Inflation and relative prices

My last post emphasized the conceptual difference between inflation and relative prices. When you go to Japan, there are two more zeros on every price. That’s the price level, the nominal anchor. That difference has nothing to do with relative demand for sushi vs. hamburgers, productivity, or anything but the nominal anchor. The core economic idea of inflation is that common component in all prices and wages.

However, along the way, there is lots of relative price variation, and relative price variation can have a big “temporary” effect on inflation. Temporary in quotes because it can be big and last for years.

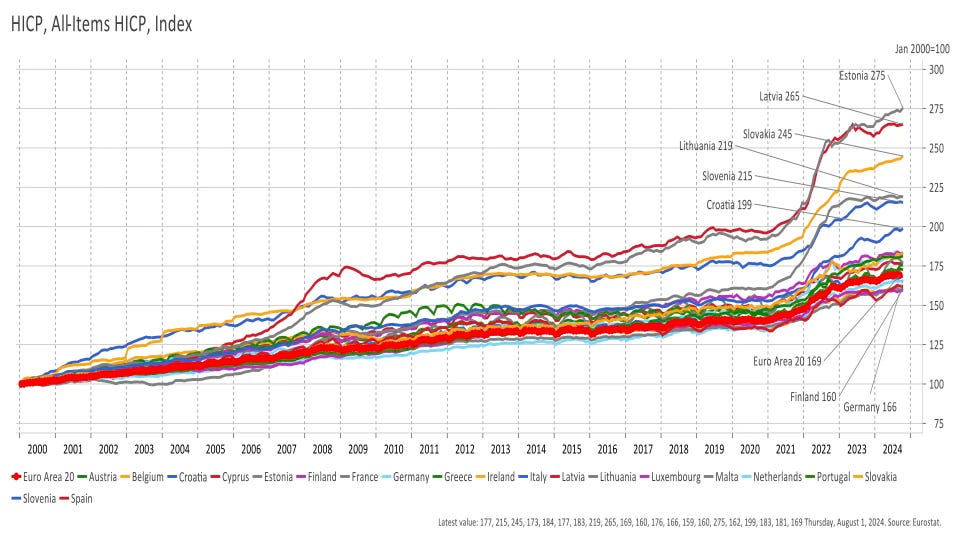

To make the point, here is inflation in all the euro area countries. (Source, the ECB’s remarkably dysfunctional inflation dashboard.) By the economic definition of inflation, the value of money, inflation is the same in all these countries. They share a common currency, and the value of that currency is what it is. They have the same monetary policy, and the same fiscal backing of that currency. Individual fiscal policies don’t matter to inflation meaning the underlying value of the currency. Every difference in price of the same good across euro area countries is a relative price difference.

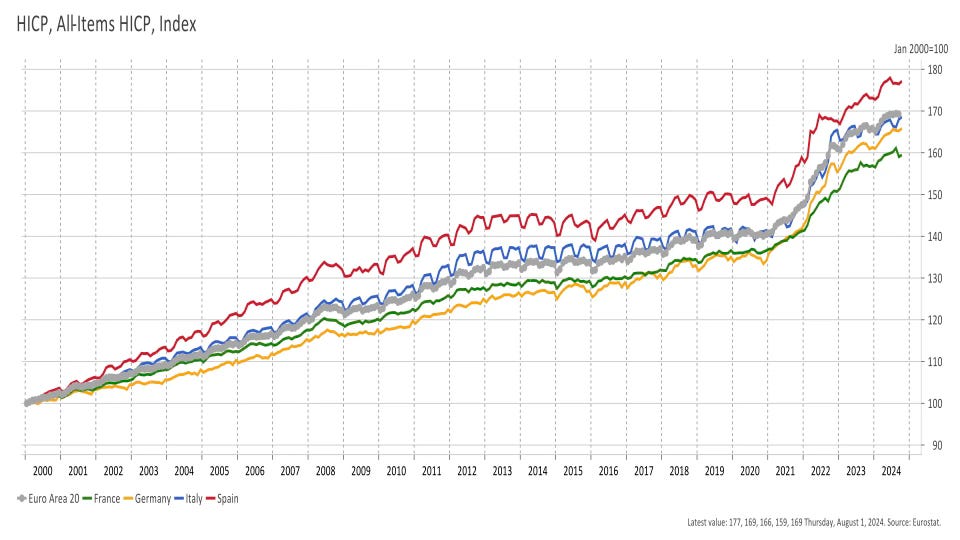

But, as you can see, those relative price differences are pretty big! They are of course especially big in the small countries, and less so in the big countries:

