Tax talk

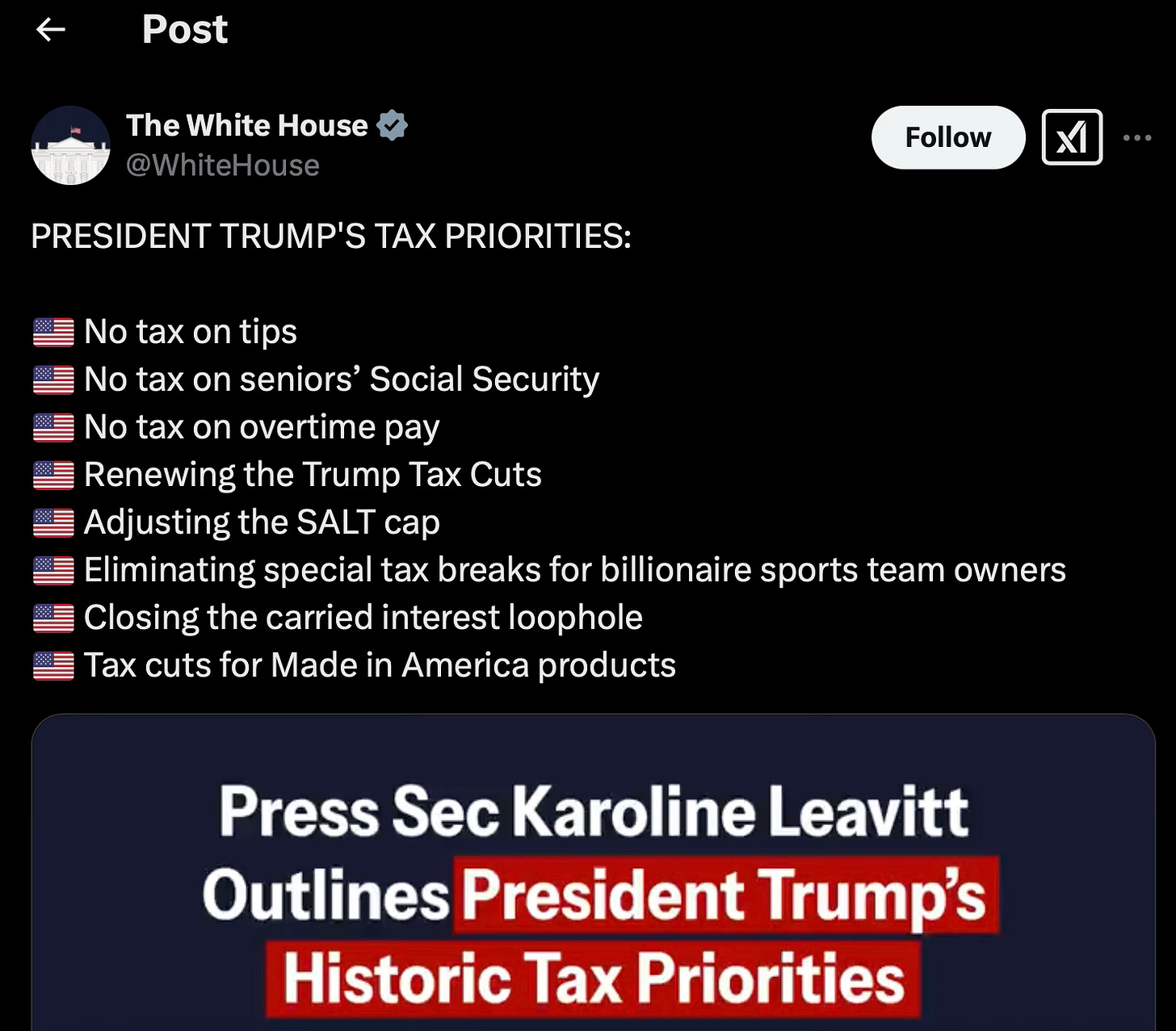

Last week the administration announced President Trump’s tax proposals:

My first impressions follow. (NB I have not looked deeper than this source. )

I view my job as offering some sensible analysis between the predictable Trump derangement disaster mongering, and the equally predictable unqualified cheering. And my job is to emphasize incentives. The economists’ mantra is “cut tax rates” not “cut taxes.”

