Stagnation and hope

A European friend writes (slightly edited) a report from a conference.

The conference was largely about Germany’s economic challenges. You do not believe the burden imposed on firms via EU and German regulations in recent years. The aim of such regulations is to protect personal data, to protect birds, to protect trees in the whole world, to protect working conditions and avoid child labor in the world, force firms to have complete carbon emission accounts, including carbon emission from all the input they import from the whole world, to ensure cyber security, including of global firms that provide inputs.

I hear about firms that want to (continue to) import chocolate, coffee beans, meat into the EU, but cannot do so, as their traditional suppliers from Africa or Latin America cannot prove that the land they use to produce agricultural inputs for such product was not cleared of woodland withing the last I think 4-5 years.

This is absolutely Kafkaesque. Everything is about morality, with very short-term thinking. every lobby group seems allowed to push through its special interests, nobody seems to do a reasonable cost-benefit analysis, before such laws, regulations are drafted and voted.

As a consequence China and Russia in the future will do most business, say with Africa. The working conditions and child labor will mostly worsen due to this. Europe will import EVs and batteries from China, produced with input from child labor in Africa/ Congo and forced labor by brutally suppressed Uighur who forced to live in camps in the Uighur region of China. But this is ok, as the Chinese firm is not located in the EU.

There is good news in all this. Europe is waking up to its stagnation. Conferences like this happen. Mario Draghi wrote his report, good on diagnosis, hair of the dog on cure (more industrial policy), but at least focusing on the problem.

Every bit of economics says that the common market, the European Union, and the euro should have boosted European economies. Why should one, big, integrated market languish 30% or so behind the US, and now fall behind? The hard to quantify drag of over regulation is an obvious answer.

Related, I found Scott Alexander’s notes from the Progress Studies Conference illuminating. (HT Marginal Revolution.)

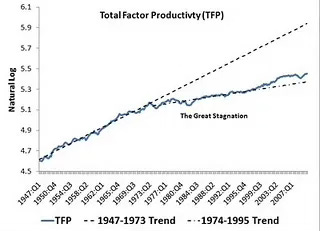

Progress (as measured by things like total factor productivity) was fast for much of the early 20th century, then slowed around 1970. Nobody knows why; theories include shifting social attitudes, over-regulation, or simply exhausting the potential in a few big inventions like electricity and mass production. This slowing was a great historical tragedy: if progress had continued at pre-1970 rates, we would be twice as rich today. We call the ensuing period the Great Stagnation. There was plenty of innovation in computers (“the world of bits”), but real physical goods (“the world of atoms”) stayed disappointingly similar. Our great-grandparents grew up in a world of horse-drawn carriages and lived to see the moon landing. We grew up in a world of cars and jumbo jets, and live in it still.

(the post has some later doubts about this graph.)

But Tyler Cowen has declared the Great Stagnation provisionally maybe starting to be over. This is a bold pronouncement; official statistics are as dull as ever, and Progress is a field where going off vibes leads you astray. Still, advances in AI, solar, space, and biotech seemed impressive enough that he thought it represented a phase change.

That is, if we can get the permits.

The solar vs. nuclear debate for power abundance is fun, but I don’t really care who wins. Centrally, both sides offer a vision of energy abundance vs. the freeze-in-the-dark energy scarcity that dominates policy discussions, even among economists.

Everyone agreed that we should have 100x as much energy per person (or 100x lower energy cost), that we should simultaneously lower emissions to zero, and that we could do it in a few decades. The only disagreement was how to get there, with clashes between advocates of solar and nuclear…

Why is solar improving so quickly? Humanity is very good at mass manufacturing things in factories. Once you convert a problem to “let’s manufacture billions of identical copies of this small object in a factory”, our natural talent at doing this kicks in, factories compete with each other on cost, and you get a Moore’s Law like growth curve. Sometime around the late 90s / early 00s, factories started manufacturing solar panels en masse, and it was off to the races….

