Inflation, Monetary and Fiscal Policy, and Japan. Part 5, Sustainability

(This is part 5 of a longer essay. The whole thing pdf here if you prefer.)

5. Fiscal Limits on Monetary Policy, Debt Sustainability and Future Inflation

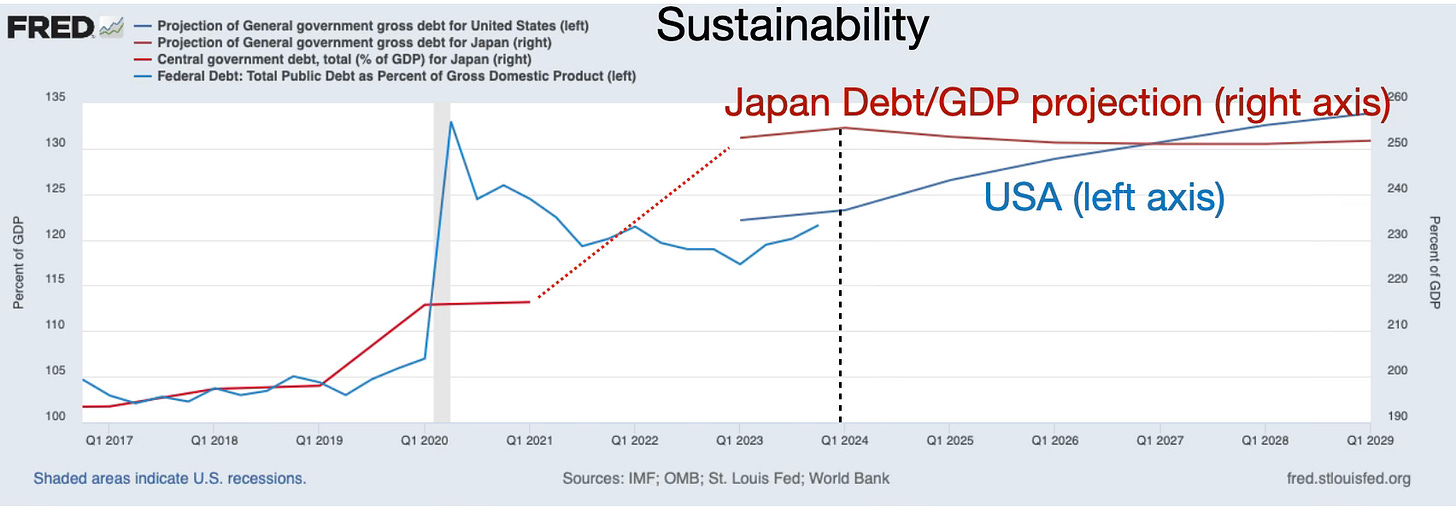

Large debts, and poor plans for repaying them, also are a constraint on monetary policy. In the last great disinflation in the US, 1980, the debt/GDP ratio was 25%. It is now 100%. All of these influences are four times larger — and the fiscal limits on monetary policy were already evident in that episode.

This is a first-order effect. In the US, with 100% debt to GDP, each 1 percentage point rise in the real rate is 1 percentage point rise in interest costs, which raises the deficit 1 percent of GDP. That’s a lot. In Japan, with 250% debt to GDP, the same 1 percentage point rise in interest rate costs 2.5% of GDP more deficit!

Higher interest rates have knock-on fiscal effects. US bank regulators let banks load up on long-term bonds while the Fed was preparing to raise rates. When rates go up, banks go down. Monetary authorities may fear raising rates as a result. This “financial dominance” is also basically a fiscal effect, since bank failures will occasion fiscal bailouts, which have to come from the same empty pot.

Higher interest rates cause recessions, which cause more stimulus, bailouts, and social programs. This is not an unintended consequence. In standard macro, it is the essential mechanism by which higher rates cool inflation; it is a feature not a bug. Higher rates lower demand, that lowers output, and via the Phillips curve that lowers inflation, all with “long and variable lags.” But it also is another fiscal impact of monetary policy.

In contemporary macroeconomic (not fiscal theory!) models, fiscal policy automatically tightens to pay these costs. If fiscal policy does not or cannot tighten, interest rates lose their power to lower inflation. If another bout of inflation comes, as the last one did, from fiscal policy, higher interest rates will just be gas on the fiscal fire. Central banks in fiscally constrained economies may turn out to be a lot less powerful than we think.

