Balancing the Budget, P.J. O'Rourke

It’s so hard, everyone says. No it isn’t.

Recently I found out that P.J. O’Rourke’s masterpiece of political philosophy, Parliament of Whores, is online, for free. In your archives of classics, this book should go alongside Plato, Macchiavelli, Hume, and the Federalist Papers. (And George Will’s Conservative Sensibility.) People only don’t take it seriously because it is so hilarious.

One day, P.J. decided to see if he could balance the budget. Start on p. 99. (I won’t indent. All the rest if from P.J.)

****

The good news is I balanced the budget. It took me all morning but I did it. You’re probably wondering how a middle-aged amateur—who is under the impression that double-entry bookkeeping is what you do when you have to explain that you spent the taxpayer’s money on obscene performance art and who can’t count three without removing a mitten—did this. It helps that I am not up for reelection to the position of being me. I also tried to avoid looking for ridiculous examples of government waste. This is the first mistake made by most budget critics. They page through the minutiae in the “Notes and Appendices to the U.S. Budget,” sifting the “Detailed Budget Estimates by Agency” section until they come up with something like the Department of the Interior’s Helium Fund. Which really exists:

The Helium Act Amendments of 1960, Public Law 86-777 (50 U.S.C. 167), authorized activities necessary to provide sufficient helium to meet the current and foreseeable future needs of essential government activities.

Then the budget critics grow very indignant or start making dull, budget-critic-type helium jokes. The Helium Fund is amazingly stupid, even by government standards, but it only costs around $19 million—.0015 percent of 1991 federal spending. This chapter would be as large as the budget itself if I tried to balance that budget by eliminating Helium Funds. And, if you think about it, running a Helium Fund is just the kind of thing our politicians should bedoing. It’s much less expensive and harmful to the nation than most of what they do, plus, with any luck, they’ll float away.

The other secret to balancing the budget is to remember that all tax revenue is the result of holding a gun to somebody’s head. Not paying taxes is against the law. If you don’t pay your taxes, you’ll be fined. If you don’t pay the fine, you’ll be jailed. If you try to escape from jail, you’ll be shot. Thus, I—in my role as citizen and voter—am going to shoot you—in your role as taxpayer and ripe suck—if you don’t pay your share of the national tab. Therefore, every time the government spends money on anything, you have to ask yourself, “Would I kill my kindly, gray-haired mother for this?” In the case of defense spending, the argument is simple: “Come on, Ma, everybody’s in this together. If those Canadian hordes come down over the border, we’ll all be dead meat. Pony up.” In the case of helping cripples, orphans and blind people, the argument is almost as persuasive: “Mother, I know you don’t know these people from Adam, but we’ve got five thousand years of Judeo-Christian-Muslim-Buddhist-Hindu-Confucian-animist-jungle-God morality going here. Fork over the dough.” But day care doesn’t fly: “You’re paying for the next-door neighbor’s baby-sitter, or it’s curtains for you, Mom.”

Armed with these tools of logic and ethics, I went to work. I took the original 1991 Bush budget because, as I mentioned, it was the only budget available in detailed form and, also, because—for all the budget-crisis noise—the Bush budget was not very different from the final budget approved by Congress. I turned to the “Federal Programs by Function” section, being careful to work in the “outlays” column, which shows what we really spend, rather than the “budget authority” column, which shows what we say we’re spending. I ignored all appropriations of less than half a billion dollars—even NEA grants—as chump change. And I used the “unified budget” figures to avoid most off-budget spending dodges.

Then I cut all international security assistance (it hasn’t generated any international security that I’ve noticed), all foreign information and exchange activities (if foreigners want information, they can subscribe to Time) and all international-development and international financial program funds (let them spend their own money for a change). In fact, I cut the entire international affairs “budget function,” as they call it, except for food aid, refugee assistance and conduct of foreign affairs (because the State Department gives us a way to ship Ivy League nitwits overseas). Total savings: $13.6 billion.

