Inflation, Monetary and Fiscal Policy, and Japan. Part 4: Decisive Experiments

(This is part 4 of a longer essay. The whole thing pdf here if you prefer.)

4. Japan provided crucial experiments

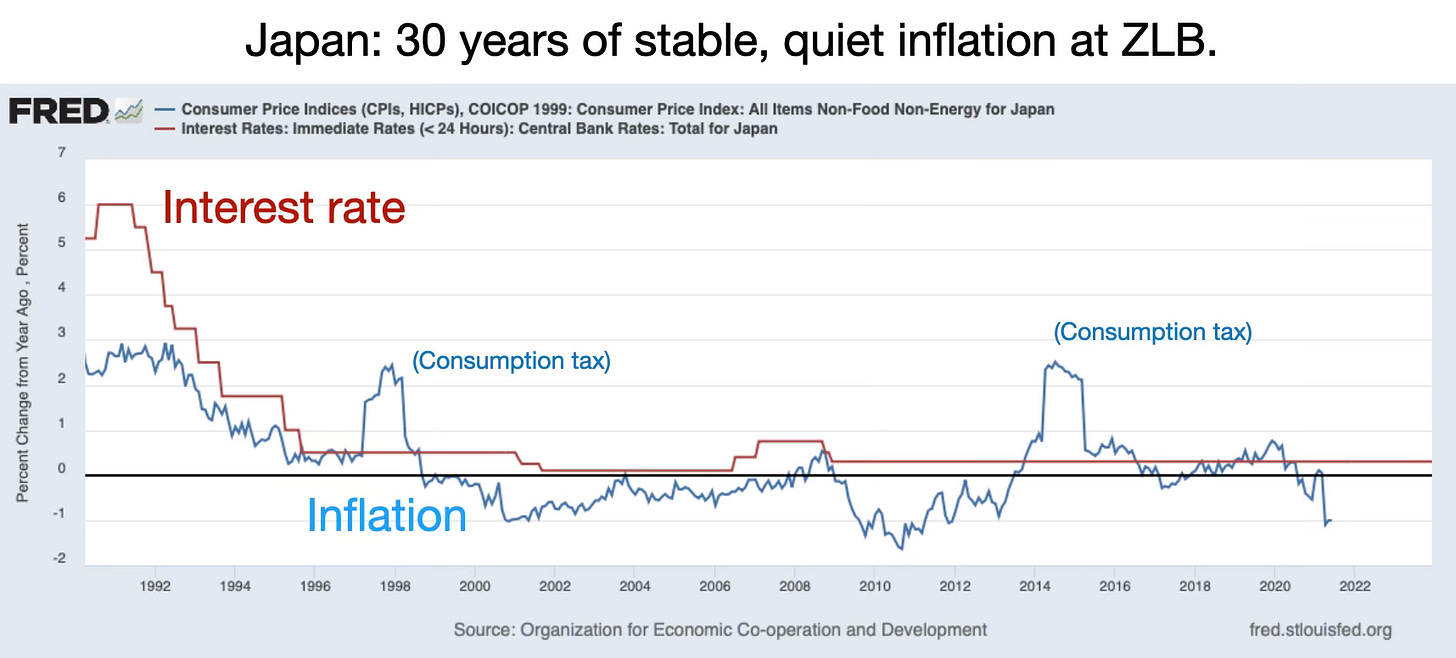

Japan’s 30 years at the zero bound, with huge QE, also provided the world with a crucial experiment that decisively lets us distinguish theories of inflation.

