Inflation, Monetary and Fiscal Policy, and Japan, part 2: Fiscal Theory Review

(This is part 2 of a longer essay. The whole thing pdf here if you prefer. The fiscal theory review will be familiar to dedicated blog readers, but I leave it here and in the essay to keep them self contained. If you've seen the fiscal theory review, skip to the next post to get to the novel part about Japan.)

2. Inflation and Fiscal Theory

My main task is to apply fiscal theory of the price level. I'll start by explaining how it neatly describes US experience, and then consider how Japan might fit as well.1

The fiscal theory of the price level states simply that prices adjust so that the real value of debt equals the present value of primary surpluses.

or, linearized

where Where B is debt, P is price level, R is real return, s is real primary surplus, v is the log real value of debt, rho is a constant of linearization a bit below one, ~s is the surplus scaled by the steady state real value of debt, and r is the log return.

It’s just asset pricing applied to the government. Inflation results when there is more debt than people think the government can or will repay by a long stream of primary surpluses, less interest costs.

The asset pricing analogy quickly dissipates common criticisms. No, surpluses need not be “exogenous,” anymore than coupons and dividends are “exogenous.” No, this is not an “intertemporal budget constraint,” any more than Tesla must by budget constraint raise dividends if a bubble sends up its stock price.

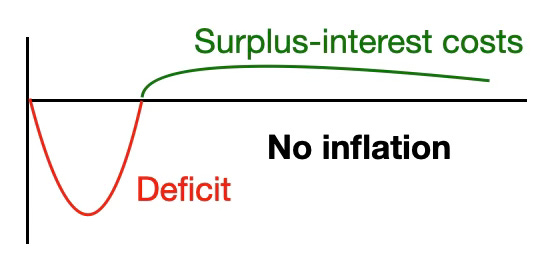

As you can quickly see, fiscal theory does not imply a mechanical relationship between debt or deficits and inflation. Normal, responsible fiscal policy consists of borrowing in bad times, followed by repayment in good times, with no change to the present value of surpluses. We expect to see governments frequently run big debts and deficits with no inflation at all.

Inflation only comes when people believe part of an addition to debt will not be repaid. They try to get rid of nominal debt. The only way to do so is to try to buy goods and services until the price level rises to inflate away sufficient debt.

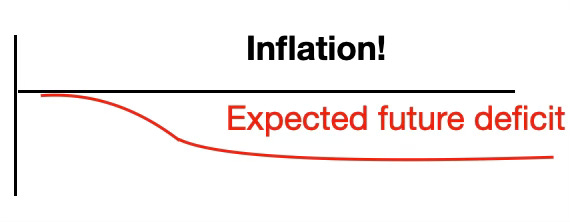

Inflation can come, seemingly out of nowhere, as it often does, with no debt or deficit, if people lose faith in the government.

I do not envision that people sit around the kitchen table making forecasts of government finances 30 years in the future. Inflation results from debt without faith in the fundamental soundness of institutions, that the government will get around to paying off debt sooner or later.

There is no magic debt / GDP ratio past which debt is “unsustainable” and inflation breaks out. Countries that can pledge responsible structural fiscal policies can borrow a lot, and pay it off over decades. Countries that cannot have experienced debt crises with very little debt/GDP.

The present value also highlights that discount rates, equivalently interest costs on the debt matter. The linearized version of the present value formula makes this implication stark. Interest costs enter symmetrically with surpluses. One percentage point of interest costs is the same as one percentage point of deficit to debt ratio. (We can also view debt as an undercounted present value of the total surplus, including interest costs.)

The analogy to asset pricing should also help us to avoid repeating 50 years of hard-won understanding. You cannot prove that price is not the present value of dividends by noticing that Tesla’s price is a lot higher than forecasts of its earnings would seem to justify. Absent arbitrage there exists a discount factor such that, etc., and agents have more information than we do. You cannot prove that debt is not the present value of surpluses just by noticing that Japan’s debt to GDP ratio is pretty high.

