This is a paper I wrote for the 2024 Bank of Japan Institute for Monetary and Economic Studies Conference. pdf here if you prefer that format.

Inflation, Monetary and Fiscal Policy, and Japan

1. A perfect monetary policy outcome

The standard narrative for Japan says that an asset price “bubble” burst, financial turmoil brought down the economy, the Bank of Japan lowered interest rates but got stuck at zero. A “liquidity trap” or “deflation trap” then set in, and despite valiant efforts of fiscal stimulus, unconventional monetary policy (QE, forward guidance, negative rates, long term bond price setting), Japan remained mired in secular stagnation for 30 years. Only with the arrival of the covid “supply shock” did inflation unanchor from the perverse no-price-change psychology that had set in, finally allowing Japan to return to a healthier 2% inflation which will at last allow a return to growth. (For an eloquent exposition, see Shinichi 2024.)

I offer—really remind us, as the observation is not new—an alternative narrative. In this narrative, the BoJ and monetary affairs is not to blame for 30 years of lost growth, which may be good news. But the BoJ is also much less powerful to be the engine of revitalized Japanese growth, which is not always welcome news to a central bank.

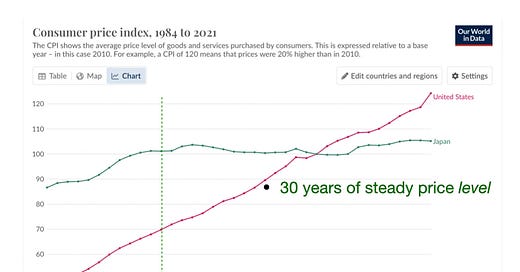

I start with a radical claim. Japan has, for 30 years since the mid 1990s, had the most perfect monetary policy outcomes the world has ever seen.

Not only has there been no inflation, the price level has been steady. When the US Congress or the EU commission said unto the Fed and the ECB, “price stability,” this is likely what they had in mind, not 2% inflation, with the price level forgetting past mistakes.