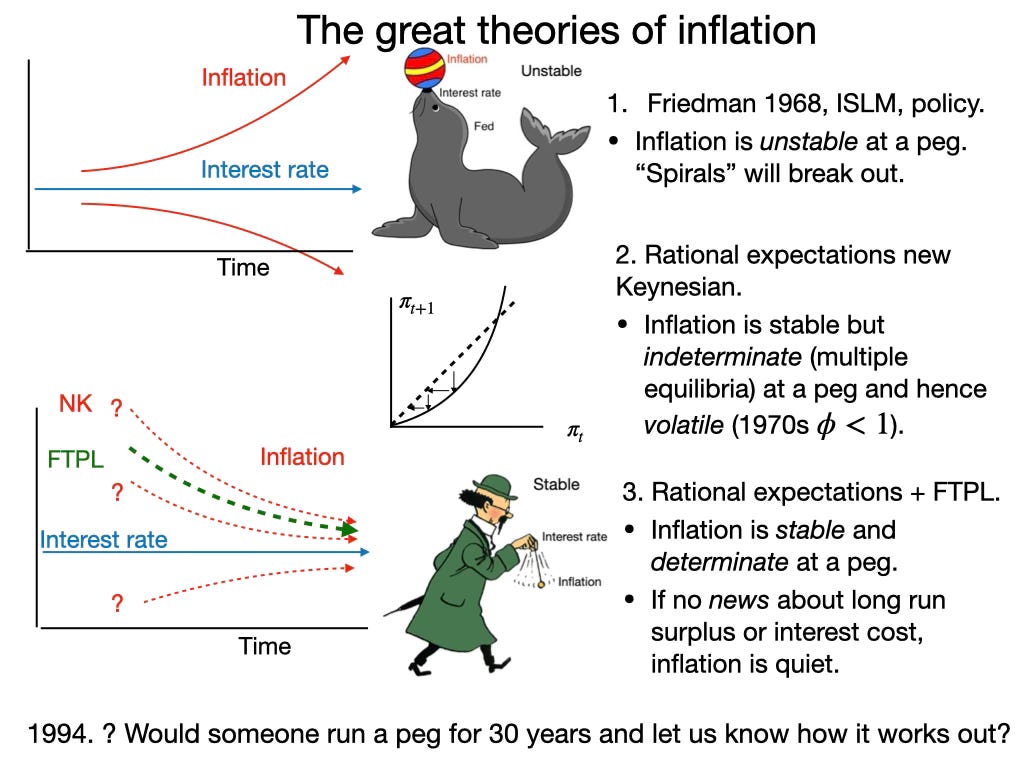

The most classic theory of inflation under an interest rate target, unifying Milton Friedman (1968), ISLM adaptive or “anchored” expectations models, and the verbal doctrines espoused uniformly by central banks, policy institutions and commentators (though unpublishable in any contemporary academic journal) states that inflation is unstable under an interest rate peg. The central bank must swiftly move interest rates in response to inflation, like a seal balancing a ball on its nose, to keep inflation from spiraling away. If the bank fails to do that, as alleged of the 1970s, or if the bank is constrained from such movement, as occurs at the zero bound, an inflation or deflation “spiral” will develop. At the zero bound, a small deflation means a high real interest rate, that lowers aggregate demand, lowers output, creates more deflation, and around we go without limit.

When Japan hit the zero bound in 1994, and when the US and Europe did so in 2008, the central bank and policy community widely and correctly, given the logic of this theory of inflation, warned of a spiral to come and urged heroic efforts to avoid it.

New-Keynesian theory developed since the early 1990s uses rational expectations. These models are universal in the equations of central bank and academic research, though not always in the words describing those equations. These models use rational expectations. They predict that inflation is stable at a peg or zero bound, but indeterminate. There can be multiple equilibria, and excess volatility as the economy bats uncontrollably between multiple equilibria. This is not a small technical issue. Given that inflation is stable, multiple equilibrium volatility is the central new-Keynesian complaint of 1970s monetary policy. In this theory, the Taylor rule worked in the 1980s by eliminating multiple equilibria (Clarida, Gali and Gertler 1999, 2000). New Keynesians warned loudly, and correctly given the model, that any return to the zero bound would lead to more such volatility (Benhabib Schmitt-Grohé and Uribe 2001, 2002).