This isn’t the tax reform you’re looking for

So don’t complain. At some point the US needs a deep tax and spending reform, to raise revenue while broadening the base, improving incentives for economic growth, and solving the long term budget problem. This isn’t it. This isn’t supposed to be it. The President made campaign promises on taxes. Appropriately for the first month in office, these proposals fulfill campaign promises. We’ll get to deep reform later.

Similarly, people whine that DOGE is not going to balance the budget by cutting $50 billion from USAID. That’s not the point. DOGE is going after small (by DC standards) amounts of money that have deeply pernicious effects. The money is the means, not the end.

No tax on tips

Economists are supposed to rise in a howl of disdain on this one. Well, the President made a campaign promise, wisely or no. Politicians deliver on campaign promises. So this has to be part of his proposal. Don’t just laugh, think.

We had a lot of fun with this when it came out. “Let’s ask Condi to swap half our salary for tips!” It actually might improve incentives a bit. If Condi handed out $1,000 tips at Hoover events, fellows like me might show up a bit more often!

But fun aside, let’s take this seriously. The devil is in the details. The tax economists in the administration and the tax-writing committees in Congress are pretty savvy. How will they implement this idea?

They surely are not going to let Hoover Fellows trade half their salary for “tips.” Surely, this offer will be limited by income. It will surely be limited to industries like restaurants, taxis and Ubers in which tips are traditionally are significant. They might limit it to people eligible for the lower tipped minimum wage, or those receiving no more than, say twice that wage as base pay.

I doubt they will allow tipped income to go undeclared. I suspect tipped employees will have to declare all income, and then receive a deduction for declared tipped income, subject to lots of conditions. This matters a lot, for a bunch of reasons that come up next.

Will the tipped income exemption apply to payroll tax or just the federal income tax? I bet only federal income tax — people will still have to pay social security, medicare, unemployment insurance and other taxes. That means tips have to be declared. For people who don’t earn much, social security and access to tax deferred retirement savings are good deals, so bringing their income into the official system is arguably worth paying a bit of taxes. (I know some people who worked off the books all their lives. They show up at 65 with no social security and having to pay premiums for Medicare.)

People with modest income don’t pay a lot of federal income taxes to start with. The basic marginal rate is 10% to $11,600, 12% to $47,150, and 22% to $100,525. But there are a bunch of deductions, exclusions, and tax credits before we even get there. My first google hit on this, the left-leaning Pew center, reports that the effective federal income tax rate is 2% to $30,000 and 4.2% to $50,000. “Oh, the budget, the deficit, the lost revenue” is completely unreal.

But taxes for people of modest income in the US are about something totally different — not how much the government takes but how much government support phases out with income.

The same Pew report calculates that the actual effective federal income tax rate for our typical waitress is more like negative 3 to 6%. We pay people through the tax code: the earned income tax credit, the child tax credit, the childcare tax credit, and many more. You only start paying the government anything around $50,000.

Moreover, all of these credits phase out with income. The actual marginal tax rate for people with low incomes — if you earn an extra dollar, how much do you get to keep — is driven entirely by how much of the various credits phase out as they earn more income, and has almost nothing to do with the federal taxes charged on income.

And the overall tax rate faced by people of modest means also includes social program phaseouts. If you earn an extra dollar, you lose some fraction of your food stamps, housing subsidies, medical subsidies, and hundreds more, down to the low-income bus pass. There are cliffs at which if you earn one more dollar you lose your apartment or health insurance.

Now you can see why the decision, do people have to declare tips (and will that be enforced) matters way more than whether people have to pay tax on tips. Do tax credit phaseouts and social program qualifications depend on tip income or not? They do now. My bet is that the actual tax proposal will say you still have to declare tips, it will offer a qualified deduction for tipped income, and that deduction will phase out with income. And that declared tip income will still trigger tax and entitlement phase outs.