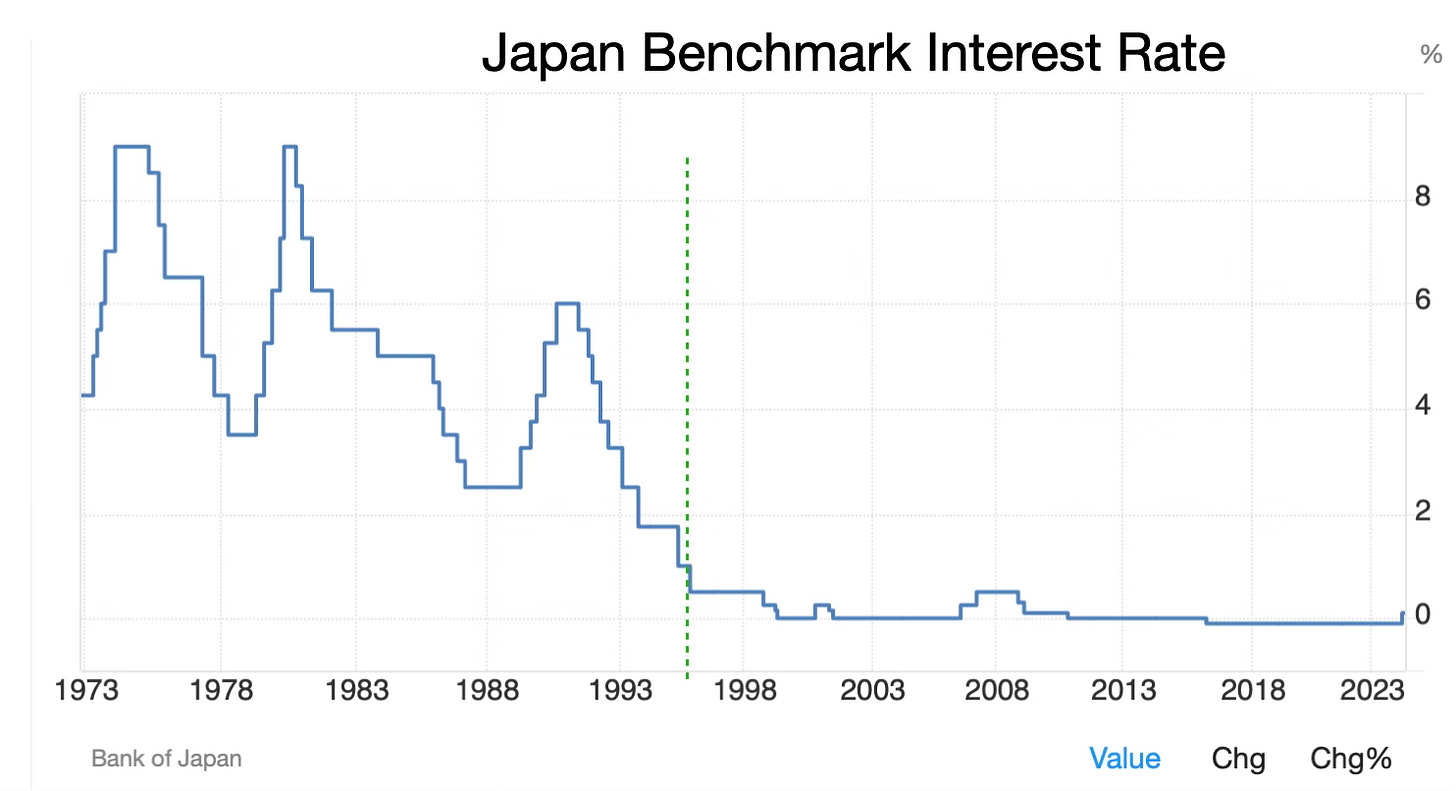

Interest rates have been zero, as Milton Friedman’s optimal quantity of money recommends. At zero interest rates, people waste no time economizing on cash. More importantly, financial institutions do the same. There is no incentive to create run-prone interest-bearing money such as overnight repurchase agreements.