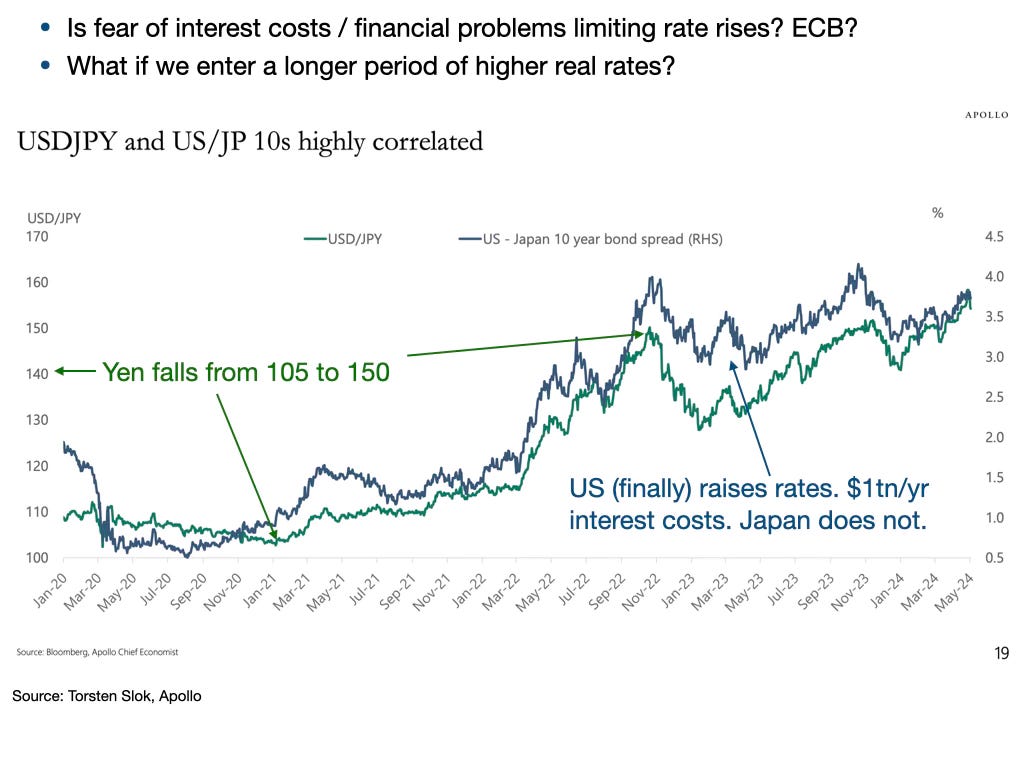

These limitations may already be playing out. The Bank of Japan has not raised interest rates anything like as much as the US Fed has done. The yen has lost a third of its value. Is the BoJ nervous about the fiscal and financial consequences of raising interest rates? The ECB owns a lot of Italian (160% debt to GDP) and other sovereign debts. If it raises interest rates, those countries may again be in trouble. The ECB is now directly involved as it owns so much sovereign debt, and is committed to buying more to keep sovereign spreads low. If inflation rises again, will it be able to raise rates, and will doing so lower inflation? The US Fed must certainly be aware of the $1 trillion in interest costs that the Treasury is now paying, and its own large mark-to-market losses which mean less money flowing back to the Treasury, to say nothing of the large number of banks in a similar position without the ability to print money.

Sustainability

Of course, I cannot close without some mention of the debt “sustainability” question.

I start with the situation in the US. The CBO projection, of ever rising debt to GDP and perpetual large primary deficits is not sustainable. This won’t happen. We know that. We only don’t know how the world will be different: more tax revenue, less spending, inflation, default, growth?

The CBO projections are optimistic. They are not forecasts, conditional expectations. They enshrine parts of current law that everybody knows will change. More importantly, they assume that nothing bad ever happens again. Notice the past debt ramped up in big waves during 2008 and 2020. The future will look more like my line, ramping up again in the next crisis and the one after that. Except it wont, because that is even more unsustainable.

