Trump's monetary policy desires aren't crazy

This is a WSJ OpEd that I will publish in full in 30 days. Follow the link if you’re a subscriber now.

I see three broad desires: Interest rates should be lower, in part to lower interest costs on the debt. The Federal Reserve should be less independent, subject to more “democratic accountability.” And “exorbitant privilege” or “reserve currency status”—that the world wants to hold our money and buy our debt, sending us goods in return—damages the U.S.

Interest rates

Lower interest rates leads quickly to “that will cause inflation.” (And, in monetary policy circles, “you idiot.”) But to be honest we really don’t know if, how much, or how soon.

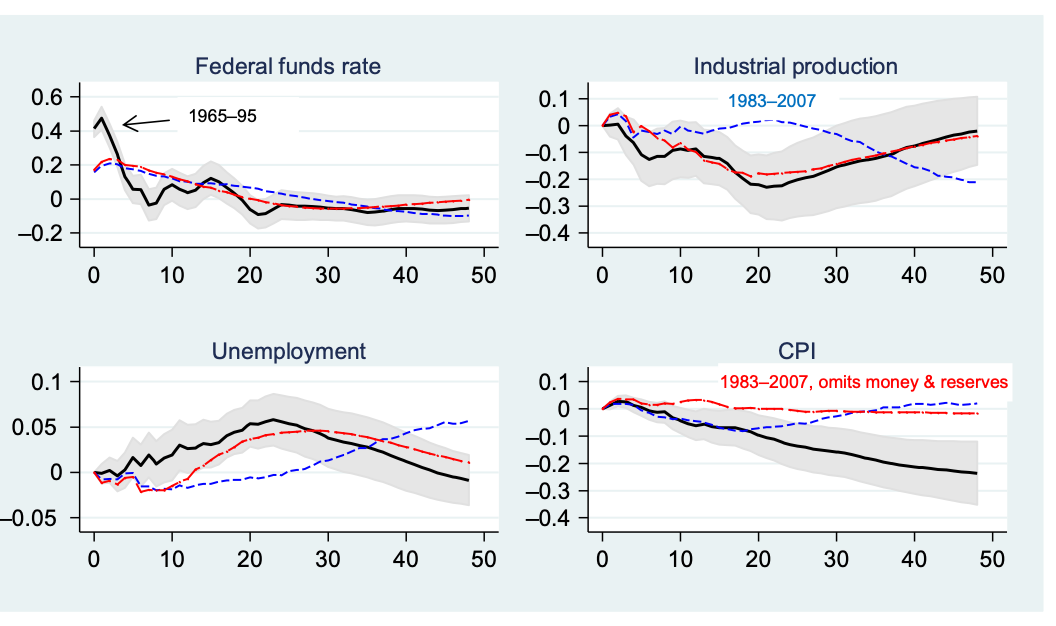

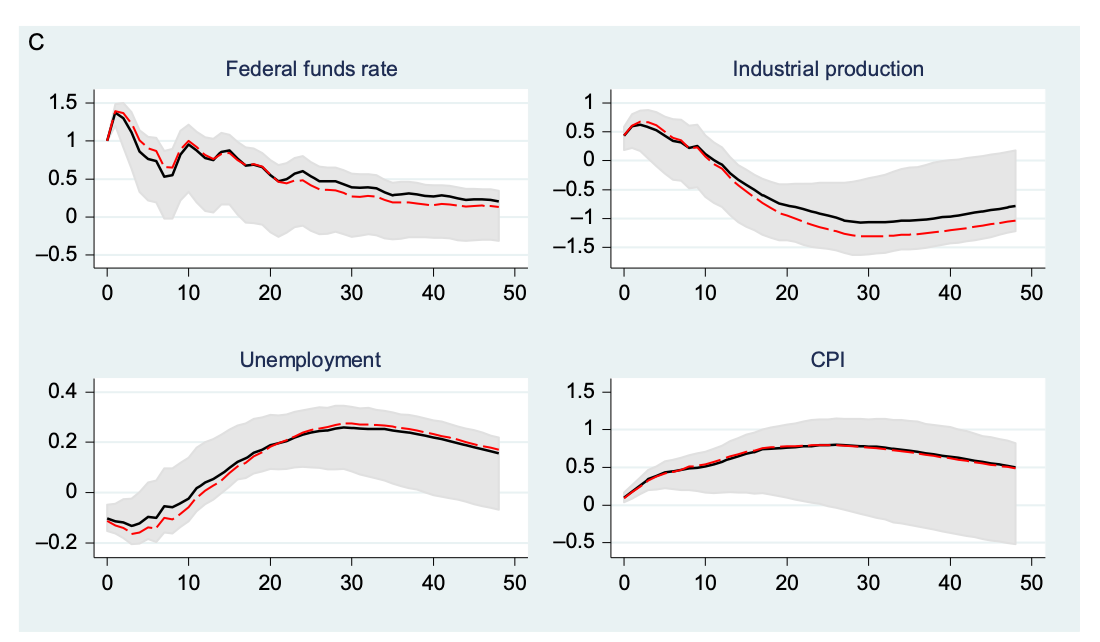