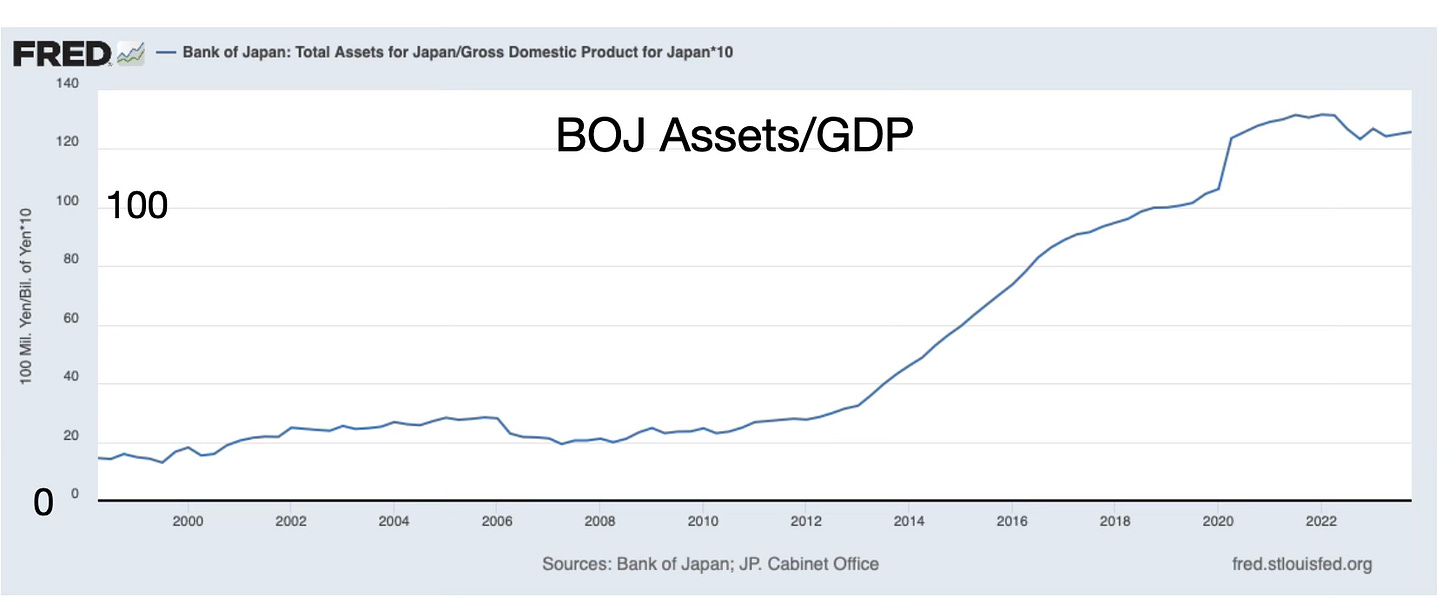

Japan is satiated in liquidity. The BOJ balance sheet is over 100% of GDP. Money is oil in the car. It’s optimal to drive the car full of oil, if you can do it without causing inflation. Japan has done so.

A steady price level was not the announced policy of the Bank of Japan, nor the desire of the many American economists who came before me to criticize it. But, as the great Mick Jagger once proclaimed,

The outcome has been nearly perfect even if that was not officially intended.

The stagnation narrative

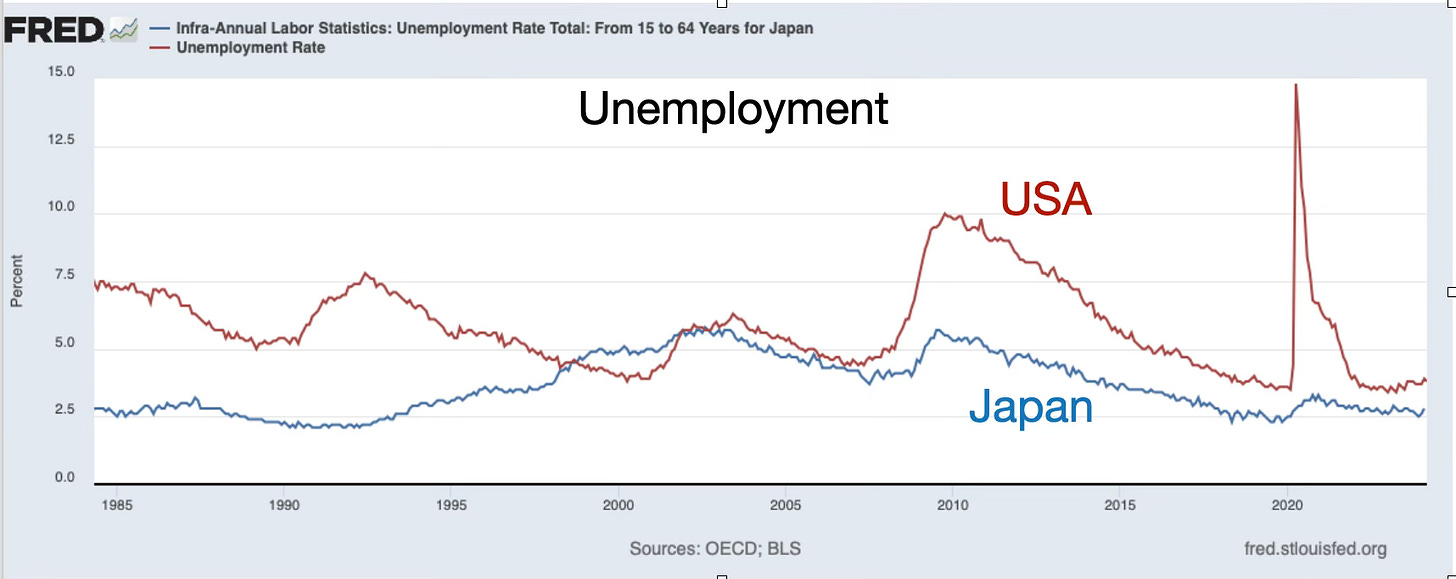

What of the supposed 30 years of stagnation supposedly brought on by the deflationary pressure of the zero bound? On basic principles, monetary non-neutrality doesn’t last 30 years. If there is a 30 year growth problem, it’s a growth problem, microeconomic not macroeconomic. The recent inflationary episode in the US shows that sticky price nominal-real interactions happen on the time scale of a year or two, not thirty. There is no sign of perpetual lack of demand. Japan’s unemployment rate has been below that of the US the entire time.