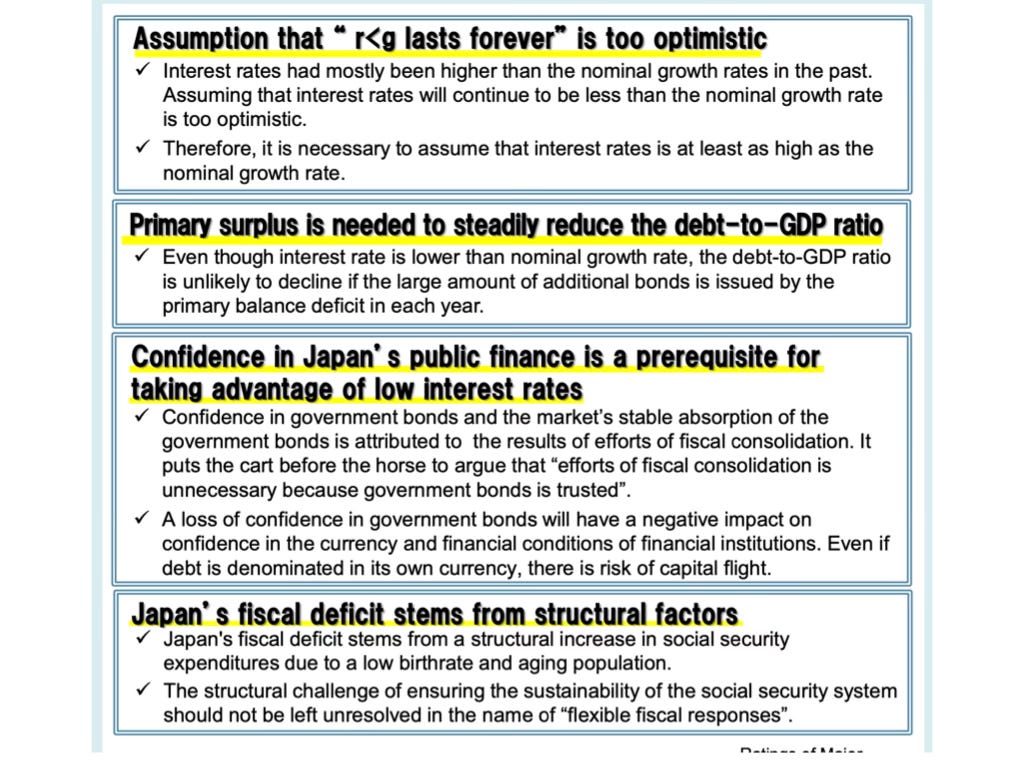

The US and Japan do not have debt problems, they have spending problems. Japan, and the Victorian UK before her, showed that 150% or 200% debt to GDP is possible, if people have confidence in a sober fiscal policy with steady small surpluses that can repay it. The US problem is spending in excess of tax revenue. Even if we defaulted on or inflated away all our debt today, we would still have a yawning fiscal gap — and a worse problem, because nobody would lend the US any money at all. Raising tax rates to European levels will give the US European growth. I see spending reform — we waste gargantuan amounts of money—tax reform — more revenue at lower rates — and above all pro-growth microeconomic policy as the only solution.

Our bond yields are still low. Clearly markets have faith that the US will in the end take these simple steps to fiscal sobriety after we have tried everything else.

In the meantime, I see the big imminent danger not in these projections, but in the potential loss of fiscal space to borrow in the next crisis. If China invades Taiwan, another pandemic breaks out, or some other crisis happens, the US will want to borrow and print a tremendous amount of money. With no plan to pay it back, markets may refuse, producing inflation much more quickly this time than last time, and limiting the US ability to marshal resources necessary to fight the crisis. Debt crises always need a spark. Debt is just the gas on the floor. Debt and so far unreformed long-run spending plans make the system fragile.

Every time I give a fiscal theory talk, someone says “well, what about Japan?” Let me briefly suggest some standard answers, though I hope to learn much more at this conference.

That Japan has a large debt to GDP and so far little inflation is not a “test” of the fiscal theory of the price level relative to other theories. That the US has a large debt to GDP and poor deficit projections, only a little inflation so far, and moderate long-term bond prices, is not a “test” of the fiscal theory of the price level. If only economic theories could be so swiftly defeated by armchair analysis.

