Swiss reflections

I’m just home from Switzerland, where I gave the Karl Brunner Lecture. It is always eye opening to travel and see how other countries do things, and leads me to question basic assumptions.

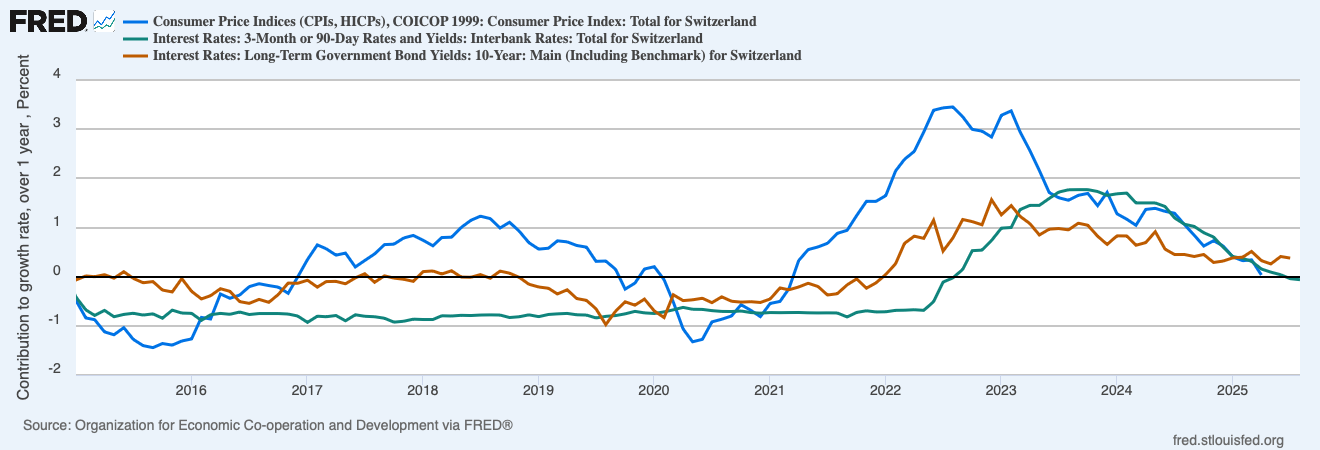

Swiss inflation barely exceeded 3% in the post-pandemic surge, and is back to zero. Interest rates are also back to zero.

The SNB balance sheet is huge, at 854 billion CHF, coincidentally exactly the same as GDP. Imagine the Fed had a $30 Trillion balance sheet, not “merely” the $6.5 trillion that people complain about.

You might think Switzerland is on the vanguard of a return to zero bound, zero rates, secular stagnation, immense quantitative easing. You would be wrong. Switzerland’s central monetary problem, at least as perceived by the Swiss, is too much of a good thing. The rest of the world wants its currency and debt. They want to offer the Swiss “exorbitant privilege.” The Swiss are uninterested. (When the conversation turned inevitably to stable coins, nobody wanted a Swiss franc stable coin. They would have to issue more debt or reserves to do it, and more demand for their debt is the last thing they want.)

The Swiss franc keeps climbing. Note the upward spike. Switzerland is the only country I can think of that has ever had exchange rate intervention fail in the upward direction. The rest of the world wants to send Switzerland Porsches in return for printed money. No thank you say the Swiss.

The SNB balance sheet lists 754 billion Swiss francs in “foreign currency investments” out of 854 billion total assets. The SNB intervenes to manage the exchange rate, as well as to set an interest rate target, buying foreign assets to try to hold down the exchange rate. This is unlike the US, in which the Fed eschews foreign currency intervention and the Treasury is nominally in charge of exchange rates.

