Inflation vs. Prices

Did “supply shocks” or “relative demand shocks” cause the recent inflation? Will tariffs raise inflation? Will deregulation and AI, by lowering costs, lower inflation? No.

Don’t confuse the price level with the inflation rate. Don’t confuse relative prices with the price level. These ought to be the first lessons of macroeconomics. But many economists, and most politicians and commenters get them wrong.

“Supply” and “relative demand” shocks are the leading culprits (or dog-ate-my-homework excuses) for the recent inflation. If the pandemic makes it hard to produce or import goods, like TVs, then those goods prices rise. If people stuck at home shift from restaurants and bars to buying Peletons, the price of Peletons go up.

But these forces only raise TV and Peloton prices relative to other prices. If there are not enough TVs to go around, TV prices must rise relative to wages or food. But that doesn’t explain why TV prices go up rather than food prices going down. It really doesn’t explain why all prices and wages go up.

“Monopoly,” “greed,” and “price-gouging,” inflation fallacies for many other reasons, also confuse relative prices with the price level. Greedy price-gouging monopolists raise their prices relative to costs and other prices. That doesn’t explain why all prices rise.

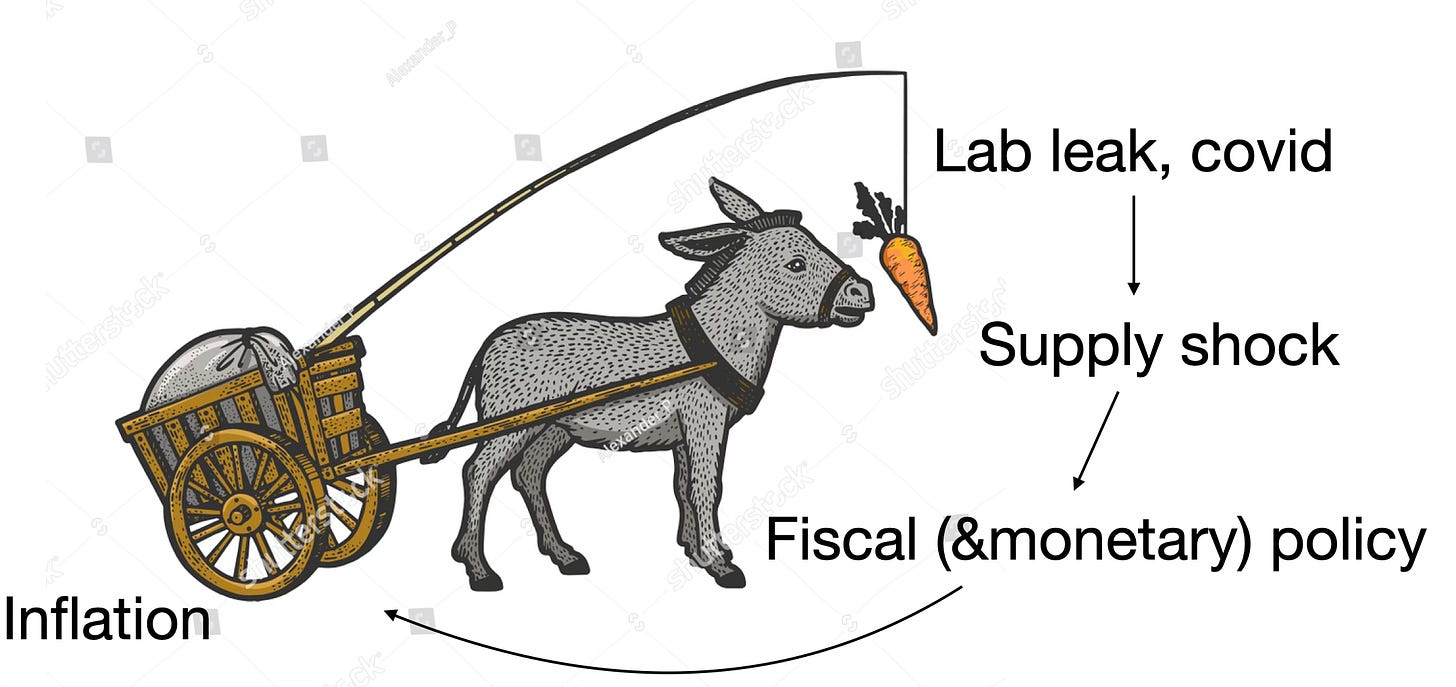

Here’s the standard picture of the supply shock, when (say) you can’t get chips to make TVs. The price level averages the price of TVs and other goods. Inflation goes up.