First, who is to say that people do not expect Japanese debt to be repaid, or for my own great country to enact simple and sensible reforms before the CBO’s projections bear out and a debt crisis hits? Again, debt sustainability depends on debt relative to expected future ability and will to repay, which includes interest costs. None of our indebted countries are past the ability to repay. Indeed, the squishiness of expected future surpluses, like that of expected future dividends, actually makes it very hard to find testable implications of present value analysis — which makes it very hard to find armchair rejections.

Second, debt sustainability is a necessary feature of all macroeconomic models. Old Keynesian, new Keynesian and monetarist models all include the same condition that the value of government debt equals the present value of surpluses. They just imagine different mechanisms for this equation to hold. If it does not hold, if we could say with certainty that the present value of surpluses is not equal to the value of debt, then all the other theories are in just as much trouble as fiscal theory. Unsustainability is not a test of fiscal theory in favor of monetarist, old or new Keynesian theory.

Third, there is much new work involving r<g, liquidity values of government debt, overlapping generations and other frictions that makes present values technically hard. I won’t address this today, other than to say that most of this doesn’t undermine fiscal theory, and much of what seems to is wrong. A simple example: Suppose a government finances itself only with non-interest-bearing money. Well, the rate of return on government debt, negative of the inflation rate, is less than the growth rate. If you try to discount surpluses with that, they seem to blow up. Yet we all know government debt is not a free lunch; if that government prints more money to finance deficits, it gets more inflation. Liquidity values of government debt can lead one astray in the same way.

So how has Japan gotten away with such huge debt to GDP for so long? How about the US? Bondholders, somehow think they will be repaid, but bond markets never see crises coming. If they did, the crisis just happened.

A few answers, and a few ways that Japan might actually be safer than the US, pop up. First, consider debt:

Japan’s debt is overwhelmingly held by domestic (85%) investors. These are also more passive than foreign financial institutions and central banks who hold much US debt, and might dump it. The ultimate holders are elderly Japanese people, notoriously more thrifty than Americans, who would have sold this debt and gone on a round-the-world cruise long ago.

Japan has an estate tax, which kicks in at 10,000,000 yen, about $66,000. Some of that debt is coming back.

The Japanese government and central bank have a lot of assets, so the actual net debt is only about 160% of GDP. Still “only” as large as Italy is not much comfort. Japan as a country has run decades of trade surpluses, accumulating foreign assets. The US has done the opposite.

Japan’s debt has a longer maturity than the US. That means it takes more time for higher interest costs to hit the budget, and makes Japan less prone to roll over problems. Both our central banks have rather dramatically shortened this maturity, however, and higher interest costs are starting to biter.

Low interest costs. We economists love present values, but politicians and to some extent markets think in terms of costs. If the monthly payments are low, they carry on. I think in fact this accounts for the large increase in debt. If markets are charging plus or, better, minus one percent, why not borrow a huge quantity? Low interest costs have made debt sustainable. Of course whether they will continue to do so is the big question. Higher interest costs can make debt quickly unsustainable. (See also Chien, Cole, and Lustig 2024.)