This reality challenges the conventional doctrine that countries can’t simultaneously have a monetary policy and exchange rate policy. One instrument, the money supply, one outcome, either the price level or the exchange rate, said the classic theory. But the opposite is frequently practiced, and with an interest rate target the basic proposition is not so clear. There must be a theory on this, and let me know in the comments what I’m missing. (I’m not that good at international macro). I can see a model with an interest rate target in which the exchange rate target fills the indeterminacy gap the same way that FTPL does. I can also see the usual “frictions” that rationalize interest rates and QE as separate policies.

My jaw dropped, though, in thinking about the fiscal and independence implications of this balance sheet and central bank exchange rate intervention. The standard view in my circles is that the Fed’s big balance sheet of long-term treasurys and mortgage backed securities ventures in to fiscal policy and credit allocation, and hence poses a threat to the Fed’s independence. So, the Fed ought to reduce its balance sheet, and move to holding exclusively short-term treasurys. Here we have a balance sheet three times larger, relative to GDP, and invested in foreign bonds and even stocks. If the exchange rate rises, or if foreign stocks fall, the SNB will take big losses. One could also say that the SNB is running a giant leveraged hedge sovereign wealth fund on behalf of the Swiss taxpayer.

All my inquiries on this point fell flat. Nobody is worried about the independence consequences of portfolio losses. In part, the SNB is actually owned by stockholders, mainly the Swiss Cantons. They receive regular dividends. And they seem happy with what the SNB is doing and willing to suffer lower dividends should the SNB lose money.

Liabilities are 74 billion banknotes, 420 “Sight deposits of domestic banks” which I think means reserves, and only 23 “foreign currency liabilities,” so the exchange rate exposure is real. Listed under “equity” is 115 “Provisions for currency reserves” which I think means a retained profit that can be seamlessly reduced if there are asset portfolio losses, called provisions for future losses in other central banks, and the key -53 billion “distribution of profit” to its shareholders. 80 “annual result” I don’t fully understand, but I suspect that is retained profits that might be distributed in future distributions, as opposed to retained profits that will buffer future losses. The same website has a long “profit distribution agreement,” spelling it out.

So, independent central banks can have a large balance sheet with lots of foreign exchange and equity risk. It takes a political system that supports the central bank’s “independent” decisions, even with large fiscal effects.

Of course, I only heard the SNB’s view on this. There was one loud critic at my talk. We’ll see how happy everyone is if foreign stocks and bonds fall in value, the Swiss franc skyrockets, amid a global recession, and the SNB’s shareholders are faced with the actual big losses.

Why did Switzerland have so little inflation, and why did inflation go away so quickly? Well, if you’re a blog follower you know I think the recent inflation in the US and Europe came from unfunded fiscal deficits.

Here is recent Swiss fiscal policy. The worst deficit in the pandemic was under 20 billion, or about 3% of GDP. The US by contrast hit 25% of GDP deficit. The budget went quickly back to balance — total balance not just primary balance. Debt is a tiny 16.8% of GDP. Yes, 16.8, not 168. The SNB literally could not provide 420 billion reserves by buying domestic government debt.

Balance is not just accidental. Switzerland has a constitutional “debt brake,” passed by referendum, that requires cyclical budget balance. They seem in no hurry to jettison it, as the Germans did when a few percent of GDP extra defense spending needs inconvenience half of GDP social spending.

So, adding it all up, it’s if anything a puzzle that the Swiss had any inflation at all. The deficit was very small. The debt was tiny. And, most of all, the “debt brake” assures people that the debt will be repaid. As I think about fiscal inflation, this confidence that debt will be repaid is the key to running even large deficits or large debts without inflation. What inflation there was seems imported: higher nominal prices by trading partners that the SNB did not want to see transmitted to even higher nominal exchange rates.

I see the outlines of an interesting FTPL description of Switzerland, or at least the theoretical possibility of a similar country. Fiscal policy is passive, and promises via a debt brake to always repay debt. The central bank has an interest rate target and a large balance sheet of foreign assets. The real value of the foreign assets backs currency and reserves, so FTPL applies as real value central bank liabilities = real value of central bank assets. The interest rate target and exchange rate target then set the level of nominal liabilities (the B). The central bank also changes the exchange rate risk of the balance sheet, buying and selling domestic vs. foreign debt.