In the 1960s, nuclear was supposed to bring the amazing post-scarcity Jetsons future. It could have brought the amazing post-scarcity Jetsons future. But then regulators/environmentalists/the mob destroyed its potential and condemned us to fifty more years of fossil fuels. If society hadn’t kneecapped nuclear, we could have stopped millions of unnecessary coal-pollution-related deaths, avoided the whole global warming crisis, maybe even stayed on the high-progress track that would have made everyone twice as rich today. …

The pro-nuclear side insisted they also had practical arguments. Look at the top graph again. Between 2010 and 2019, nuclear cost per megawatt-hour increased from $96 to $155. In fact, nuclear has been increasing ever since the ‘60s, when it cost about $20 (in current dollars). This is proof of concept that nuclear can be much cheaper than it is now. If we did everything right - got really good regulations, innovated hard, switched to the most promising type of nuclear reactor - we could not just get the cost back down to $20,

Stop just a second. We usually think that technology can’t regress — that we can do now anything we used to know how to do. Nuclear power used to cost $20 per megawatt-hour. Edit copy, edit paste. Economists are optimists, used to studying growth and innovation. Perhaps a study of regress is appropriate to our age.

but go even lower - as low as $1 per MWh within a decade or two. That’s much cheaper than solar, which is currently $68 per MWh.

(this would probably look like small modular reactors mass-produced in factories, to take advantage of the same factory-scaling trend that helped solar. Surprisingly, the best regulatory climate for this appears to be the UK, although it’s still very bad and there’s a long way to go.)

This last point is worth stressing. Nuclear plants today are extremely custom-built, on site, like a LA mega-mansion, whose owner keeps sending in change orders. Oh, and factory built housing is also illegal in much of the US.

But really, the solar vs. nuclear debate is not technological. The debate is whether reform of the Nuclear Regulatory Commission or reform of the National Environmental Quality Act (and, looming tariffs and quotas against cheap solar panels) will win:

Over-regulation was the enemy at many presentations, but this wasn’t a libertarian conference. Everyone agreed that safety, quality, the environment, etc, were important and should be regulated for. They just thought existing regulations were colossally stupid, so much so that they made everything worse including safety, the environment, etc. With enough political will, it would be easy to draft regulations that improved innovation, price, safety, the environment, and everything else.

For example, consider supersonic flight. Supersonic aircraft create “sonic booms”, minor explosions that rattle windows and disturb people underneath their path. Annoyed with these booms, Congress banned supersonic flight over land in 1973. Now we’ve invented better aircraft whose booms are barely noticeable, or not noticeable at all. But because Congress banned supersonic flight - rather than sonic booms themselves - we’re stuck with normal boring 6-hour coast-to-coast flights. If aircraft progress had continued at the same rate it was going before the supersonic ban, we’d be up to 2,500 mph now (coast-to-coast in ~2 hours). Can Congress change the regulation so it bans booms and not speed? Yes, but Congress is busy, and doing it through the FAA and other agencies would take 10-15 years of environmental impact reports.

Supersonic flight and nuclear power are two great economic counterfactuals. Like the Chinese emperors of the 1400s who abandoned ocean sailing, our society abandoned two great technologies. Who knows what the world would look like today with abundant power and widely developed supersonic airplanes — and all the technology that would have followed from those two?

Supersonic flight is particularly interesting. The anti-nuke business was a big popular cause; the anti-Vietnam war left moved on to that in the late 1970s, before moving on to today’s passions. Banning supersonic flight, rather than banning sonic booms was the key mistake. And doing it by law rather than regulation was a second mistake. (Finally, I have something nice to say about the administrative state.) Both make investing in low noise (and next, low drag and less fuel intensive) supersonic flight a losing proposition.

This fact offers a lot of optimism. Small changes in the nature of regulation can have huge effects on its adverse consequences. We don’t have to upset many big constituencies, we just have to regulate a little bit smarter. Regulate outcomes rather than methods. (The same point comes up in building codes.)

… The average large solar project is delayed 5-10 years by bureaucracy. Part of the problem is NEPA, the infamous environmental protection law saying that anyone can sue any project for any reason if they object on environmental grounds. If a fossil fuel company worries about a competition from solar, they can sue upcoming solar plants on the grounds that some ants might get crushed beneath the solar panels; even in the best-case where the solar company fights and wins, they’ve suffered years of delay and lost millions of dollars. Meanwhile, fossil fuel companies have it easier; they’ve had good lobbyists for decades, and accrued a nice collection of formal and informal NEPA exemptions.

Even if a solar project survives court challenges, it has to get connected to the grid. This poses its own layer of bureaucracy and potential pitfalls. The most memorable statistic from this part of the presentation: over the past few years, Texas has approved more solar power than every other state combined, and more wind power than every other state combined, and more renewable-friendly batteries than every other state combined. This isn’t because Texas is especially environmentalist. It’s partly because Texas has its own grid with less bureaucracy, and partly a general libertarian attitude that lets renewable businesses expect a fair deal from the government.