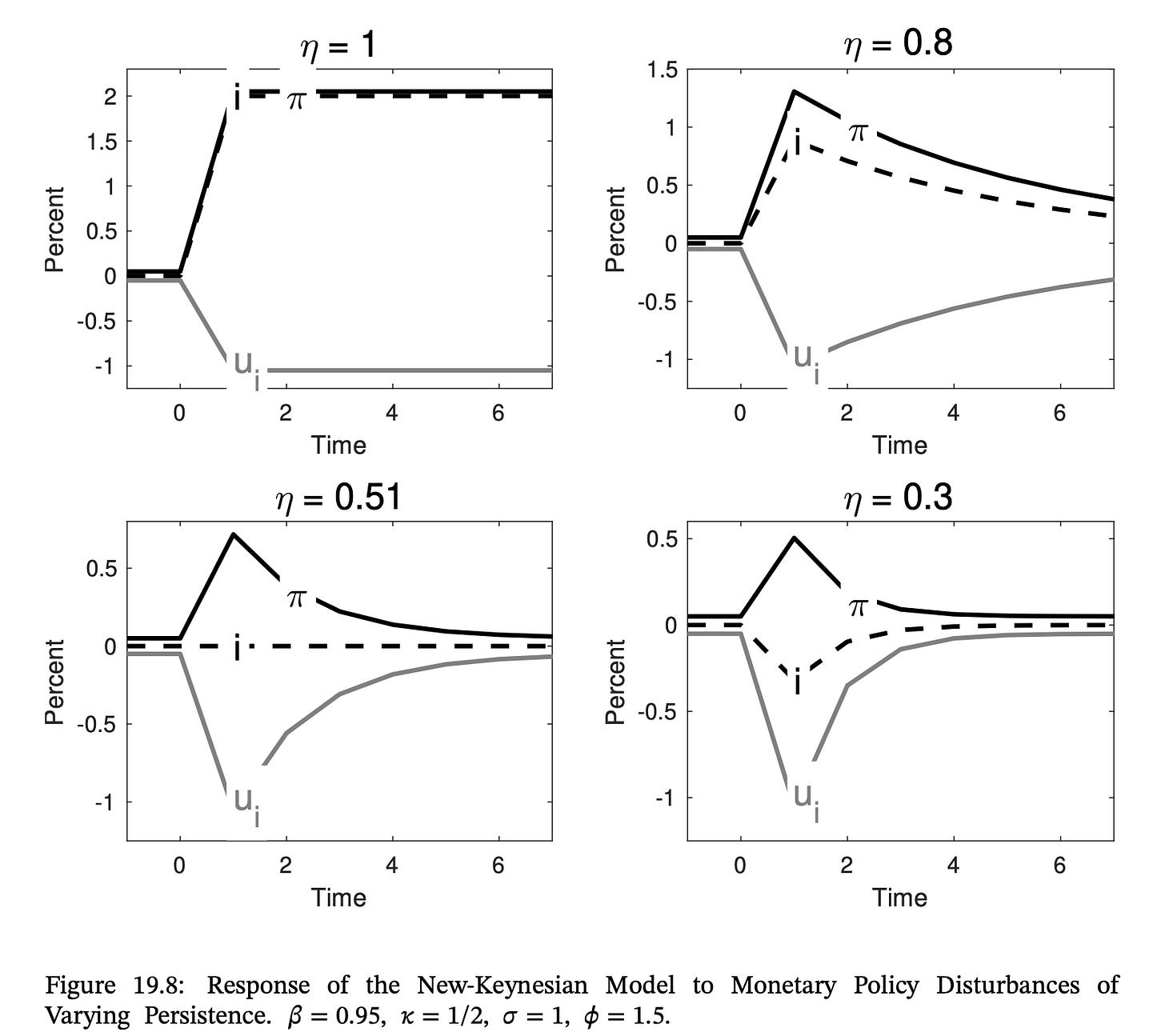

Here’s some standard empirical estimates from Valerie Ramey’s splendid review. Each of these plots the reaction of the level of the CPI (not the growth rate) to the indicated federal funds shock.

The price level goes nowhere for a year, and then maybe gently drifts down, or maybe not in the last picture. This is hardly the pearl-clutching inflation will be here in a few months that you might infer. The real economy reacts more quickly and reliably.

Moreover, all this empirical work only measures the response to the temporary interest rate decline plotted in the top left, and none of them ask whether fiscal policy changed at the same time. They don’t measure a permanent rise or decline separate from any fiscal policy change.