We could alternatively interpret a debt brake and exchange rate intervention as a joint “active” fiscal policy. The government commits to pay off accumulated deficits, but not to pay off rises in the value of debt caused by unexpected deflation. The accumulation of foreign currency assets then implements this commitment that deflation and exchange rate appreciation will result in less fiscal surplus.

I just made this up and do not know if it makes sense once one writes down the equations. Open economy fiscal theory of monetary policy is low-hanging fruit.

I am also softening a bit my standard economists’ disparagement of the school that says trade deficits and exorbitant privilege are bad, such as the Mar-a-Lago Accord and Stephen Miran’s essay. After all, the Swiss don’t want exorbitant privilege either.

Your mother told you that it is good to save. That’s what running a trade surplus and capital account deficit means to a country: Work, earn more than you consume, accumulate foreign securities, so that in a rainy day or when you get old you can turn it around, cash in those chips, and enjoy consumption without working so hard. Borrowing to finance consumption is dangerous. Trade deficits that finance consumption mean eventually turning around and working hard to put things on boats in return for our pieces of paper, or at least promising to do so.

Now, trade deficits used to finance investment in high-productivity projects are fine, just as borrowing to invest in a good business is a good idea. The main problem with our trade deficits is that they financed government spending which subsidized consumption. Still, mercantilist disparagement of a persistent overall trade deficit is not totally misplaced.

I also was struck by the “Cross of Gold” paper by Davis Kedrosky and Nuno Palma.

As late as 1750, Portugal had a high output per head by Western European standards. Yet just a century later, Portugal was this region’s poorest country. In this paper, we show that the discovery of massive quantities of gold in Brazil over the eighteenth century played a key role in the long-run development of Portugal. The country suffered from an economic and political resource curse. A counterfactual based on synthetic control methods suggests that by 1800 Portugal’s GDP per capita was 40 percent lower than it would have been without its endowment of Brazilian gold.

Gold being the money of the 1750s, Portugal got to print the world’s money. It used that exorbitant privilege to finance consumption goods from the rest of Europe. Doing so, Portuguese industry and knowledge languished.

Again, it’s not so easy as the Mar-a-Lago crowd would have it. Trade deficit financed investment also needs good high marginal product projects, which Portugal might have lacked, and the US might have lacked too. And the Mar-a-Lago interventions seem unwise to me. Figure out why the US is consuming and not investing seems the answer.

But it was brought home to me that the Swiss do not want to print the world’s money and rake in consumption goods either, and I cannot say they are unwise for doing so.

Of course, the first thing on everyone’s mind is “why in the world is the US imposing a 35% tariff on us?” to which I could only apologize.

Updates:

A colleague sends me this article from 1974, when the Swiss imposed a 12% tax on foreign bank accounts. Even taxing foreign holdings to tamp down the exchange rate, reduce capital inflow, is not new.

A nice substack on “why is Switzerland so rich?” Answer: free markets.

"The main problem with our trade deficits is that they financed government spending which subsidized consumption." You don't say. That's the whole point behind Trump's tariffs, which are 80% or so taxes on consumption, and which are aimed at incentivizing more domestic investment. Some of us have been beating that drum for a while, while the "free trade" fundamentalists have ignored the financing side of the BoP (See Gramm and Boudreaux in the WSJ). It would also be good to reduce out of control government spending and grotesque fiscal deficits which induce the "need" for borrowing from foreigners and/or printing money.

You might check some of these substacks... Switzerland's been fascinating to watch in recent years. Yes, totally the exception. https://substack.com/@swissmacro . You might know him "Stefan Gerlach writes on monetary policy and central banking, occasionally with a historical perspective. He is Chief Economist at EFG Bank in Zurich and was Deputy Governor of the Central Bank of Ireland."