Additionally, state and local income taxes may want to keep taxing tips (or pretending to), so they will require tips to be declared. It would be a mess if they weren’t declared for federal purposes but yes for state and local purposes.

(Incidentally, a pet peeve of mine is that actual income triggers tax credit phase out and social program payment reductions, but cash or in kind payments do not. Get a big tip for doing a good job cleaning a hotel room? We cut back your food stamps. Sign up for a section 8 apartment? No change. At least they should be treated equally, so as not to put the finger on the scales of how people seek to improve their lives.)_

I initially saw a second positive in exempting tips from taxes: it would encourage people to move away from cash. But once it’s declared, pays payroll taxes, and triggers credit and social program phaseouts, I doubt that incentive will change much. Still, pulling a bit more income into what is official, legal and declared sounds like a good thing.

And at this point, what’s the effect on the budget? Next to nothing.

The point was to help hard-working people. There are lots better ways to do that, as there are lots of better ways to reform the tax code. But the President campaigned on this one, so talk about that in the second round of reforms next year. In the meantime, relax.

No tax on social security

Again, the standard economic answer is to moan about the deficit, social security is already bust, etc. Yes but. It is a bit weird to give people social security and then take some of it back, no?

Background: Social security was marketed and conceived as a savings program, not a transfer program. That’s important for incentive effects. If for every dollar you put in to social security you get an extra dollar, plus some interest, the work disincentive of taxes is muted. Yes, you might not get as a good an interest rate as you could with private investments, but you still get something extra out of it. If it is a pure transfer program in which you pay taxes and someone else benefits, then the taxes just add to the work disincentive. That’s why social security taxes stop above a certain level of income, now $176,000. Social security benefits are capped at $61,000 per year, so high income people can’t get out an extra dollar if they put in an extra dollar. That’s why Medicare taxes used to be capped as well. A millionaire paying an extra dollar in taxes doesn’t get any extra Medicare benefit.

But the idea that we can fund our retirement and health care by paying taxes to support current old people, and then tax somebody else’s children to fund our own retirement, is obviously running against the reality of plunging birth rates. So, despite Roosevelt’s promises, Medicare and social security are gradually transforming into pure income redistribution programs, not trying to mimic savings.

Social security benefits were not taxed before 1983. The tax was introduced then as part of a first reform to stabilize its finances. Taxing social security has the same effect as reducing social security benefits with income, just like other social programs do. Removing the tax will remove that disincentive. And will make social security more expensive for the government. We’re in to the difficult tradeoff of all social programs: More income phaseouts save money but put huge marginal tax rates on those of lesser means, and as we see, fewer people work, work hard, try for better careers, and so on.

(Update: John Goodman explains how taxing social security benefits can imply a marginal tax rate of 80%. When you earn more, social security benefits are already cut. Then you pay taxes on the income and the benefits. Social security was already full of work disincentives.)

Social security needs fixing, with or without the kludgey tax on benefits. One way or another benefits will have to be reformed. My sad bet is that it will turn into a much more explicit transfer program. Like Medicare, the cap on social security taxes will be lifted. And an extra 5% or so will pile in to the upper end of marginal tax rates, and benefits will phase out more quickly with outside income. As we pile on work disincentives, we slowly will get less work. However, as it becomes more clearly a transfer program, it might become more clearly a program for the most unfortunate, with “middle class” people expected to save.

Ways out? Reducing taxes on social security could trade for income and asset phaseouts of benefits, or mild reforms such as indexing to prices rather than wages, higher retirement ages (or at least removing the strong disincentives to continue working), undoing the inclusion of federal workers, etc. Better, perhaps we can trade a large reduction in the taxation of savings and investment so that more people don’t need social security as a transfer program. The big social security reform should focus on making it financially possible for late middle age Americans to continue to work. Fix the incentives and you fix the money.