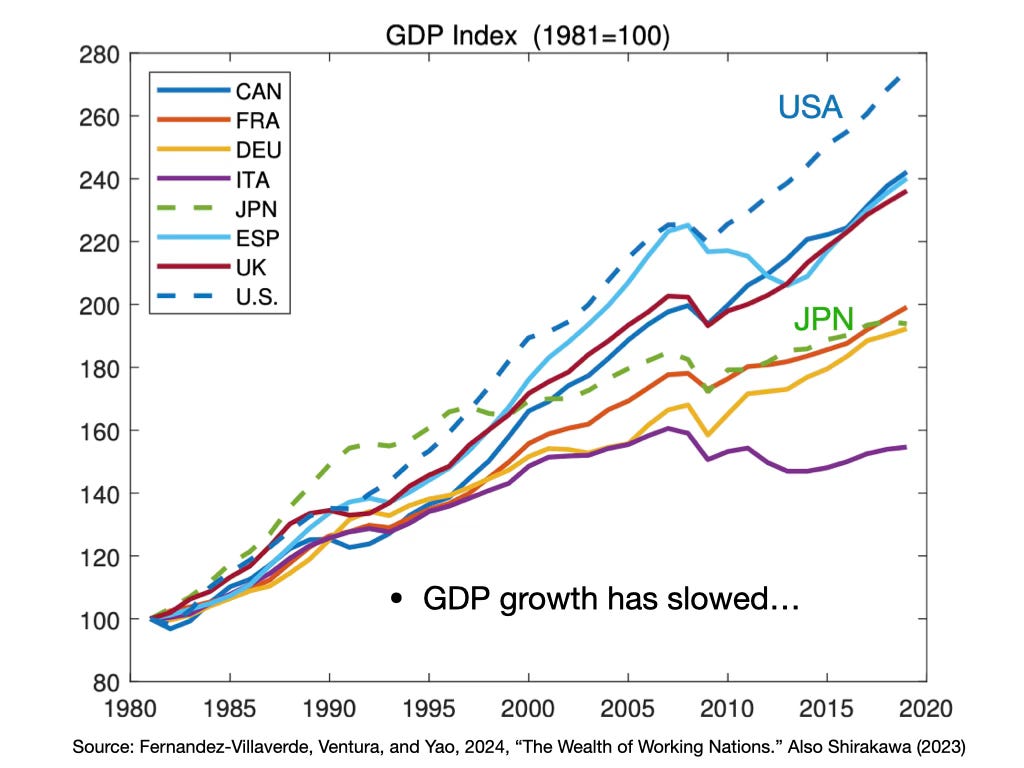

Yes, Japan’s GDP growth has slowed, showing less growth than the US. But Japan’s GDP per working age person has grown faster than in the US. (Shirakawa 2023; Fernández-Villaverde, Ventura, and Yao, 2024.) Japan’s total GDP is growing slowly simply because its population is declining. Perhaps Milton Friedman (1968) should have extended his list of things that monetary policy cannot do. Monetary policy cannot create long-run growth. And monetary policy certainly cannot induce people to have babies!