In the interest of the free-market ideology, for which America is a symbol worldwide, I cut the whole energy budget (leaving only the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, because it upsets tree huggers). Total savings: $2.7 billion. In the natural resources and environment budget function I cut all spending for water resources (if they want water out West, they can go to the supermarket and get little bottles of it the way the rest of us do) and recreational resources (people who can afford Winnebagos can afford national park entrance fees). Total savings: $6.1 billion.

I cut all farm income stablization: $12.7 billion. And I made the Postal Service pay for itself or sell out to Federal Express: $2.1 billion. I dumped savings-and-loan bailout costs (which are seriously underestimated in the Bush budget, by the way) back on the savings-and-loan industry, where they belong, and cleaned out the rest of the government’s involvement in mortgage credit and deposit insurance: $13 billion. And I ditched other advancement of commerce (if it advances commerce so much, why isn’t it paying for itself?): $2.1 billion.

I got rid of all transportation spending. Let ‘em walk: $29.8 billion.

You may have noticed how well community and regional development has worked. Examine Detroit or downtown Newark. This is also the part of the budget where the government recently found $500,000 to restore Lawrence Welk’s birthplace and make Strasburg, North Dakota, a tourist attraction. I eighty-sixed all of this except for disaster relief: $6.6 billion.

Per-pupil spending on public school education has increased by an inflation-adjusted 150 percent since 1970, while reading, science and math scores have continued to fall. The hell with the little bastards: $21.7 billion.

Training and employment is properly the concern of trainees and employers: $5.7 billion. Insurance companies should gladly pay for consumer and occupational health and safety: $1.5 billion.

If I outlaw rent control and discriminatory zoning and give landlord the right to evict criminals and deadbeats, I should be able to cut housing assistance in half: $8.8 billion.

And I just lowered food prices by eliminating farm subsidies, so I can also cut food and nutrition assistance by 50 percent: $11.7 billion.

If unemployment insurance is really insurance, it ought to at least break even: $18.6 billion.

So-called other income security, except what goes to refugees or the handicapped, probably does not meet the gun-to-mom’s-head test: $19.9 billion.

And federal litigative and judicial activities should turn a profit in these days of white-collar crime and RICO seizures: $4.3 billion.

That’s $180.9 billion cut from the budget already, and I haven’t even touched defense or the larger entitlement programs. Next let me “means test”—that is throw the rich people out of—Social Security, federal and railroad employee pensions, Medicare and veterans’ benefits. The government figures it loses $19.8 billion per year by making only half of Social Security benefits liable to income tax. That $19.8 billion is 8.25 percent of Social Security spending. I’ll take that 8.25 percent plus another 8.25 percent from well-off geezers, and I’ll bounce the richest 3.5 percent of the old farts from the system entirely. Thus, I can cut Social Security—and analogous programs—by 20 percent, for a savings of $71.9 billion.

National defense is tough. I like having lots of guns and bombs. Besides, you can always turn an aircraft carrier into a community center (plenty of space for basketball courts), but just try throwing a rehabilitated drug addict at a battalion of Iraqi tanks. Nonetheless, something has to go. I had friends at Kent State, so screw the National Guard: $8.4 billion. And I cut air force missile procurement by half since, for the moment, we don’t have anyone to point those missiles at: $3.6 billion. I also cut military research and development by 25 percent and sent the weapons wonks back to playing Dungeons & Dragons on college computer systems: $9.2 billion. Military construction can stop (if they need money for paint or something, they can sell a few bases to the idiots at the savings-and-loan bailout’s Resolution Trust Corporation, who’ll buy anything): $5.5 billion. And I turned the Corps of Engineers over to private enterprise. Just let the Mississippi wash the Midwest away if people won’t pay their flood-control bills: $3.3 billion. This gives me $30 billion in military cuts.11