Bottom line, this is more nuanced than the standard moaning an gnashing of teeth. And let’s get going on the fundamental tax and social program reform!

No Tax on Overtime Pay

I have a hard time keeping my equanimity on this one, because the incentives are so awful.

The natural response is, instead of working 8 hours a day 40 days a week, ask your boss to work 15 hours a day two days a week and 10 the other day. Or just go on two 20 hour shifts.

It gets worse. There are already lots of laws that require companies and (especially) government employers to pay 1.5 or 2 times the hourly rate for overtime. Many jobs involve an elaborate game of getting overtime hours. Especially as one nears retirement with defined benefit plans keyed to the last few years of earnings, overtime shoots up. Eliminating taxes on overtime just adds to that artificial incentive.

Obviously, people are not as productive as they work longer and longer hours. It’s bad for health. It’s especially bad for women, people with families, people who have to care for elderly parents, people with children, and so forth. (My Hoover colleague Val Bolottnyy has a nice paper with Natalia Emanuel showing how overtime hurts women, even with a completely nondiscriminatory set of policies.)

If the President needs to keep a campaign promise, how about this: No federal income tax on overtime pay, with the usual occupation and other restrictions (no, Hoover Fellows can’t say that we’re “working” because we think about our work while we’re watching TV), but in return repeal all laws and regulations on overtime pay and hours. If we remove the mandatory 1.5 or 2 times higher wage on overtime, and remove the tax on overtime pay, the false incentive to bunch work might actually be reduced. The government might actually make money, as the incentive to work overtime could be reduced. Let hours go back to a flexible negotiation between the needs of a particular job for concentrated time, and the needs of workers.

Renewing the Trump Tax cuts

A no-brainer as the first step to comprehensive reform.

Why are we here? Because the 2017 personal income tax cuts were “temporary,” and are set to expire in 2025. Why did Congress pass temporary tax cuts? Because under current rules, tax changes are subject to green-eyeshade projections, and tax cuts can’t be forecast to blow out the budget over a 10 year horizon. So, you cut taxes “temporarily,” make the long-run budget promise look good, all the time counting on the future Congress not to dare to let the cuts expire once people get used to them.

Having a budget process, one that looks over reasonably long horizons, and that constrains spending to have something to do with taxes is a good idea. But you can see this is one more dysfunctional Washington dance. Those 2017 projections have noting to do with the current budget. Why? Because Covid hit. The Trump administration borrowed $5 trillion during Covid, and the Biden administration followed up with $6 trillion more in stimulus, “inflation reduction” ratholes, student loan forgiveness and more. Budget projections are always far off, just like other forecasts (inflation!), in part because we really don’t know how to measure behavioral changes well, and in part because something always happens. A pandemic hits, someone invents AI, …

If we want spending and taxes to automatically adjust over the long run, clearly forcing this silly dance of “temporary” tax cuts in response to horribly inaccurate green-eyeshade projections is a terrible idea. The German “debt brake” makes more sense — as debt rises, spending must be automatically cut, and taxes rise.

This is a more general problem. Regulations use hypothetical cost-benefit analysis when they’re passed, but never look back to how things are actually working out.

Anyway, here we are. I thought the corporate tax cuts a nice step in the right direction (0), and they cleverly hide some moves towards a consumption tax. I thought the personal tax-rate cuts also a small step in the right direction. 40% Federal, 13.5% state, 10% sales tax, 1% property tax, 23% federal + 9% state corporate tax, 40% estate tax add up for incentives. You may disagree.

But these are small changes at the edges, with much smaller effects on revenue than all of the fuss and bother suggests. I don’t get very excited about this minor up and down of rates within a huge corrupt Swiss cheese of a tax code. Coolidge cut the top marginal tax rate from 70% to 25%. Reagan from 70% to 28%. Federal revenue did not collapse. Now we’re talking. More later.

Adjusting the SALT Cap

SALT is not the return of the Roman empire’s tax on table salt. It is the deduction for state and local income taxes against federal income taxes.