Adding fiscal theory to new-Keynesian rational expectations models, we at last obtain a theory of inflation under interest rate targets that is consistent with current institutions (interest rate targets rather than money supply control, central banks do not make explosive off-equilibrium threats). It says inflation is both stable and determinate under an interest rate peg. Inflation surprises come from fiscal surprises, so inflation will also be quiet (the opposite of volatile) if there is no bad fiscal news — if people expect deficits to be repaid eventually.

This stability and quiet works much like an exchange rate peg. We all understand how an exchange rate peg can nail down the exchange rate and relative price levels, if a government is fully committed to the peg and always provides the necessary fiscal resources to back the peg. Pegs unravel when they do not have that fiscal backing. The proposition of stability at an interest rate peg requires the same backing. Most observed interest rate pegs until 1994, and especially those referenced by Friedman (1968), did not have that backing. Indeed, governments imposed interest rate pegs as a suite of financial-repression measures intended to lower interest costs of a stressful fiscal situation.

Until 1994, we genuinely did not know the answer to this central question. What happens at an interest rate peg or zero bound, not undertaken to paper over fiscal problems or in the depths of a Great Depression? Given existing economic theory and experience, worries were justified.

Japan ran the experiment. It stayed at the zero bound for 30 years. Inflation just batted within a percent or two of the zero bound, perhaps the quietest price level the world has ever seen. No spirals, no multiple equilibria. Those theories are simply wrong.

Fiscal theory adds insight. A “deflation spiral” raises the payoffs to bondholders, or equivalently lowers nominal tax revenues but not nominal payments due to bondholders. The government must respond to deflation with fiscal austerity, higher taxes and lower spending, to pay this windfall to bondholders. In deflation spiral models, the government does so, though usually only in the footnotes that mumble something about lump-sum taxes. But nobody expects our governments to respond to deflation with austerity. Governments respond with stimulus, and helicopter money, with a string of negative primary surpluses. Given that expectation, deflation can’t happen.

This experiment is crucial for the great question of monetary policy: Why do central banks have a 2% inflation target, not zero, and not a price level target? The main reason, as of 1992, was fear of a tipping point, that the zero bound represented a dangerous entry to a “deflation spiral,” a repeat of the great depression “liquidity trap” and so forth. Japan’s experience proves that this fear, valid as of 1992, is unfounded. Zero inflation is possible and does not lead to deflation spirals. Fear not.

(The second reason is the idea that 2% inflation allows greater stimulus by lowering nominal rates in recessions, a version of the theory that wearing too-small shoes during the day makes it feel so good to take them off at night. I also disagree with this analysis, but that’s beside the point today of what we can learn from Japan.)

Now, the asterisk is crucial. A peg or zero bound is stable and quiet if there is no bad fiscal news, if people think deficits will be repaid. The proposition is only that a peg or zero bound can be stable and quiet, if these fiscal preconditions hold.

Japan is also the classic case of ineffective fiscal stimulus.—Even immense fiscal stimulus does not cause a boom in aggregate demand (I would add, with Ricardian expectations, that the new debt would be repaid). Large amounts of infrastructure spending did not lead to strong growth — and a huge debt to GDP.

Doesn’t the large expansion stretch the fiscal preconditions? Yes, but stretch, not violate. Remember, what matters in fiscal theory is debt relative to expected repayment, and low interest costs count in that expectation as well.

Many of my compatriots who flew here with a deflation spiral mindset, and advocating even more fiscal stimulus, impolitely pointed out that Japan never fully committed to the idea that it would not repay debt, a commitment needed to create stimulus and inflation. To create inflation you must threaten unsustainable debt. As soon as sustainability looked to be an issue, there goes Japan raising consumption and other taxes again! It is very hard to shake a reputation for long-term sober fiscal policy, especially if you don’t really want to do it. That criticism, together with a global era of very low real interest rates, explains why these big deficits did not cause inflation.

I take a different lesson: Japan’s 30 years of massive deficits, combined with a thrifty reputation for responsible repayment, show that Ricardian equivalence really does hold, that flow deficits have no effect if people expect repayment, that Keynesian fiscal stimulus is pointless.