Italy vs. Spain can never diverge as far as the US and Japan diverge. But they can diverge a few percentage points.

Supply shocks, relative demand shocks, tariffs, sales taxes, productivity, etc. can influence measured inflation for quite a while, even though they are relative price shocks.

(I wanted to make a plot of the price levels in the euro area, to show they diverge but trend together, but I gave up on the ECB’s data website. I encourage someone else to make the plot and I’ll link to it.)

Update: I went out to dinner, and Juhana Hukkinen at the Bank of Finland kindly plotted the price levels in the euro area and sent them to me.

From 2000 (normalizing the price levels to be the same in 2000):

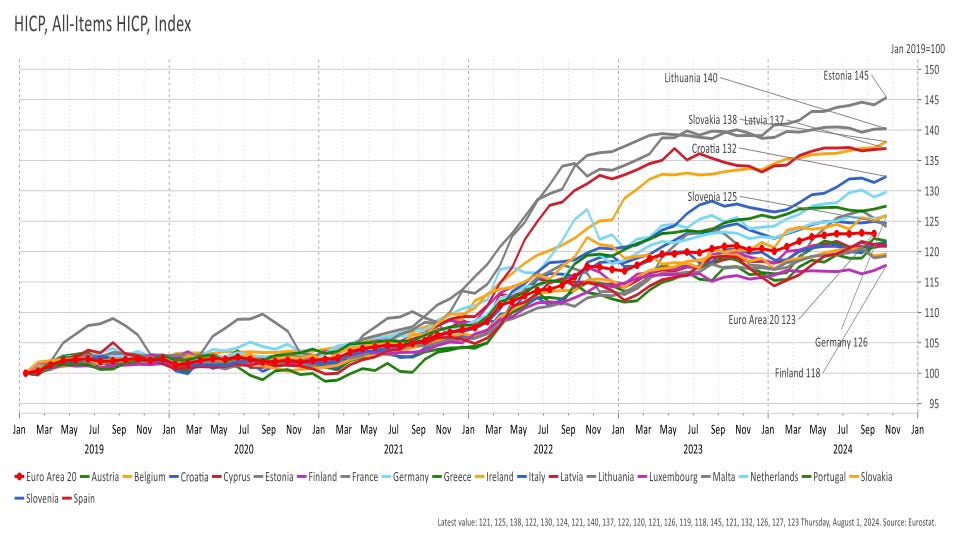

From 2019:

Across the larger group of countries, the price level in new small countries like Lithuania, Estonia, Croatia, Slovenia drifts away from those in the other EU countries. The inflation shocks lead to permanent price level differences.