Well, as we say at the University of Chicago, so much for the real world, but how does it work in theory?

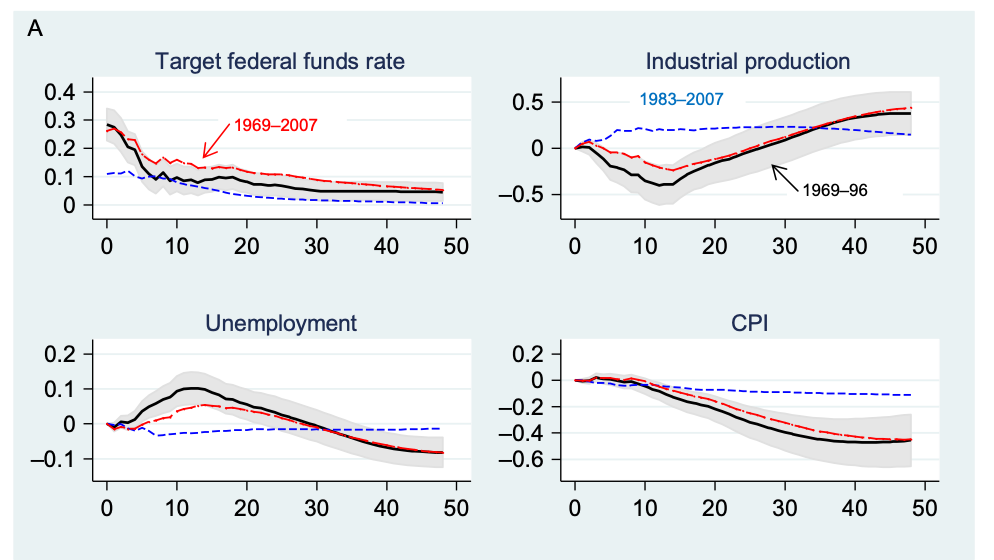

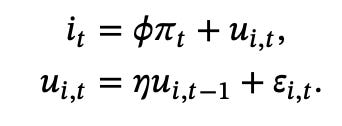

Mainstream, or “new Keynesian,” economic theory predicts that a permanently lower interest rate will eventually lower inflation, other things (especially fiscal policy) held constant, even though inflation may temporarily rise. This is an unsettling implication that the theory’s largely center-left practitioners have trouble applying to reality, but there it is. Sure, maybe decades of consensus theory is all wrong. Economists have pursued wrong theories before. But if it’s in the equations of your own models, the proposition at least bears consideration.