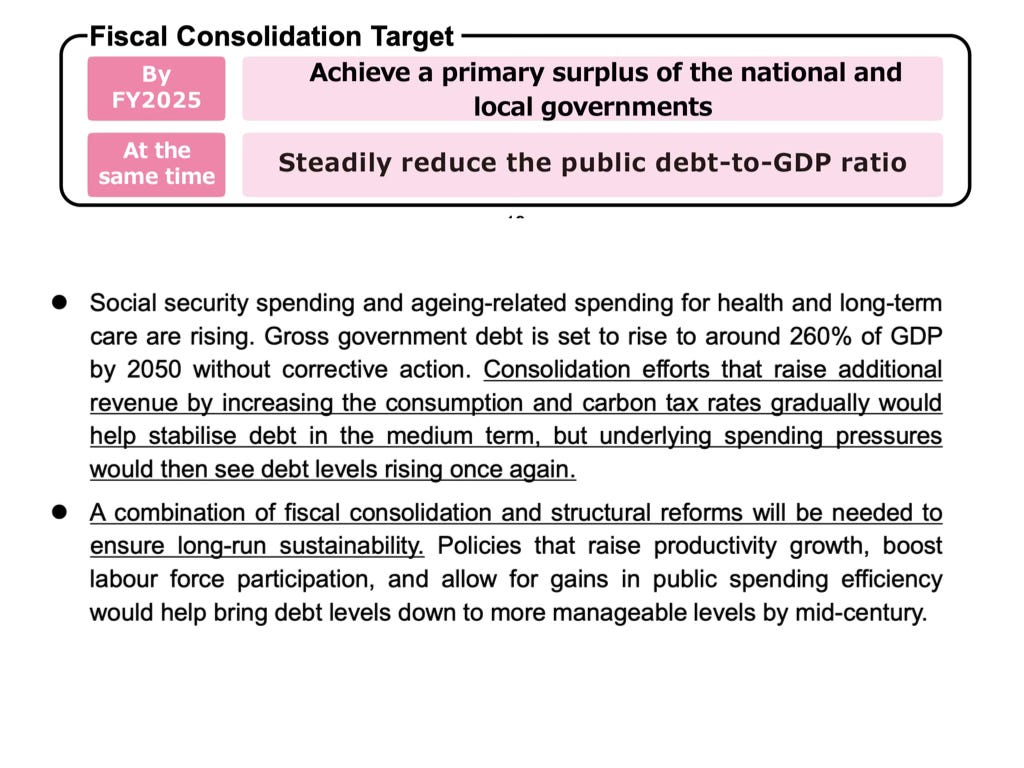

The underlying problem is, again, not debt, but the yawning projections of future deficits. Those come primarily from a rapidly aging population, sharply declining birthrates, making pay-as-you-go pension and healthcare promises unsustainable. Which country is in more trouble?

The US has an alternative source of people — immigration, if the US will only reform its chaotic immigration system to allow in “economic migrants,” young people who want to come, work, and pay taxes.

Japan has recently increased its consumption tax. Every time I mention “consumption tax” in the US, an outcry follows — old people paid income and social insurance taxes when young, how dare you tax them again when they want to spend the money when they are old. Japan did this seamlessly!

More generally, the US social insurance programs were pitched as and promised to be a “savings” program. You get out what you put in. They are slowly becoming pure transfer programs, but that transition is politically extremely painful. For example, eliminating the income cap on social security contributions in the US would admit it is no longer a savings program, and just a transfer from rich to less rich. That is not entirely an easy switch, as doing so also multiplies the disincentives of the programs. But it is the natural direction that closing the gap may go. My understanding is that Japan’s programs were always transfer programs, so Japan does not face that limitation.

This seems to me an argument for the most important underlying question, which society will have the social and political cohesion to undertake the simple reforms that are needed to put our tax system and social programs on a sustainable basis?

I venture there is a greater faith in the general function and long run responsibility of fiscal policy in Japan than the US, a greater reverence for repaying debt. Do not count on the US not to default, when it comes down to checks for voters vs. principal and interest to Wall Street and foreign central bankers.

Perhaps I’m just a starry-eyed foreigner and too aware of US political dysfunction, but I’ll chalk that one up to Japan.