Looking among larger EU countries, from 2000

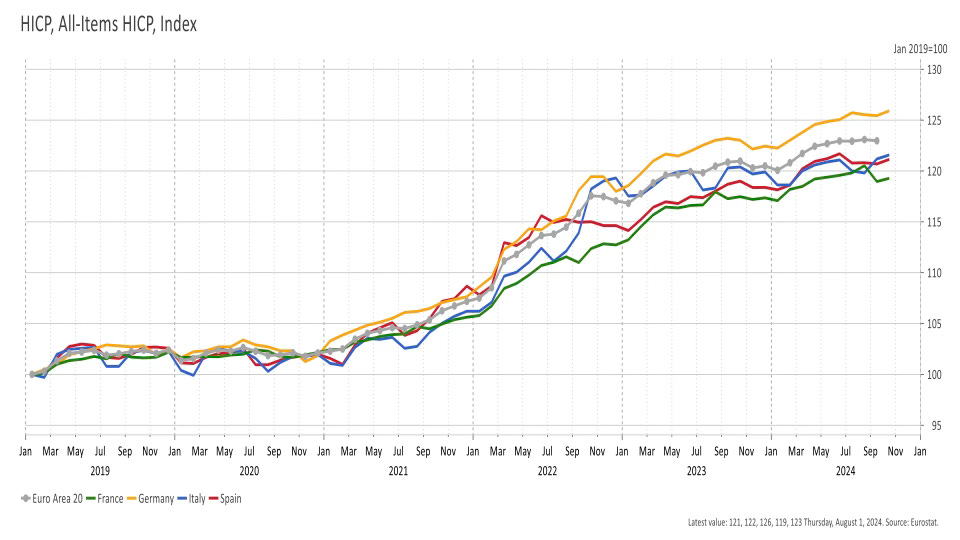

and from 2019,

Price levels in the core countries France Germany Italy and Spain are much closer to each other. However, the same pattern shows up: price levels drift apart over time.

This is profoundly disconcerting. I expected that price levels would be cointegrated, and converge in the long run. It might take a while, but they should converge eventually.

This is the same issues as “purchasing power parity” in international economics. The dollar and yen start worth the same amount, and a hamburger costs 50 cents here and half a yen there. After decades of inflation, the dollar is worth 100 yen and a hamburger that costs $5.00 in the US costs 500 yen. The real exchange rate should revert.

With the same currency in the euro, we are seeing real exchange rates across the euro area. They seem to drift apart.

I presume this pattern comes down to “nontradeables,” things like the price of housing and services like haircuts. As the new countries grew much faster than the rest of Europe, prices of nontradeables rose. Prices may in fact be converging. Price indices start at 100, but relative prices were not all the same in 2000. Haircuts in Lithuania used to be cheap, but as wages rose haircuts got more expensive, and stayed that way. Similarly, Germany rising relative to Italy may reflect somewhat less slow growth in Germany than Italy.

This pattern may also reflect some quirk of how price indices are constructed. They are designed to measure inflation rates over relatively short time intervals. Experts, feel free to write.

Next, prices across states in the US. My sense it that there are large movements in relative prices here too, though we use a common currency. Driving from Texas to California almost feels like traveling to Japan when you look at the prices.

The distinction you have made in your last posts between the difference between movements in relative prices and prices in general is crucial for a proper understanding of inflationary factors and forces.

You also list a variety of reasons behind changes in relative prices often confused for general inflationary price changes.

But it is worth pointing out there is a connection between monetary changes that end up influencing prices in general and relative prices. This factor has been emphasized since Richard Cantillon and David Hume in the 1700s, John E. Cairnes in the 1800s, and “Austrian” economists like Ludwig von Mises and F.A. Hayek in the 1900s.

All changes in the supply of money are injected into (or withdrawn out of) the market somewhere and proceeds to pass from hand to hand as changes in the demands for various goods in some temporal sequence. The structure of relative prices and wages, profit opportunities and resource uses (labor, capital), are effected for as long as the monetary changes continue and have no fully and finally had there impact throughout the economy.

Thus, changes in prices in general (price inflation or price deflation) are never completely separable from relative price changes due to the inherent “non-neutrality” of money and monetary changes.

OT but begging for a reply.

Yes, Bank Indonesia (BI) has been buying government bonds as part of its debt monetization program:

2021: BI bought about 215 trillion rupiah of government bonds

2022: BI bought 224 trillion rupiah of government bonds

2024: BI became the largest holder of Indonesia's sovereign debt, with 23% of the total rupiah bonds

BI's ownership of government bonds allows it to:

Stabilize bond yields to prevent outflows during market volatility

Curb volatility during an unfavorable global market environment."

---30---

Indonesia now has below-target inflation, sub 2%.

Of course, Japan did the same thing forever.

Is this the solution to the US debt bill?

We can rest assured Congress and Trump are not going to balance the budget.

Yet central banks that build balance sheetห do not result in inflation. But they do remove debt from taxpayer shoulders.