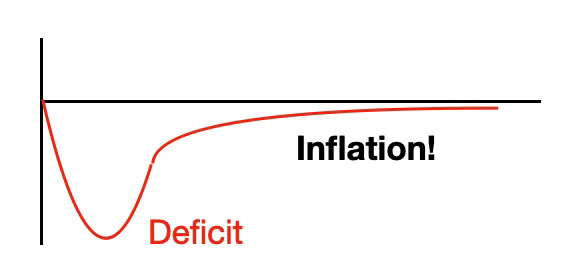

Now, consider what happens when the government suddenly gives people $5 trillion dollars of money or debt, 30 percent of outstanding debt, but only has credible plans to pay back about half that amount. I call that decline in present value of surpluses a “fiscal shock.” In this simple slide the theory predicts that prices jump up 15%.

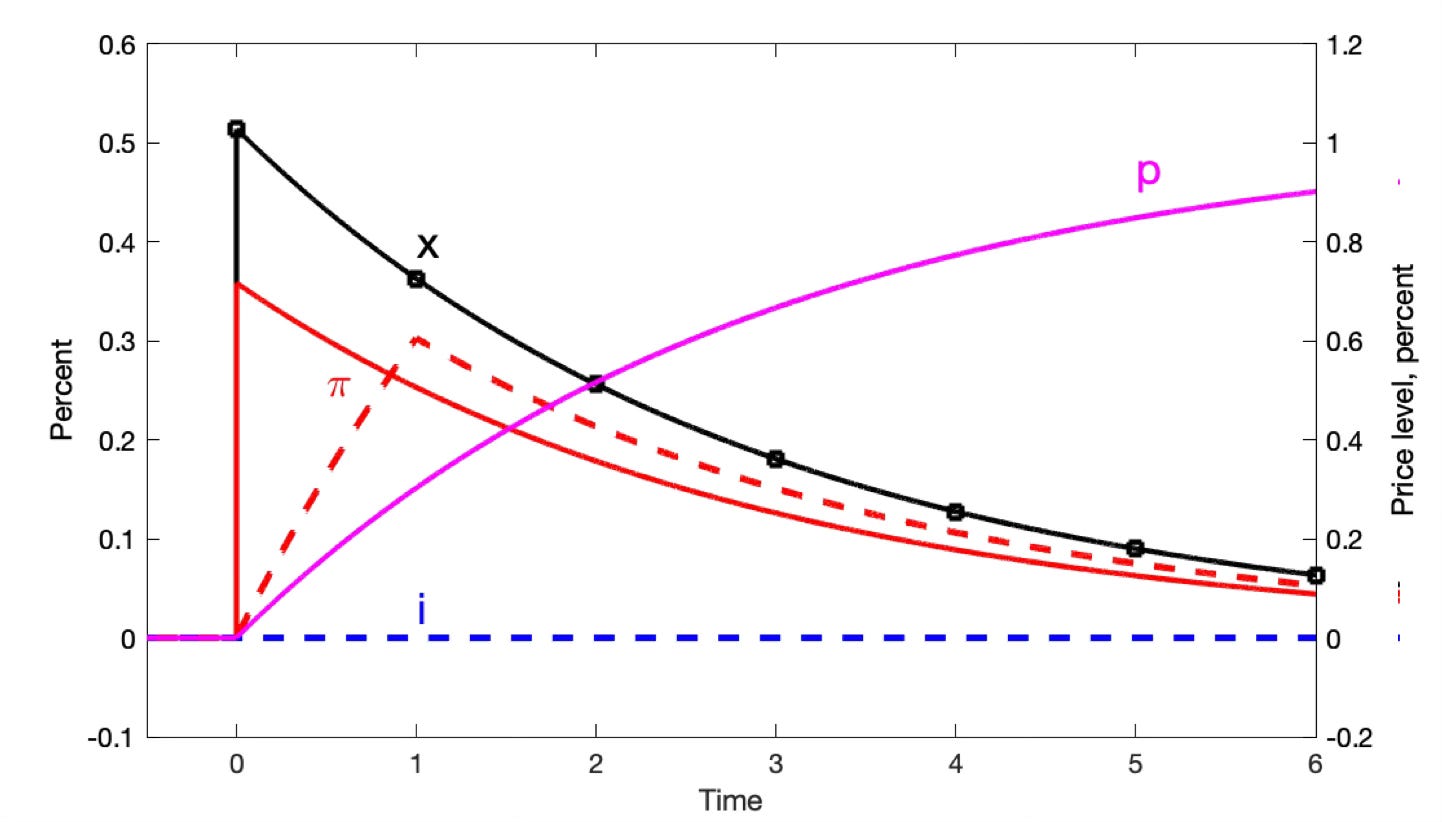

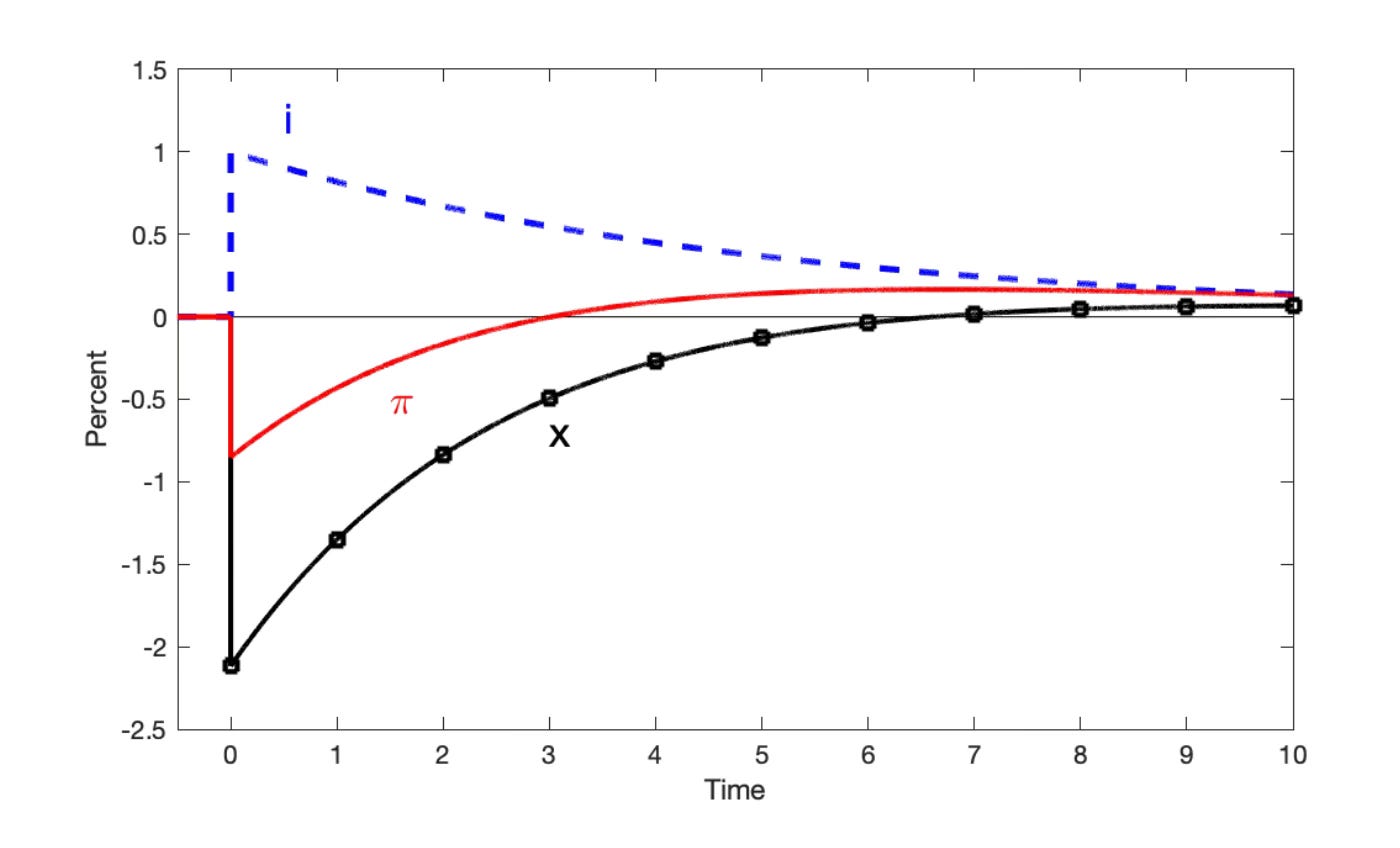

But we know prices are sticky. So let’s turn to fiscal theory with sticky prices. I just add fiscal theory to a totally standard new-Keynesian model. I give the model a fiscal shock, and suppose the central bank leaves interest rates alone.