But you see the two big problems with this story.

First, if the price of TVs goes up and the price of everything else stays the same, how do we have enough money to buy more of everything? Obviously, (and very loosely speaking) someone has to give us more money to be able to pay the higher prices for TVs and the same price for everything else.

A supply shock only causes overall inflation if monetary and fiscal policy respond to the supply shock by increasing demand. That is often considered a good thing to do, because most central bankers think prices going down are worse than prices going up. But it is a choice, and inflation only happens when they make that choice.

(I am speaking loosely here. If the elasticity of demand is one, then prices go up, quantity goes down, and expenditure is the same. But nominal GDP did go up. The larger point is more general: forces that change relative prices do not raise the overall price level unless they induce a monetary or fiscal policy response.)

If you look hard at papers that estimate supply vs. demand shocks and inflation (for example the very nice Smets and Wouters 2024) you will see either increased money supply or an unbacked fiscal expansion providing the demand.

Yes, the price of other things might be sticky downward. But we still need the money to buy things at the higher prices. And downward stickiness does not explain why the price of other things rose, just not as fast.

We understood this in the 1970s. The standard economist response to “oil prices caused inflation” was to make something like the above picture and say that oil price shocks induced monetary policy to stoke demand, and that caused inflation. We seem to have forgotten this lesson.

Inflation is not the sum of (relative) price rises. Inflation is the component of all prices that rise together, leaving relative prices unchanged.

The fallacy of confusing relative prices with inflation has been with us forever. Emperor Diocletian went after price-gougers. Presidents Hoover and Roosevelt fought deflation by encouraging cartelization of industries and labor, so that everyone can raise prices. They did not understand that you can’t raise the overall price level by raising everyone’s relative price. All the children can’t be above average.

Econometric and model estimates look for what shock “caused” inflation. There is a sense in which the supply shock “caused” the inflation. The supply shock caused the government to go on a fiscal spending binge, and the Fed to monetize 2/3 of it, which in turn caused the inflation. But the supply shock was caused by the pandemic. And the pandemic was caused (most likely) by a lab leak. So, we would just as easily say that the lab leak caused inflation.

But all of this causal attribution hides the central economic mechanism. Saying the supply shock caused inflation hides it also, and hides behind the fallacy shown above.

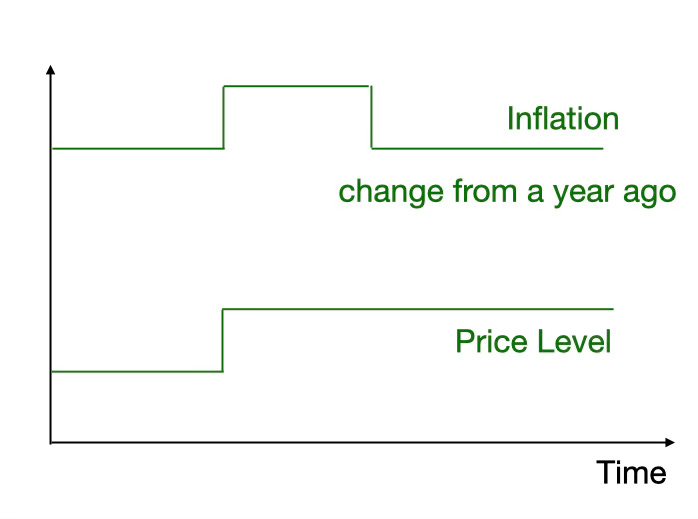

Going back to the first picture, there should be a bout of deflation once the supply shock ends and the level of prices goes back to normal. A supply shock can make sense of a transitory price rise, but not a transitory inflation that leaves all prices permanently higher. The “supply shock” story confuses inflation with the price level as well as confusing relative prices with the price level. All of the relative price stories have the same fault.

