is adding “smooth functioning of markets” as a new mandate. But in the other half, the Fed justifies intervention as supporting “transmission” of monetary policy. The ECB is careful in many statements to justify its interventions as only aiming at “transmission” of monetary policy, and that to its price level objective only. (Much more in the euro book draft.)

What does bond market “dysfunction” mean? Why is it important for “monetary policy transmission?” Again, all of this might make sense if we had a basic understanding of “transmission” and are looking for new channels. But we don’t.

As a humorous example of technocratic hubris, the ECB has an explainer on monetary policy transmission, with the following lovely graph.

Apparently they really think they have scientifically valid understanding of this Rube-Goldberg contraption, together with the technocratic capacity to direct all the arrows, should they become “dysfunctional.”

A last thought: Throughout all of macroeconomics, the economic damage of recessions comes entirely because prices are sticky. If prices were flexible, monetary policy would result in costless inflation, instantly, and no unemployment. Economists and central bankers take “stickiness” as given and go on to advocate complex policies that take advantage of them. But if sticky prices are the key economic problem causing all the pain of recessions, why does essentially nobody advocate policies to unstick prices? Instead we have intervention after intervention to make prices more sticky: price controls, rent controls, union support, and so on. Similarly, if bond markets are routinely “dysfunctional,” should we not figure out why and fix them, rather than use this as an excuse for central banks to go on a shopping spree?

The next post, “Do Higher Interest Rates Raise the Exchange Rate?” takes the same analysis to that classic question, with much the same result.

Equations: The Fed has a stochastic inflation target π*t. To get actual inflation to equal this target, the Fed sets the interest rate target

Then the Fed threatens that the actual interest rate will respond aggressively to any deviation from the inflation target,

With 𝜙>1, the Fed says that inflation comes out higher than the target, it will raise interest rates more than one for one, so that next period’s inflation is higher still. The Fed will induce a hyperinflation. Remember it = r+Etπt+1. Adding that and the definition of i*t , inflation follows

With 𝜙>1, any inflation leads to hyperinflation. Ruling out hyperinflation we conclude πt = π*t. Notice we never observe the threat to hyperinflate.

Thanks for this article.

Four comments from a non academic economist who once wanted to work in a Central Bank Monetary Policy department but was fortunate enough early on to realise that nobody could understand how it all works:

1. I see problems in the Measurement of Actual Inflation as a key impediment in understanding how inflation works. For Actual inflation the Laspeyeres vs Paasche question. You have the question how to include housing costs how to calculate hedonic adjustments.

2. In many of the theories the variable that matters is expected inflation, it has its own measurement problems.

3. About the typical error of relative prices vs general price level-> Recent Covid experience highlighted the role of savings in budget constrait -> Yes there is always a budget contraint, but if consumers have savings we have to extend the period of analysis to include the extinguishment of the savings. . With Zero savings/borrowing any supply driven inflation would lead to a relative price adjustment in the given income period. Is it possible that what seems as a general price level increase is in fact a multi-year relative price level adjustment?

4. Nominal illusion: Doesn't the nominal illusion address a lot of failings of the standard theory? i.e. yes real interest rates are unchanged but my behavior is driven by the nominal so interest rate targeting works

I find it strange that in your discussion of inflation you never mention the supply (and demand) for money. Most central banks see their policy rate as the instrument for controlling M (setting it above or below the neutral rate reduces or increases the supply of base money).