(The model is, in standard notation

The plot is the response to a 1% decline in surplus.)

Rather than a sudden price level jump, we get a slow price level rise. Inflation jumps up, then slowly declines. Bondholders lose money from a long period of low real rates, interest rates below inflation, rather than from an overnight price-level jump.

In reality, inflation often builds slowly rather than jump upward. In most events, there are several shocks. The extent of the fiscal shock only became known slowly through time. We also measure inflation year over year, as shown in the dashed line, which gives an apparent slow rise in inflation. And of course this is a very simplified model, without habits, capital, and adjustment costs, all of which draw out responses.

Inflation goes away all on its own here, with no high interest rates and no recession. There was a one time fiscal shock. Once sufficient debt has been inflated away, there is no need for more inflation.

Next, what if the central bank wakes up and raises interest rates? I present the results of such a monetary policy shock. (This model includes long-term debt.) Crucially, here I do not assume any contemporaneous fiscal shock. Surpluses stay constant. This is what the central bank can do on its own. Almost all current models pair a fiscal tightening, some of the last graph upside down, with a monetary tightening. They assume at a minimum that fiscal authorities raise taxes to pay extra interest costs on the debt. I ask here what central banks can do on their own without such help, which may not be forthcoming.

Higher interest rates lower inflation and output. However, they raise inflation in the long run. A form of “unpleasant arithmetic” holds here, and quite generally. The central bank can only move inflation around over time. This is a pretty normal-looking plot. Nobody would notice the slight long-run rise as something else would have happened by then. But the mechanism is utterly different from standard central bank doctrine, that higher rates depress aggregate demand and through a Phillips curve depress inflation.

In the fiscal theory model, it is a great and good thing for the central bank to react to inflation in this way. By raising interest rates in response to the fiscal shock, the central bank smooths the inevitable inflation over time. Since output depends on inflation relative to future inflation, that smoothing reduces output volatility. A Taylor rule, with a coefficient just below one, is a very robust policy. The Taylor rule seems to always be the answer, even as the questions change. It brings stability to old-Keynesian models, determinacy to new-Keynesian models, and low volatility to fiscal theory models.