I was aware of NIBYs and no-growthers abusing NEPA, but not how competing big business does so.

Another story about how tiny details in regulation are the straw that breaks the Camel’s back:

Nuclear is in an even worse situation, as you can tell from the recent $96 → $155 price rise mentioned above. This is partly because - as Matt Yglesias writes - nuclear plants are held to an “As Low As Reasonably Achievable” safety standard. Suppose an company invents a nuclear plant which is twice as cheap and twice as safe as existing models. They might like to try selling it for a bit below the cost of existing models, then pocket the profits. But the regulator will say that because it’s cheap, they have more money to spend on safety, and demand safety improvements until it costs just as much as existing models (even though the new model was already twice as safe). This declares it impossible by fiat to ever make nuclear any cheaper, which means we keep using coal forever, even though coal is much more dangerous.

The solution would be to enshrine into law some specific safety standard for nuclear - maybe 1000x safer than coal power. Then inventors can start there and make things cheaper, instead of having every efficiency gain get eaten up by more safety regulation. Then more people would switch from coal to nuclear, and we would be even safer and have cheaper electricity and have lower emissions.

It’s popular to blame environmentalists and government regulators for this, and they do deserve part of the blame, but the speakers at the conference urged us to also blame existing nuclear companies, who lobby the government to add more and more burdensome safety regulations so they can charge more and keep out competitors. Again, this isn’t a war between economy-boosters and sympathetic activists who want some other good. It’s just dumb laws and regulatory capture hurting everybody.

Never count on existing business to be against regulation or for free markets.

Scott goes on to cover doubts about my first graph, but before you get too tired I want to pass on the quietly optimistic message

Congress understands the problems with NEPA and is at least considering making life easier for the solar plants. Suddenly everyone’s a YIMBY. The first small modular nuclear reactor has been approved.

But more than that, there’s suddenly awareness. It might seem like nothing could be more obvious than the idea of “wait, we fell off this growth curve and now we’re twice as poor as we need to be, maybe it’s all the growth we’re blocking”. Or “wait, we basically made it illegal to build houses and now the American dream of homeownership is critically endangered”. ….

It feels like the United States, after a fifty-year binge on over-regulation, has woken up, wiped the vomit off its chin, noticed it’s lost half its net worth, and started to consider doing something else. ..

And Europe too.

It’s interesting that with Great Stagnation meeting Progress and Abundance, our presidential campaign has been dominated by such trivial economic issues. Neither candidate talks about fixing these gargantuan gaping wounds. Rather each adds rather small new initiatives — subsidies for small business, subsidies for home buyers, tariffs here and there, tax rates up or down a few percentage points. Their rhetoric is apocalyptic, but their proposals are those of a self-satisfied society with a perfectly running economy needing only a little tweak here and there to help small constituencies. Perhaps 2028 will feature the Abundance Agenda candidate.

(Update: Saying anything about Presidential politics is dangerous, and my inbox is already overflowing… My comment was only about campaign rhetoric. Even in the next four years there is hope. The Trump team includes many free-market deregulators. See the America First economic advisers for example. The YIMBY movement and occupational licensing reform are strong among democrats. The windmills and solar panels crowd have figured out they need NEQA reform, and even the Sierra Club now reluctantly can say the word “nuclear.”)

My quibble on energy is if you read Robert Bryce's substack, measuring on cost per kilowatt might not be the ultimate measure. Energy density might be a better measure along with the cost to produce energy, and solar has no energy density. Nuclear is incredibly dense. This means a little uranium can power huge swaths of the economy where solar would take gigantic solar farms to do the same---and the negative externalities of solar are far greater than nuclear.

This piece illustrates the law of unexpected consequences when government interferes with markets, with the corollary that the costs (unexpected consequences) are positively correlated with the size of the interference (large interference --> high economic costs):

> Between 2010 and 2023, US GDP grew by 34%, while the EU grew by 21%.

> In 1990, US GDP per capita was 16% higher than EU; by 2023, the difference had doubled to more than 30% (depressing and damaging)

Germany's voters may have to confront these stark statistics and start a GEREXIT petition. Back to the US, there is abundant evidence that nuclear energy's benefits make economic sense -- the next election will determine whether we continue down the path more trillion dollar IRA programs or start imposing more rigid cost-benefit analysis to emerging rules and regulations spewing like smokestacks out of DC, cuz that is what they know how to do...