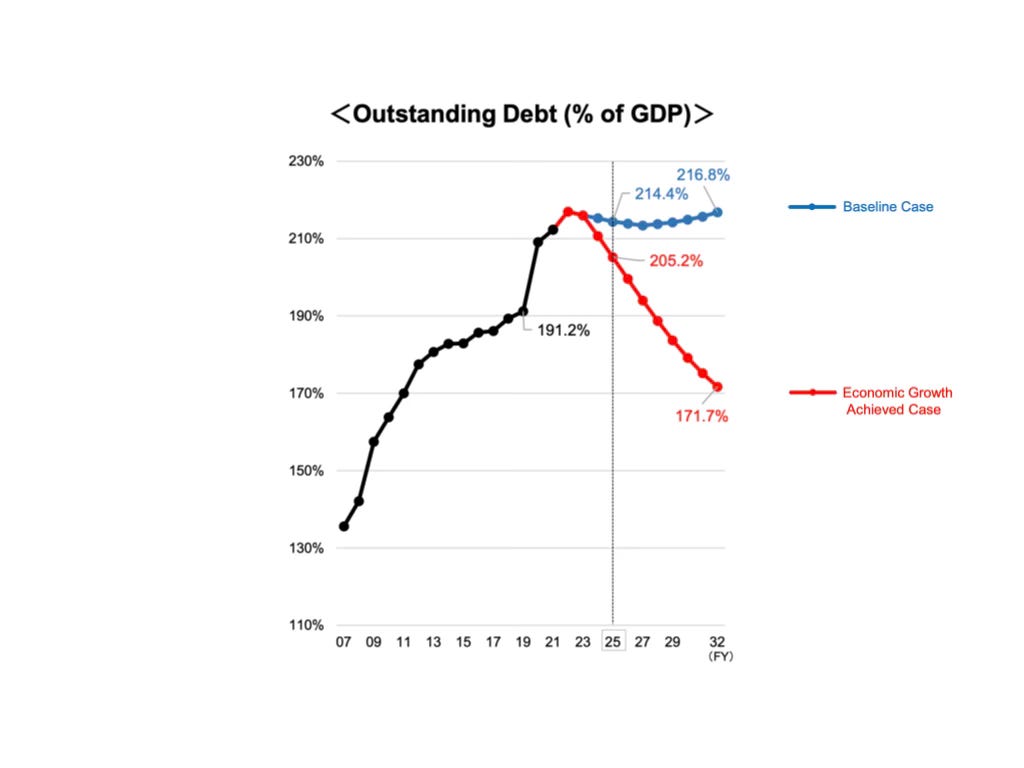

As some evidence, I plot the best projections for Japanese debt that I could easily find, and contrast with the US CBO projections above. Apparently Japan has converging fiscal projections.

As more evidence, here are some with some pictures from the Japanese Public Finance Fact Sheet, Ministry of Finance. The MoF says essentially the same things I have said. I got hopeful by this report, but conference participants inform me that the MoF has been sounding this alarm for years with little effect. The CBO has been sounding similar alarms in the US, but the Treasury department has not, so I still find hope that an important voice in Japanese official policy understands the issues so clearly.

(Growth is the answer!)

Solving the long run fiscal problem.

Solving the long run fiscal gap faces some straightforward tradeoffs.

One may say “just raise taxes,” but tax rates are already high. If a government spends 40% of GDP, the average tax rate is 40%, and for everyone who pays less someone pays more. Distortions are proportional to the square of the tax rate. It is common to say we are on the left hand side of the Laffer curve, but that calculation usually considers only static labor/leisure tradeoffs. The consideration for our fiscal situation is 20 to 50 years or more of growth, and incentives to save, invest, innovate, get education and training, and so forth. Long run growth may be more affected by tax rates than a one-year labor/leisure tradeoff suggests.

Some social program cost cutting measures, such as raising the retirement age to match an older and healthier population, are economically straightforward, but politically difficult. A better way out involves social program reform — improving the large disincentives that pervade US social programs. That can help more people at lower cost. I don’t know anything about disincentives in Japanese social programs to say if this will help.

Some people will get less. I think it’s possible to give less to people who don’t really “need” it, recognizing that all transfers embody value judgments beyond the expertise of economists. I think it’s possible to improve incentives so that more people don’t “need” social program help. Remember, almost all the money goes to “middle class,” not “poor” people.

But in the end, our governments made a deal with the retiring generation: We will put in pay as you go old-age assistance. You have babies so there are workers to pay for your retirement. We embarked on a social version of the ancient practice of relying on children for one’s old age, rather than the apparently more modern practice of investing in physical capital to support one’s old age. But we forgot that the individual incentive to have children in that system is eliminated when we rely on our collective children to support us in old age. Why raise children to support someone else’s old age? The generation of current workers, naturally, didn’t keep their end of the bargain. Our societies will simply not be able to provide as many pays-as-you-go transfer benefits as we thought.

In sum, tax reform — lower marginal rates, larger base, such as a consumption tax — social program reform — fewer disincentives to work and over-use health care — and overall microeconomic reform to raise long-run GDP growth are the straightforward answer to the fiscal problem.