There is some sense to the deduction. If the federal government charges 50%, and states also charge 50%, with no deduction, you have a 100% tax rate. Each of federal and state says “we’re only taking half, why does nobody work anymore?” If states charge 50%, and the federal government charges 50% of what’s left over, the overall rate is “only” 75%. As long as federal, state, local, sales, property, estate, savings, excise, and other taxes tax what’s left over the rate can’t exceed 100%. Most taxes work this way. For example, 10% sales taxes only apply to what’s left after high earners pay 40% federal and 13.5% state (CA), so they add only about 5%, not 10%, to the overall tax rate.

(Social program disincentives add up this way, which is what makes the whole disincentive that much greater than the sum of the parts. If food stamps and housing subsidies each phase out 30% with income, then when you earn an extra dollar, you lose 30 cents of food stamp benefits and 30 cents of housing benefits, not 30 x 0.7 = 21 cent of housing benefit.)

So, the deduction for state tax payments means that the Federal government only taxes income left over after states take their share. That helps to moderate the total marginal tax rate. That seems sensible.

But the problem is, the deduction gives states a huge incentive to raise taxes, especially on high earners who face high marginal federal rates. If the state of California raises income taxes on high earners, high earners pay 40 cents less federal tax for every dollar sent to California. So taxpayers everywhere else are offering a matching grant of 40 cents on the dollar for California to raise its taxes. And especially to make its taxes even more progressive.

The incentives are especially important for states, because high earners can move. The deduction substantially blunts the incentive to leave California when they raise taxes again.

Who does this benefit? Really only a small number of very high earners, who have not already left high-tax blue states, and who have complex finances so that they itemize deductions rather than take the standard deduction.

Suggestions: If President Trump wants to keep his campaign promise to help this demographic through fiddling with the tax code, just lower the top marginal rate for all the high earners everywhere. If we have to hide it, there are lots of other little tweaks he can offer that do not give such an awful incentive for bad government. Offer a SALT deduction for the first 5% of state income tax, and for states that keep spending under x% of GDP, but no more. Turn it around: Force states to allow a deduction for federal taxes in their taxable income. That gives the same result, but without the bad incentive. We long ago got around constitutional limitations on the Federal government bullying states this way. Make highway funding contingent on that provision.)

Closing the carried interest “loophole”

Again, not as obvious as it seems in either direction.

I have some money. You know how to cook. Let’s start a restaurant! But I don’t have that much money, and I’m worried that you won’t work hard. Rather than pay you a salary, why don’t I give you stock in the restaurant? If the restaurant does well, you can sell your stock and make a boodle of money. This is the essence of carried interest.

That seems like a good idea. What’s wrong? Well, if you make your money by selling the stock, you pay the capital gains rate rather than the ordinary income tax rate on the money. Thus, the government, by offering a lower capital gains rate, gives an incentive for us to structure the deal with stock rather than as wages. And the government gets less money, at least before any behavioral response to higher taxes is figured in.

“Close the loophole” you say. But then isn’t the lower taxation of capital gains the loophole? Why does the government do that? Well, for lots of good reasons! The optimal tax on capital gains, like all investment income, is zero. We should have a consumption tax. Get the rich at the Porsche dealer. For a century we’ve gone round and round on this, raising capital income taxes, only to find that they disincentivize saving, investment, and risk taking, and then lowering capital taxes again (corporate rate, corporate deductions, IRA 401(k) 526b etc savings sheltered from taxes, housing exemption, life insurance, step up of basis in estate taxes, etc. etc.)

Why do we tax investment income and corporations at all? Because if they are exempt, there are lots of ways to shift what is really wage income to capital gains. Incorporate yourself. The view that carried interest is a “loophole” suggests that this is just like me incorporating myself, charging Hoover for my services, and trying to pay the corporate tax rate.

But carried interest in the private equity, hedge fund, and venture capital world, really does involve sharing of risk and incentives. There is something to the “sweat equity” in place of money that partners put in, that is more like investment than working for a steady wage.