This is probably the paragraph that will cause the most trouble. The WSJ editors couldn’t believe it. But it’s true. Here is a graph from Fiscal Theory of the Price Level:

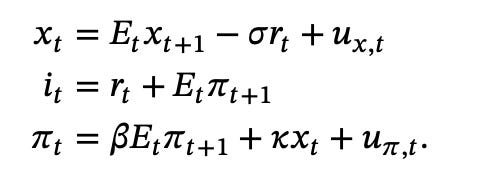

The model is the simple textbook new Keynesian model, with no FTPL funny business,

Start in the bottom right. This is the standard result: Transitory lowering of interest rates raises inflation.

But what if the shock is more permanent? The top left panel gives the ultimate case: a permanent rise in the interest rate leads to an immediate and permanent rise in inflation! And, contrariwise, a permanent decline in the interest rate leads to a permanent decline in inflation.

The top right shows a persistent but not permanent interest rate movement, which still pushes inflation in the same direction. The lower left panel shows how a shock with just the right persistence can implement an open mouth operation: inflation changes with no movement of interest rates at all. I left this out of the Op-Ed as nobody in the real world would believe that current models permit such a thing, but they do. The new-Keynesian model is about equilibrium selection, not about interest rates. But I digress.

There is an inexorable logic to the proposition. The economy is surely neutral: higher interest rates go with higher, not lower, inflation in the long run. 100% inflation has to go with 110% interest rates. If the economy is also stable, then raising interest rates must eventually raise inflation, and lowering interest rates must eventually lower inflation. Now, it could go the other way in the short run, as it does not in this textbook model. I’ve been working hard to produce models that do that. But that lower rates lower inflation in the long run is hard to avoid, as you need to abandon neutrality or stability to get it.

How could higher nominal interest rates raise inflation? Well, let’s just put words in to the equations of the model. If the Fed raises the nominal interest rate and inflation does not change, the real interest rate has risen. That induces people to save more and consume less today, and then to consume more with the greater returns to that saving next year. Doing so puts downward pressure on today’s price level, and upward pressure on next year’s price level. Expected inflation — the rise in prices from now to next year — rises. It’s the contrary intuition that’s hard, because it requires people to be dumb about their expectations. In fact that higher interest rates should raise inflation is as natural as higher money growth should raise inflation. It’s just too many years of static ISLM repetition that get one thinking otherwise.

You might say that all this new-Keynesian stuff is nonsense, and all of macro took a wrong turn in 1972, the year Lucas published his “expectations and the neutrality of money,” and he, Sargent, Sims, Prescott, Hansen, Phelps, etc. set off to destroy ISLM and pick up Nobel prizes for doing so. That’s the view of Alan Blinder, who basically wrote a whole book saying so, Paul Krugman says so, and it’s not an uncommon view. Well, I think Keynesian economics went down a 40 year wrong track, so it’s certainly possible new-Keynesian economics also did so.

But I’m not here to argue what’s right, just what is acceptable for discussion in polite company. Given that this is the utterly textbook model (See Woodford or Galì), that has completely dominated academic publication since about 1990, surely we—and especially authors and users of those models— should not be out making fun of Trump for not knowing economic basics. Just what is the effect of persistently lower interest rates is a really interesting and open topic worthy of civilized debate.

The historical record is also mixed. That inflation went nowhere over a decade of near-zero interest rates, and three decades in Japan, seems to confirm this theoretical view that inflation is stable with a fixed interest rate—and that inflation will eventually follow higher or lower interest rates. Yes, low interest rates that financed large deficits contributed to inflation in many countries. But if a government doesn’t expand fiscal policy, the record is less clear. Yes, low interest rates in response to “supply” shocks, such as in the 1970s and 2020s, coincided with inflation. But the exact effect of low rates, and of other fiscal and nonfiscal responses, is also murky.