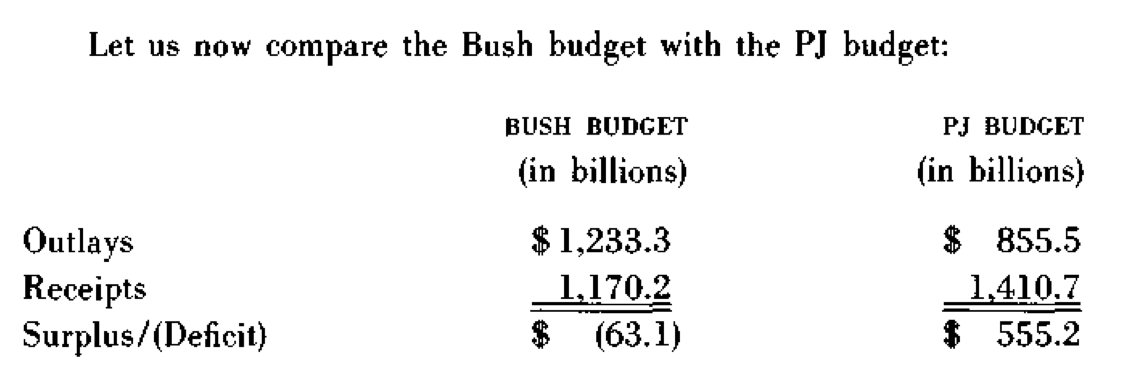

Add it all together, and I’ve cut $282.8 billion, leaving a federal budget of $950.5 billion, to which I apply O’Rourke’s Circumcision Precept: You can take 10 percent off the top of anything. This gives me another $95 billion in cuts for a grand total of $337.8 billion in budget liposuction.

Now for revenues. I’m a real Republican (unlike some current presidents of the United States I could name), so I won’t raise taxes; but since I’m temporarily in charge of the federal budget, I don’t mind squeezing the bejabbers out of the people who pay them. There’s an appendix to the federal budget called “Tax Expenditures.” These are revenues that the government loses because of things you can deduct when you figure your income taxes. It takes fourteen pages just to list them all. Tax expenditures used to be called loopholes when they were mostly for rich people. And some tax expenditures still mainly benefit the rich: Keogh plans and deductions for mutual-fund-management expenses, for instance. These cost the government $2.1 billion. But most TEs are middle-class subsidies of one kind or another. The revenue lost to home-mortgage-interest deductions alone is $46.6 billion. Taxes not paid on employer-provided pension-plan contributions, insurance premiums and health benefits equal $89.8 billion. Deductions of state and local taxes cost another $34.3 billion. Combine these with untaxed interest on life-insurance savings, home-sale capital-gains exemptions, tax deferrals on savings-bond interest, employee stock plans, IRA contributions, child- and dependent-care expense deductions and earned income credit, and the middle-class take from tax expenditures is $209.9 billion.

Various businesses get another $6.9 billion in egregious tax expenditures—oil- and mineral-depletion allowances, indulgent accounting rules for corporations with branches overseas, special treatment for credit unions and timber companies and tax credits for investing in Puerto Rico andGuam. And tax-free state and municipal bonds cost the federal government $21.6 billion. All told, at least $240.5 billion worth of tax expenditures should be just plain taxes.

Not only is the PJ budget balanced, but every taxpayer will get a $5,000 rebate check from the government this year, and next year there will be a 39-percent cut in all personal and corporate income tax rates. This ought to set the economic Waring blender on puree and make up for whatever minor inconveniences I’ve caused with lowered government spending and elimination of tax deductions. Was that so hard?

My budget cuts are (what fun) ham-fisted. But smarter, fairer people who know what they’re talking about could cut this much and more. Why don’t they? They don’t because they don’t quite have to yet. Despite the alleged panic over the budget of ‘91, the deficit and the national debt aren’t big enough to wreck America. In the 1980s the annual budget deficit averaged 4.1 percent of the gross national product. This isn’t so bad compared with the average deficit of 22.8 percent of GNP during World War II. And our total national debt now stands at 56 percent of the gross national product, not much worse than the 53 percent of GNP national debt we had at the end of the Great Depression. The problem is we aren’t in a world war or a great depression (although both those options are being explored). In a relatively peaceful, relatively prosperous era, there’s no excuse for these budget trends. There’s also no likelihood that they’ll change. The problem isn’t a Congress that won’t cut spending or a president who won’t raise taxes. The problem is an American public with a bottomless sense of entitlement to federal money.