I guess it will take our financial wizards about 5 minutes to work around this. Instead of just giving you stock to cook for the restaurant, why don’t I sell you an out of the money call option on the restaurant? With $10 of your money as an “investment” I can give you the positive returns on $1,000 worth of stock. Then tell the IRS it’s a purely financial investment. The IRS will catch on, but our lawyers can stay one step ahead of them.

Also, before licking your chops at all the revenue, remember that a general partner’s ordinary income is someone else’s deductible expense for wages. I’m not enough of a tax expert to know how this goes. Corporations pay lower taxes than individuals, so a deduction for wages shifts money from corporate to personal tax rates. But partnerships may be pass-throughs taxed at the personal rate, so the general partner’s tax is fully offset by the partnership’s deduction. I’m not sure how it works, but at any rate you don’t get $1 per $1 of revenue here. (Thanks to a correspondent for posting this out.)

Bottom line: Not so clear as it looks, eh? This is just part of the endless cat-and-mouse game of trying to reclassify income as personal vs. corporate, wages vs. investment. They shouldn’t be taxed the same, but there are no bright lines and many clever lawyers. The right answer is to ditch the income tax altogether. Tax the rich at the Porsche dealer.

Tax cuts for made in America products.

I’m not sure what this means. We don’t tax products. Well, states charge sales taxes, but I don’t think a sales tax exemption for made in America is on the table.

I think this means lowering corporate tax rates to privilege US production. I’m all for lowering corporate tax rates, but not for protection. Still, this might have a lot of fun consequences. It would cause apoplexy around high tax countries especially the Europeans who tried to get a global minimum capital gains tax going. Foreign countries would pass zero corporate taxes for “made in Germany” or “made in China” products. Companies would then set up foreign subsidiaries so that each corporation only makes things in one country, and we have no corporate taxes at all.

So, not a great idea. Still, if you ask me to choose mercantilist policies between quotas, tariffs, and lower corporate taxes for value added in the US, I choose the latter as the least distortionary overall.

The next step

So, this is not the great tax reform/fix the budget/address the debt problem/fix social programs you were looking for. Of course not. This is a new Administration’s first quick actions to keep campaign promises and address the dance of “temporary” tax cuts. It is also not the “tax cuts for the rich and Trump’s billionaire buddies” that left wing rhetoric passes around.

The US does need that great reform. But this isn’t the time. Get through the first year, maybe build a record of success. Do well in the midterms and build the kind of mandate and congressional majority that doing things like eliminating the income tax and reforming social programs takes.

I am amazed at what the 20 or so young DOGErs are doing, that the Office of Government Accountability, various Inspectors General, the Office of Management and Budget, The Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs, regular audits, congressional inquiries and more have not been able to do. The rot they uncovered and publicized at USAID in a few days is astounding. Now, once they’re done with military procurement, I can’t wait to see what happens when they crack open the tax code. And then when they crack open social programs. As their exposure of what’s going on at USAID will necessarily lead to major reforms, a wide open book on what’s going on with taxes and social program will help that effort tremendously. That could be the path to, finally, a major reform. I admit a lot of optimism lies in this scenario.

(This post resulted from a short interview I did for Tom Bevan’s Real Clear Politics podcast, that you might enjoy.)

This article is definitive proof that people who are,brilliant in one area can be really stupid in another. Professor Cochrans ability to dissect the tax code is remarkable. His comments on DOGE and AID are simply ideological nonsense. I am not surprised that 20 young thugs given the right to perform illegal acts, given the right to threaten civil servants and given a broad ok by someone worth $400:billion can do more damage quickly than people forced to act legally. And I’d live to see Professor Cochran list the ‘rot’ he says has been discovered at AID. AID’s annual budget is about $25 billion. Find $250 million of rot. Not programs you don’t like - you may not like food aid to areas hit by famine, but that’s not rot.

„DOGE is going after small (by DC standards) amounts of money that have deeply pernicious effects“ Please give an example of a „pernicious effect“ that DOGE has stopped. HIV vaccinations? Grain sales?