“What about Turkey?” I hear you ask immediately. (There is a chapter in FTLP on that.) The proposition only holds for coordinated monetary and fiscal policy. Lower interest rates used as financial repression to finance out of control spending surely do cause inflation, in the model as in real life. Lower interest rates alone, with a government that does not ramp up spending, is another question. Eduardo Loyo showed that when Brazil raised interest rates without changing fiscal policy, inflation went up as interest costs on the debt mounted. If that’s right, so is the opposite sign. Milton Friedman (1968) cited post WWII interest rate pegs that blew up into high inflation. But those too had huge budget deficits, and the low interest rates were attempts at financial repression to finance those fiscal policies. And they were part of attack-prone fixed exchange rates and a gold standard. The 1980s were joint fiscal, monetary and microeconomic reform, not just high interest rates. And so on. The evidence is not so clear.

We economists don’t know with certainty just if, how, under what circumstances or how quickly low interest rates lead to inflation. I believe they do, despite the equations of my models, but that’s far from science.

I emphasize, the whole question is low interest rates without additional fiscal deficits. The Trump economic team is flirting with inflation. But the danger is unreformed deficits, which mean the next crisis could cause more inflation than the last one. That’s not monetary policy. I think their strategy is to hold down interest costs on the debt for a few years, and then supercharged economic growth coming from their tariff policies (unlikely) or AI (maybe) will solve the fiscal problem. Good luck.

(I wrote “believe,” the journal changed it to “suspect,” and I’m trying to get it changed back.)

Independence

The Fed has vastly expanded, going in to fiscal policy, political waters, and telling banks what to do. It has a few huge failures on its hands, including the financial crisis, 10% inflation, and the SVB collapse which though small shows just how hopeless the Fed’s asset risk regulation is. The Fed bails out and adds “tools” over and over to meet each perceived crisis, but just pats itself on the back with its expanded power and never stops to think, how can we keep from having to do this over and over again.

It is not unreasonable to ask about reform. And given a desire to reform, the choice is to keep the expanded toolkit and bring it under more politically accountable hands, or to reduce the scale of the Fed via more stringent mandates and accountability. I prefer the latter, though it puts a lot of faith in Congress’ ability to craft structural reforms.

But it’s not a stupid discussion to have. I will be at a Peterson Institute Conference on central bank independence October 31 that will explore the issues.

Trade and privilege

I recently found The Cross of Gold by Davis Kedrosky and Nuno Palma. Portugal found gold in Brazil. Gold was Europe’s money. Portugal used this money to buy goods, not to invest. When it ran out, Portugal was poor. Printing money and debt to finance trade deficits that go in to consumption isn’t always a good thing in the end. I think both the decision not to invest and the poor investment opportunities is the central problem.

Thus tariffs, capital controls, securities taxes and industrial policy will all make matters worse. Get out of the way instead.

But there is an issue, to be discussed, about just why we use the worlds’s bounty to consume.

Bottom line

My fellow macroeconomists, mostly Trump-hating Democrats or Never-Trump Republicans, are mostly treating this monetary policy news as if it is completely delusional. Unlike the economic effects of tariffs, though, that’s not really honest. We would do better to have a respectful debate.

(I do not discuss here his efforts to fire Lisa Cook and get Jay Powell to resign. And please, just because I’m willing to listen to three Trump propositions does not imply an endorsement of everything he does. “What about when Trump did x?” is not a logical reply. Let’s stick to the point and what I actually say.)

Friends, in this essay you read an honest, intelligent, informed professional economist who has no bone to pick. Is it not refreshing and inspiring? I am but the first adjective, but I agree completely with professor Cochrane's assessment of the 40-year blind alley.

That's going to stir the pot. It's good to find out what's in the pot, particulary since we have been eating this stuff for a long time. I thought it was beef bourguignon, Prof. Cochrane says it is roadkill. Let's find out. Time for the science of economics to confront the rebutable presumption.