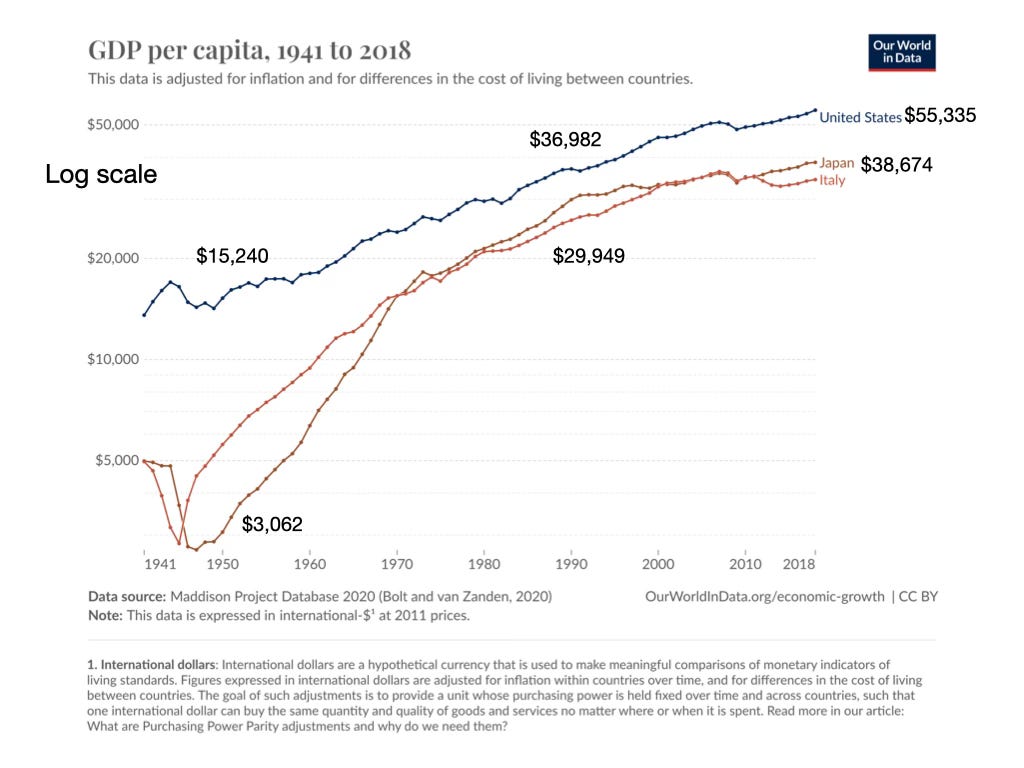

I do not mean to say all Japanese economic policy is perfect. After WWII Japan had a rapid period of catch-up growth. That hit an inflection point in 1973. Japan’s per-capita GDP came closest to the US in 1991, peaking 16% below the US. On either per capita or per working age person basis, Japan got stuck substantially below the US level of output per worker, and remains in the general territory of Italy. (I use GDP per capita here and below because I don’t have easy access to the GDP per working age person data.) Japan’s productivity growth has been slower than the US (which itself has slowed down). But productivity growth is not a lack of demand problem.

With a well-educated, industrious, and thrifty population, homogenous society, the lack of pockets of isolated poverty and dysfunction, and general cleanliness, safety, and order that stupefy American tourists, Japan should have passed the US, as Singapore has. Still, Japan is 29th on the World Bank’s ease of doing business index, well behind the US 6. The easiest way for Japan to lower its debt to GDP ratio is to raise its GDP. And that takes microeconomic reform, not macroeconomic machination.

Growth Economics is clear: Each country catches up to the productivity frontier, until its level of microeconomic inefficiency stops it. That too, however, is something monetary policy can do nothing about.

The “bubble?”

The end of catch-up growth suggests an answer to another common complaint about Japan, that it had a “bubble” and 30 year slump as a result. The transition from “catch up” to “frontier growth minus level inefficiency” can cause prices to crash, not necessarily the other way around.

Suppose a country starts with 1/5 of the US GDP per capita. It enters a period of “catch-up” growth, adopting successful “frontier” institutions and rapidly investing. Eventually, however, “catch-up” growth must end. The formerly poor country reaches the technological frontier, minus whatever “level” effect its microeconomic inefficiencies allow it. After that, it grows only at the “frontier” growth rate.