Moreover we live in a time of great promise. AI and biotech offer a chance at a new wave of growth. But we also live in a time of great peril. Industrial policy, the new nationalist mercantilism, tariffs and subsidy wars, can explode budgets and cut off growth.

Our spending problems are internal, not external. Letting this fester to cause a debt crisis would be a massive self-inflicted disaster. Let us hope our societies live through the fragile period and do not fall apart in this preventible way.

References

Balke, Nathan S. and Carlos E. Zarazaga, 2024. “Quantifying Fiscal Policy’s Role in U.S. Inflation” Manuscript, https://bpb-us-w2.wpmucdn.com/people.smu.edu/dist/a/1609/files/2024/04/Quantifying_Fiscal_Contribution_to_US_Inflation_3_2024-81aa51c1758669d0.pdf

Chien, LiLi, Harold L. Cole, and Hanno N. Lustig, 2024, “What about Japan?” Stanford University Graduate School of Business Research Paper No. 4620159 https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4620159; https://www.nber.org/papers/w31850

Cochrane, John H. 2023. The Fiscal Theory of the Price Level. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Cochrane, John H. 2024a. “Fiscal Narratives for US Inflation.” Manuscript. https://www.johnhcochrane.com/research-all/sims-comment

Cochrane, John H. 2024b. “Expectations and the Neutrality of Interest Rates.” Review of Economic Dynamics 53, 194-223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.red.2024.04.004

Fernández-Villaverde, Jesús, Gustavo Ventura, and Wen Yao, 2024. “The Wealth of Working Nations.” Manuscript, https://www.sas.upenn.edu/~jesusfv/Wealth_Working_Nations.pdf

Furukawa Kakuho, Yoshihiko Hogen, Kazuki Otaka and Nao Sudo 2024. “On the Zero-Inflation Norm of Japanese Firms.” Manuscript.

Shirakawa, Masaaki 2023. “Time for Change.” Finance and Development, International Monetary Fund. (March) https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/fandd/issues/2023/03/POV-time-for-change-masaaki-shirakawa

Smets, Frank and Raf Wouters, 2024. “Fiscal backing inflation and US business cycles” Manuscript https://www.hoover.org/sites/default/files/2024-04/- SW24.pdf

Uchida, Shinichi, 2024. “Price Dynamics in Japan over the Past 25 Years.” Manuscript.

Whether Economists suffer from physics envy, real science and history will judge. But whether a country with excessive debt/GDP AND short duration debt (US) can inflate away its debt before markets awake and raise Real rates is the real question.

Well, I really enjoyed this five-part series, and I appreciate John Cochrane presenting this to the public. The internet has ruined everything, but in the meantime it has elevated discourse on certain rare issues for the lay public.

I am on board with smaller government! If I was any worse, I would be the type of right-winger with a permanent scowl on his face.

But I ask this every once in a while, and earnestly: Does not the large BoJ holding of JGBs increase the likelihood that the national government can pay down the debt, or at least honor debt payments? After all, the interest flows into the central bank, and then back to the national government.

Should the Federal Reserve start building its hoard of USTs, for the same reason?

(Yes I know, once the two major parties figure out the central bank "can monetize debt"....)

A side observation: Last time I did a back-of-the-envelope look-see, the globe had about $450 trillion in assets, bonds, equities, property. Money is fungible, flows easily between assets classes and nations.

OK, so enormous pools of global capital, and growing every year. Some say there are "global capital gluts" due to high savings rates in much of the world, and world is getting richer every year. Even more savings as people move out of dire poverty.

OK, let's say the Fed adds a few trillion more to its hoard of USTs in the next few years. What will happen to global interest rates, as a result? Remember, rates on USTs are set globally, not domestically. Huge, huge financial markets of which the USTs are only a small part.

My guess is hardly anything would hapen to rates o USTs, if the Fed added a few trillion to its balance sheet.

https://fraser.stlouisfed.org/title/economic-letter-6362/inflation-always-everywhere-a-monetary-phenomenon-607694

These guys from Fed Dallas (see above) talk up the national government buying property mortgages, and stabilizing currency. But I think the same thing holds for USTs.

Maybe a realistic path forward: The Fed builds its balance sheet somewhat. The US tries to cut red ink. Allow some inflation, 3% is not so bad.

And then pray that AI rescues us all.