If just two of our federal programs—Social Security and Medicare—continue to expand at their present rate, they will cost the nation $1.4 trillion in 2010, more than the whole current budget. Maybe our future economy will survive this expense. But is it wise in any case to put the awesome power of such spending in the hands of our silly government? This is not a matter of being conservative or liberal. Do you want Teddy Kennedy or Newt Gingrich to run your life? Yet everybody is asking for a federally mandated comprehensive national-health-care program.

Selfishness consumes our body politic. The eighteenth-century Scottish historian Alexander Tytler said:

A democracy cannot exist as a permanent form of government. It can only exist until a majority of voters discover that they can vote themselves largess out of the public treasury.

Our modern federal government is spending $4,900 a year on every person in America. The average American household of 2.64 people receives almost $13,000 worth of federal benefits, services and protection per annum. These people would have to have a family income of $53,700 to pay as much in taxes as they get in goodies. Only 18.5 percent of the population has that kind of money. And only 4.8 percent of the population—12,228,000 people—file income tax returns showing more than $50,000 in adjusted gross income. Ninety-five percent of Americans are on the mooch.

***

Of course, this is a bit out of date. But not as much as you think, if you just multiply all the numbers by about 5. I would prioritize different things. I’m more attuned to fixing disastrous incentives, especially health care. The habit of doling out money to states and NGOs was not quite as prevalent back then. But it does make clear that balancing the federal budget is an easy economic question. And it’s a lot of fun. The rest of the book is even better.

The end of the book expands on this insight. Ruminating on the town meeting of Blatherboro New Hampshire, supposedly the archetype of democracy, trying to ban a golf course:

***

The whole idea of our government is this: If enough people get together and act in concert, they can take something and not pay for it. And here, in small-town New Hampshire, in this veritable world’s capital of probity, we were about to commit just such a theft. If we could collect sufficient votes in favor of special town meetings about sewers, we could make a golf course and condominium complex disappear for free. We were going to use our suffrage to steal a fellow citizen’s property rights. We weren’t even going to take the manly risk of holding him up at gunpoint.

Not that there’s anything wrong with our limiting growth. If we Blatherboro residents don’t want a golf course and condominium complex, we can go buy that land and not build them. Of course, to buy the land, we’d have to borrow money from the bank, and to pay the bank loan, we’d have to do something profitable with the land, something like . . . build a golf course and condominium complex. Well, at least that would be constructive.

We would be adding something—if only golf—to the sum of civilization’s accomplishments. Better to build a golf course right through the middle of Redwood National Park and condominiums on top of the Lincoln Memorial than to sit in council gorging on the liberties of others, gobbling their material substance, eating freedom.

What we were trying to do with our legislation in the Blatherboro Town Meeting was wanton, cheap and greedy—a sluttish thing. This should come as no surprise. Authority has always attracted the lowest elements in the human race. All through history mankind has been bullied by scum. Those who lord it over their fellows and toss commands in every direction and would boss the grass in the meadow about which way to bend in the wind are the most depraved kind of prostitutes. They will submit to any indignity, perform any vile act, do anything to achieve power. The worst off-sloughings of the planet are the ingredients of sovereignty. Every government is a parliament of whores.

The trouble is, in a democracy the whores are us.

****

This paragraph was written before the commencement of Operation Desert Storm. Therefore, all these military spending cuts should be restored. Then let’s hold the Saudi Arabians, Kuwaitis and whatever Iraqis remain alive at gunpoint and make them pay the costs.

John, I think you cut this off shortly before my favorite line in the book, which is when PJ describes the typical experience of attending a New England town meeting as like "being a cell in a plant." An all-timer that has stuck with me ever since I first read the book 20+ years ago.

The three others that I have always remembered are "you can take 10% off the top of anything," the gun-to-the-head method of analyzing spending, and PJ's admonition that it's impossible to "observe Congress on a typical day" because on a "typical day" Congress isn't actually in session. Great, classic stuff.

Also - I think you are right that many of these ideas are taken less seriously than they should be because PJ is so funny. RIP!

P. J. O'Rourke was an amazing satirist. He was able to create humor and education at the same time. I think P. J. would have owned twitter/X without even trying.