I emphasize: fiscal theory says you get inflation if debt exceeds faith in a country’s long run ability and will to repay. There is no hard and fast debt/GDP limit. Argentina has debt crises at 40% debt to GDP. Japan lasted a decade at over 200%.

Monetarism

Japan also offers us an immense and decisive experiment to distinguish fiscal theory from the most classic theory of inflation, monetarism. One can also object in theory, that monetarism requires central banks to control the money supply. If they target interest rates, monetarism predicts an unstable price level. But we have an even simpler and dramatic test before us.

Monetarism and fiscal theory agree that if the government drops $5 trillion of cash on people, and they have no expectation of future taxes to soak up this money, you get inflation. That’s a rise in the money supply but also a fiscal transfer, an unfunded deficit. The question is, what happens if the government gives people $5 trillion of cash, but takes away $5 trillion of treasury debt? Monetarism says that this gives the exact same inflation in both cases, as only the money supply matters. Fiscal theory says, to first order, there is no effect on inflation. (I hedge with “to first order” as if money pays less interest than bonds there is a small seignorage effect, and QE also shortens the maturity structure of debt.)

Would someone please run the experiment? The US just did: First, about $4 trillion in QE which had no effect at all on inflation, and then $5 trillion covid spending, about $3 trillion of which monetized, which promptly produced about 15% cumulative inflation.

This is notable, because of the immense size of the experiment. Reserves used to be $10-$50 billion. $4 trillion is a bomb, not a firecracker. It should have set off Zimbabwean levels of inflation, and here we are arguing about 10 basis points of announcement effects in long term bond prices.

Was that not enough? Japan offers an even larger experiment. The BOJ’s monetization is close to 100% of GDP, where even the Fed can only get to about 25%.

These are as decisive experiments as we get in economics. We often fret about subtle econometric tests, with little correlations and argue whether t or F statistics on an impulse response function are significant. We argue about identifying assumptions and model specifications. Stability, determinacy, and the effect of QE vs covid spending are massive simple tests of the basic robust doctrines of each theory, not remediable by small changes. Thank you Japan!

(Later in the conference the question whether QE is effective or not came up. We study small time series announcement effects in the US and EU. But let us look across countries. Japan did 4-5 times as much QE as the US and EU. And got less inflation out of it. Unless you argue that Japan faced exactly 4-5 times as large “headwinds,” and 4-5 times less costs stopping all countries from doing more powerful QE, that’s pretty strong evidence that QE doesn’t do much to raise inflation.)

The combination of a zero bound, complete satiation in liquidity via an immense balance sheet, and a completely stable inflation for 30 years unseat the central tenets of standard doctrine spanning Friedman and ISLM policy analysis. It is possible to live the Friedman optimal quantity of money. Pretty much nobody thought this was true before Japan did it. Per ISLM analysis, Inflation or deflation spirals would break out. Per monetarism, the immense quantity of money would cause hyperinflation. Though Friedman described the “optimal quantity of money” as a zero interest rate and satiation in money, he never advocated a peg at zero, preferring instead a k% money growth rule with low and positive inflation.

(Keep going to the next post for part 5, sustainability.)

"The question is, what happens if the government gives people $5 trillion of cash, but takes away $5 trillion of treasury debt? Monetarism says that this gives the exact same inflation in both cases, as only the money supply matters."

Maybe under straw man monetarism...

Treasury debt can offer liquidity services and serve as a partial substitute for money. If you're measuring money supply with a simple sum statistic, then it's not going to capture this effect. That's why things like Divisia monetary aggregates were created. During the GFC, Divisia M4 including Treasuries didn't see anywhere near the same movement as M2.

Loans = deposits, not the other way around. So, the multiplication process produces breathtaking relationships. For example, the source of interest-bearing deposits is non-interest-bearing deposits either indirectly through the currency route or through the bank's undivided profits accounts.