It might get stuck in the “middle income trap,” like Brazil, 75% below US GDP per capita. It might continue, as Germany and Western Europe did, reaching 20% below US levels before plateauing. It might reach the US level. The US hardly has perfect microeconomic institutions, and I estimate it’s easily possible to reach 40% or more above US levels by adopting free-market growth-oriented policies. Singapore hints at that possibility, rising 20% above the US. (I leave out the darker possibilities, of then sinking into zero growth sclerosis like Italy, or disasters like Venezuela and North Korea.)en

While the country keeps growing at high “catch-up” rates, everyone (except the usual chorus of doomsaying US commentators) knows the fast growth will stop at some point, but nobody knows for sure when. Asset prices reflect the possibility that growth keeps going. When the country hits its microeconomic barrier, and starts growing at the frontier rate, asset prices no longer include the option for greater growth, and collapse.

To make this story concrete1, let the frontier growth rate be g_l and the high catch-up growth rate be g_h, and think of the price of a consumption claim. The price-consumption ratio in the low-growth state is

where r is the expected return, the same for all countries. While the country is growing quickly, each year there is a probability lambda that growth will revert to the frontier growth rate. I work out in the appendix that the price-consumption ratio while the country is growing quickly at g_h is

For example, with r=4%, g_h=8%, g_l=2%, and lambda=5% (20 years of growth on average), we have pc_h/pc_l = (4-2+5)/(4-8+5)=7. Stock prices with high growth are 7 times higher than with low growth. When the economy finds its limit and starts growing at the frontier rate, the stock price falls to one seventh its original value! With a smaller 6% per year catch-up growth rate, we have pc_h/pc_l = (4-2+5)/(4-6+5) = 7/3=2.3. The stock market still falls in half.

Summary and regret?

In sum, I offer a plausible counter-narrative, based on simple growth theory rather than complex Keynesian macro. Japan switched from catch-up growth to frontier growth, at a level reflecting microeconomic inefficiencies typical of Europe. Asset prices fell. Interest rates hit zero and the inflation rate stopped. The BoJ was handed a golden opportunity, which it took. The zero interest, steady price level monetary Nirvana is hard to get to. To get there directly, a central bank has to wait out adverse temporary dynamics. Alan Greenspan talked about getting to the zero inflation ideal opportunistically in this way. Japan then lived 30 years of optimal monetary policy outcomes. And the real economy continued to follow real, “supply” driven forces, as it must in the long run.