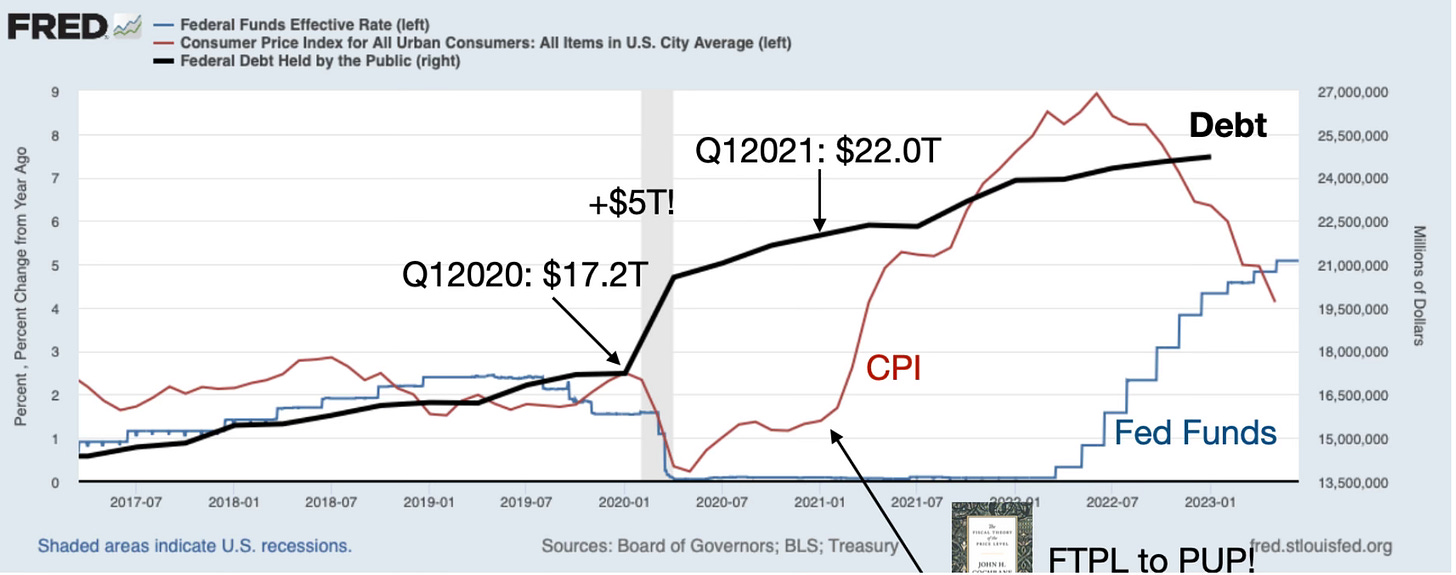

Having seen these graphs, you know how I’m going to interpret recent US history. Our government did indeed send people $5 trillion of money with no clear plans to pay it back. Inflation promptly surged, seemingly out of nowhere, just like the simulation.

Conventional theory says that once inflation is 8 percentage points above interest rates, inflation will spiral upward until interest rates substantially exceed inflation, and drive it back down with a 1980s style recession. Fiscal theory says inflation would go away on its own, absent new fiscal shocks. Inflation goes away a bit faster if central banks react, though a the cost of a slightly more persistent inflation. That also seems to be just where we are.

It’s not that easy of course. Why this time and not 2008? One has to do a historical analysis to believe that it is at least plausible that this time people did not expect about half that debt to be repaid by surpluses or lower interest costs, and last time they did. My papers include that narrative, but in the interests of time I won’t repeat it here. This narrative is not proof, but that fiscal theory has even a plausible story, one so simple, and one that gets the quantities right for both the rise and fall of inflation, is pretty novel.

This inflation surge has huge implications for economics and economic policy, which have not been digested yet. For 13 years in the US and EU and 30 in Japan the policy consensus focused on “inadequate demand,” “secular stagnation,” the idea that we just needed more stimulus to get the economy moving. Borrow or print a few trillion dollars of money, they said, spread it around and prosperity will follow. In the same period, with ultra-low interest rates, large deficits, and low inflation, “r<g”, Modern Monetary Theory and other doctrines spread proclaiming that government debt is a free lunch, never needing to be repaid. MMT preached that “there is always slack” in the US economy, so one never need worry about stimulus causing inflation. Borrow or print a few trillion dollars of money, they said, and don’t worry about paying it back.

Well, in 2021 we did exactly what this consensus asked. And we got inflation. That is an important lesson. There was genuine uncertainty about what would happen, in the 2010s, if a massive fiscal-monetary stimulus were attempted. Now we know. “Demand” bashed in to the brick wall of supply, and surprisingly soon. If you want more economic growth now, there is no alternative but incentives and microeconomic efficiency; growth. If you want to borrow and do not wish to cause inflation, you must have a plan for paying it back. Economics is back to normal. Washington has not woken up to this slap-in-the-face lesson, perhaps because it interrupts such pleasant dreams. It seems like Tokyo is more awake.

(Due to Substack length limitations, this post continues in Part 3.)

I draw here on The Fiscal Theory of the Price Level, “Expectations and the Neutrality of Interest Rates,” “Fiscal Narratives for US inflation,” and “Fiscal Histories,” all on my website.

I don’t believe this lesson is true, that a govt needs a plan to repay the borrowed money to avoid inflation.

The lesson is that, with low amounts of borrowing in a market economy, the govt can get a 2%? 1%? O.5%? (Of annual GDP) Free lunch. Not an “all you can eat, for all” , but some significant amount. The Trump amount was the maximum, the Dem Biden amount was too much.

Japan’s never ending debt growth has been at or below Max Free Lunch deficit, for 30 years (less than forever).