Much of the confusion comes from leaving out a nominal anchor. In any economic system there is some force that sets the overall level of prices. In monetarism, it is the supply of money. In fiscal theory, it is the value of government debt. If you don’t move the nominal anchor, a relative price rise cannot raise the overall price level. (Update: important typo fixed in the last sentence!)

You can raise Jimmy relative to Suzy. Or you can Raise Suzy relative to Jimmy. But you can’t raise both of them by pushing one of them up. Only by moving the fulcrum up can you move both of them. The fulcrum is the nominal anchor. Inflation is a movement in the nominal anchor.

Tariffs

Will Trump’s tariffs raise inflation? Here we go again. A tariff is a tax on imported goods. It most likely is passed on to consumers. So, yes, the price of imported goods will go up, as will the price of goods that use imported parts or imported tools. But they will go up relative to other prices. Maybe the other prices go down! The exchange rate may rise so that even the import prices don’t rise. Again, loosely speaking, unless we have the extra money to pay higher prices, unless extra monetary and fiscal policy stimulus moves the nominal anchor, as many prices go down as prices that go up, and the price level does not change.

Even if tariffs raise the price level, that does not lead to a persistent rise in the inflation rate. Instead, inflation rises for one year, and then comes back down again.

(David Andolfatto makes this point recently on x with the example of Japanese taxes.)

Tariffs actually can contribute a tiny bit to lowering inflation. Tariffs raise a little bit of revenue. To the extent that the government doesn’t spend more, and to the extent that the tariffs don’t reduce income too much — to the extent that we are on the left of the long-run Laffer curve for tariffs — the extra revenue helps to pay debt and avoid inflation.

It is curious that many economists who bemoan Trump’s tariffs for their inflationary effect also want to raise corporate taxes. Corporate taxes are also passed along to consumers though higher prices. If tariffs raise inflation, so do corporate taxes! And if the revenue from corporate taxes (if there is any, after long-run Laffer effects) lowers inflation, so does the revenue from tariffs.

Sales taxes are paid by the seller. Yet everyone understands that sales taxes are passed along entirely to consumers in the form of higher prices. That tariffs work the same way should not be too hard to understand.

Tariffs are a terrible economic policy for lots of reasons. But not because they cause inflation.

Productivity, AI, Deregulation

On the other side of the coin, productivity, AI, deregulation, and the new DOGE might make lots of goods cheaper. Will that lead to less inflation? Again, inflation is not about prices, it’s about the value of money. Those goods will be cheaper than others, but the overall level of prices depends on the nominal anchor, fiscal and monetary policy.

More productivity and more real economic growth will lead to more tax revenue, less need for spending, and thus less fiscal pressure for inflation. But they won’t lower prices directly.

Deregulation and pro growth reforms are great economic policy for lots of reasons. But not because they will directly lower prices and thus lower inflation.

Tariffs have absolutely nothing to do with inflation.

Inflation is the effect of the loss of the store of value of money

Monetary policy has an impact on the short-term value of money.

But fiscal policy and it's anticipated impact on Sovereign debt is the determinant variable of the medium and long term value of money

Tariffs are an impediment on the operations of the economy that produces goods and services

Money is a piece of paper

I don’t think I disagree with any of this as a matter of economics, but it seems to miss the politically salient point. If you define inflation (correctly as a matter of economics) as the rate of change of the overall price level that can occur only because of a change in the nominal anchor, then of course a tax like a tariff that doesn’t change the nominal anchor isn’t going to change inflation.

But what we learned from the last election is that as a matter of politics, people didn’t care about inflation defined that way. At the time of the election, inflation defined that rate was down and real wages have been rising. The CPI from September 2023 to September 2034 rose only 2.4%. But people were still angry because what they cared about was not the rate of change of an abstract level of “overall prices” but rather the absolute price level for consumer goods. And every time they walked into a grocery or restaurant and saw prices that were significantly higher than 4 years ago, it made them angry. That’s what voters classified as “inflation.”

So if we impose news taxes like tariffs on imported goods (which include a large share of what people consume today and for which there often aren’t readily available domestic substitutes), that will create a long-lasting increase in the relative price level of consumer goods—i.e., inflation as voters define it. Good luck with the political repercussions of that.