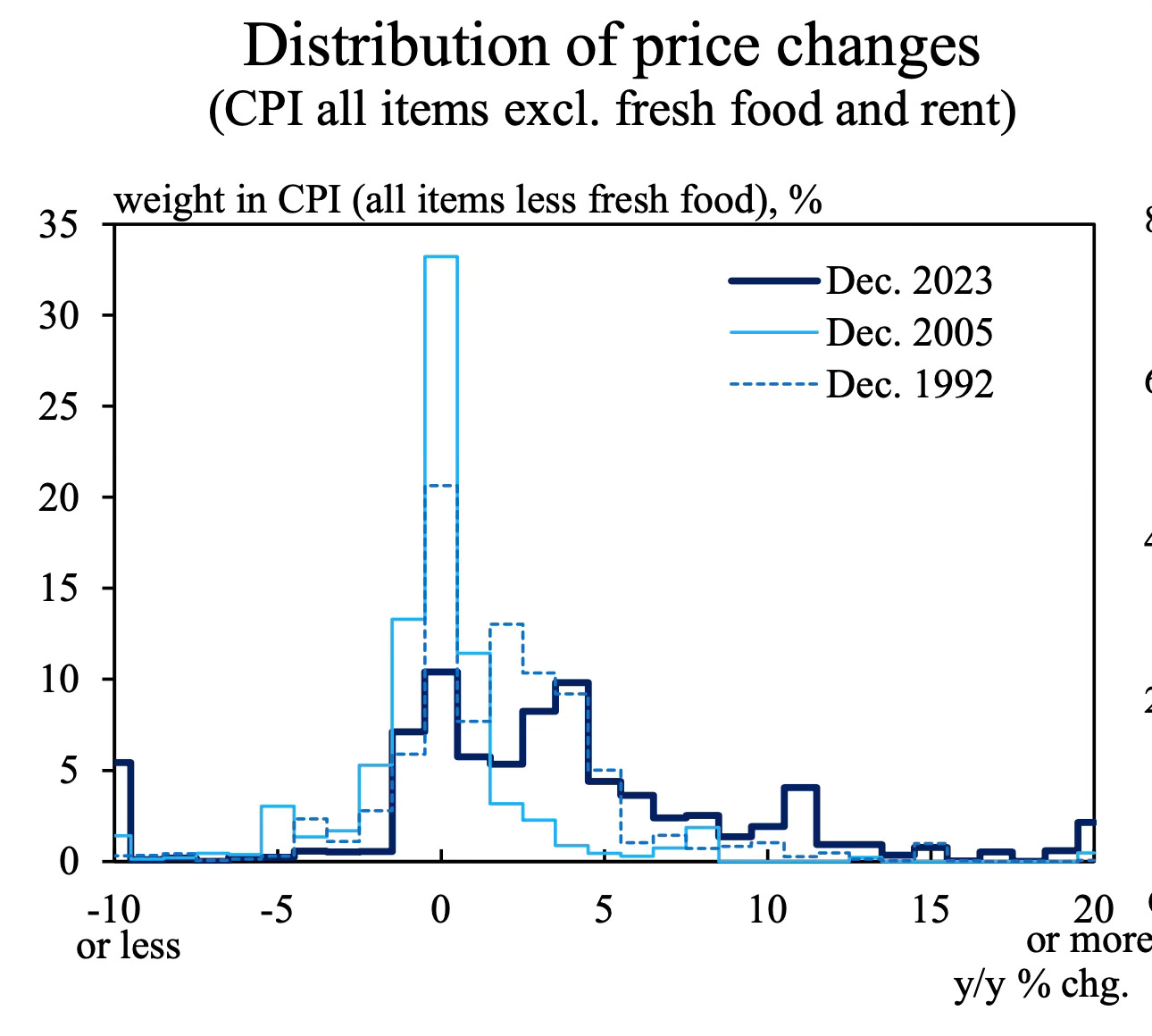

As I learned at the conference (Kakuho, Hogen, Otaka, and Sudo 2024), Japan developed a “no price change norm,” in which most businesses do not change prices and customers expect no price changes. Most of the conference discussion thought this a terrible thing, and celebrated the return of inflation to break that norm.

This too may be regretted. We all wish expectations to be “anchored.” Zero is a much clearer anchor than 2%. If I say “inflation is 2%, I’m raising prices 2%,” my customers will react, “well, your supplier’s inflation, your city’s inflation, your wage inflation is less than 2%, inflation is mismeasured, what about core/supercore/ex housing, etc.; you’re trying to take my money.” Zero is zero.

The expectation of no price level change is much stronger than an expectation that inflation will somehow get back to 2% by central bank resoluteness, It applies to individual goods, not just the average.

So, a steady price level and a widespread zero price change norm for individual goods is much stronger anchoring than an inflation target. If Japan manages to join the rest of the world at a hoped-for 2%, the BoJ may well regret finally getting what it wants rather than what it needs!

[at the substack limit. Go to the next post for part 2, Inflation and Fiscal Theory]

This story is not original. I heard it in casual conversation, but I don’t remember who I was talking to or what paper they were citing. If anyone knows the correct citation, please write.

First, I am not an economist, but I do very much enjoy the work of such an economist as this paper provides. The various actions and results provide insight and understanding of what is happening at levels far exceeding other types of study, save perhaps factual history.

However neither can provide the future.

My thanks to John Cochrane for showing the history along with the economic facts and theories of what happened and what might happen.

I look forward to the future.

GDP per working age person!

This is the most important metric that should be most often quoted, and measured, and most discussed by most economists.

Fertility is an important aspect of it, so the worker/dependent ratio is also an important metric, so far not mentioned here.

“Microeconomic inefficiency” seems an excellent term to describe the important differences for actually having businesses adapt to changes.

More parts coming, oh my! The huge Japanese debt discussion likely coming.