Inflation, Monetary and Fiscal Policy, and Japan, Part 3. Post-covid inflation

(This is part 3 of a longer essay. The whole thing pdf here if you prefer.)

Supply shocks?

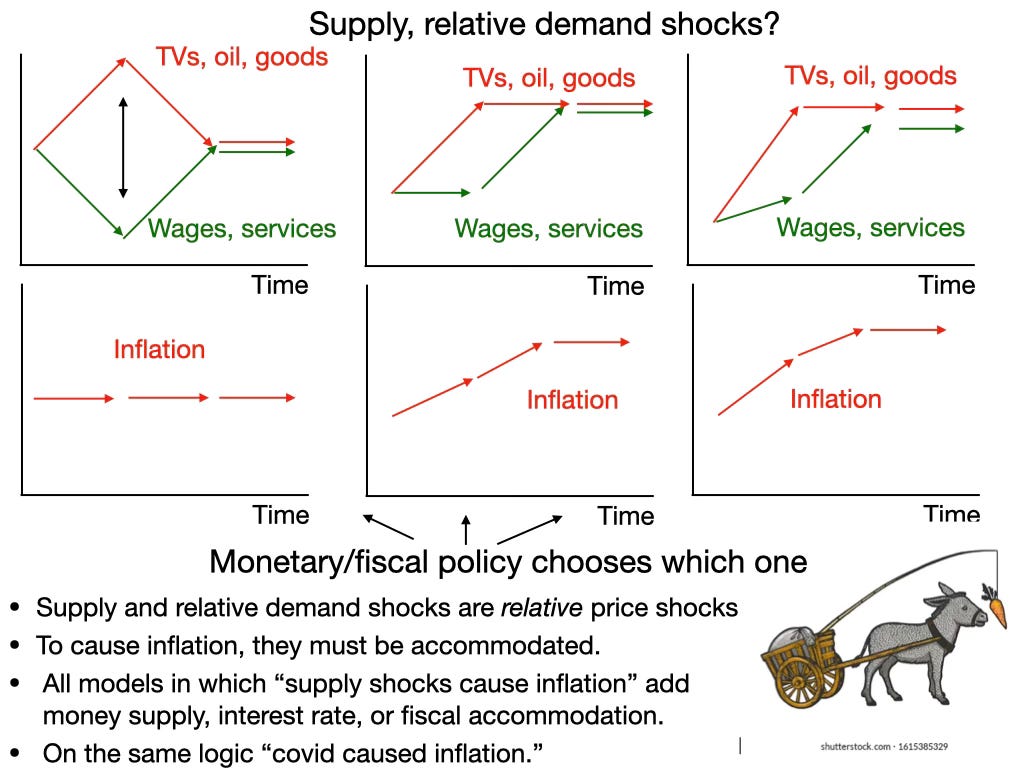

I leave out here “supply shocks,” and the less serious greed, price-gouging, monopoly, and shrikflation excuses for inflation, as I do not see that we need them. Supply shocks in particular are fundamentally shocks to relative prices, not to the price level. To generate inflation rather than a transitory spike in relative prices, monetary or fiscal policy must accommodate supply shocks with more demand. New-Keynesian models with supply shocks do that with both larger money supply and larger “passive” fiscal policy changes. (This is true, for example, of Balke and Zarazaga 2024 and Smets and Wouters 2024, who estimate new-Keynesian models with fiscal theory and estimate substantial “supply shock” effects on inflation.) Then the supply shock really is just the occasion for a monetary-fiscal expansion, the carrot in front of the monetary-fiscal horse that pulls the inflation cart. The same supply shock with no accommodation has no inflationary effect. Why then call it a “supply shock” rather than a “supply induced demand shock,” which it is? We might as well call it a “covid shock,” as the original shock was the pandemic, not to supplies. OK, covid led to behavior and policies that shut down the economy, the government responded with huge fiscal stimulus, and we got inflation. Is that a “covid shock” that causes inflation? No. Covid induces fiscal and monetary policies that cause inflation.

3. Japan vs. US inflation

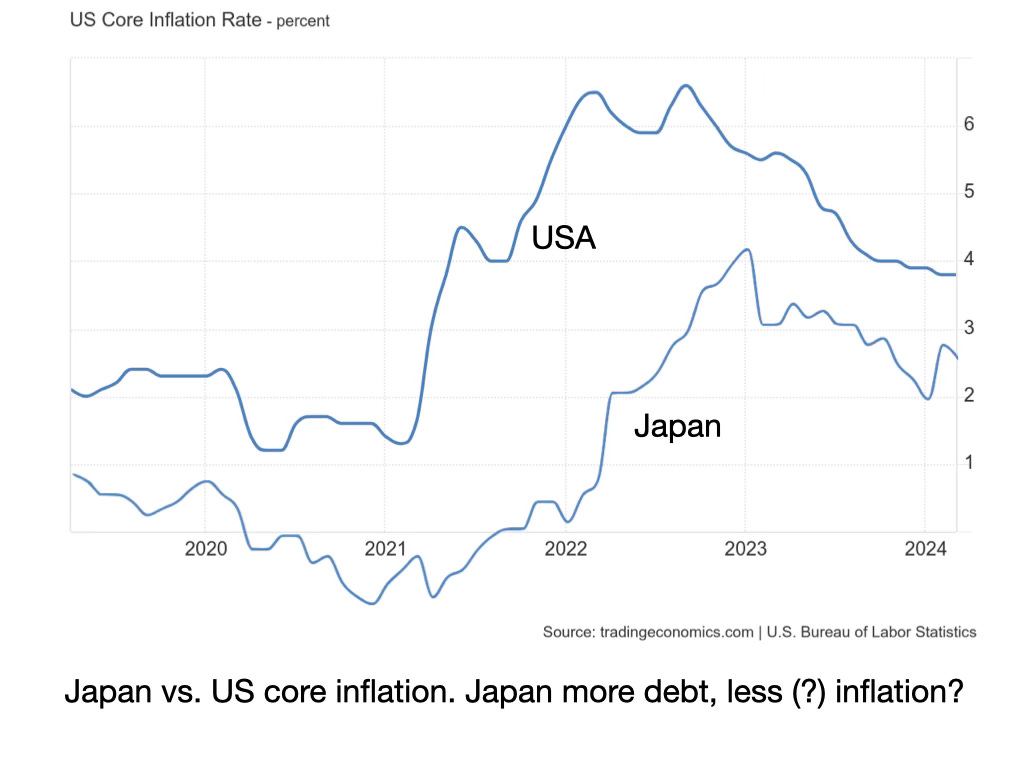

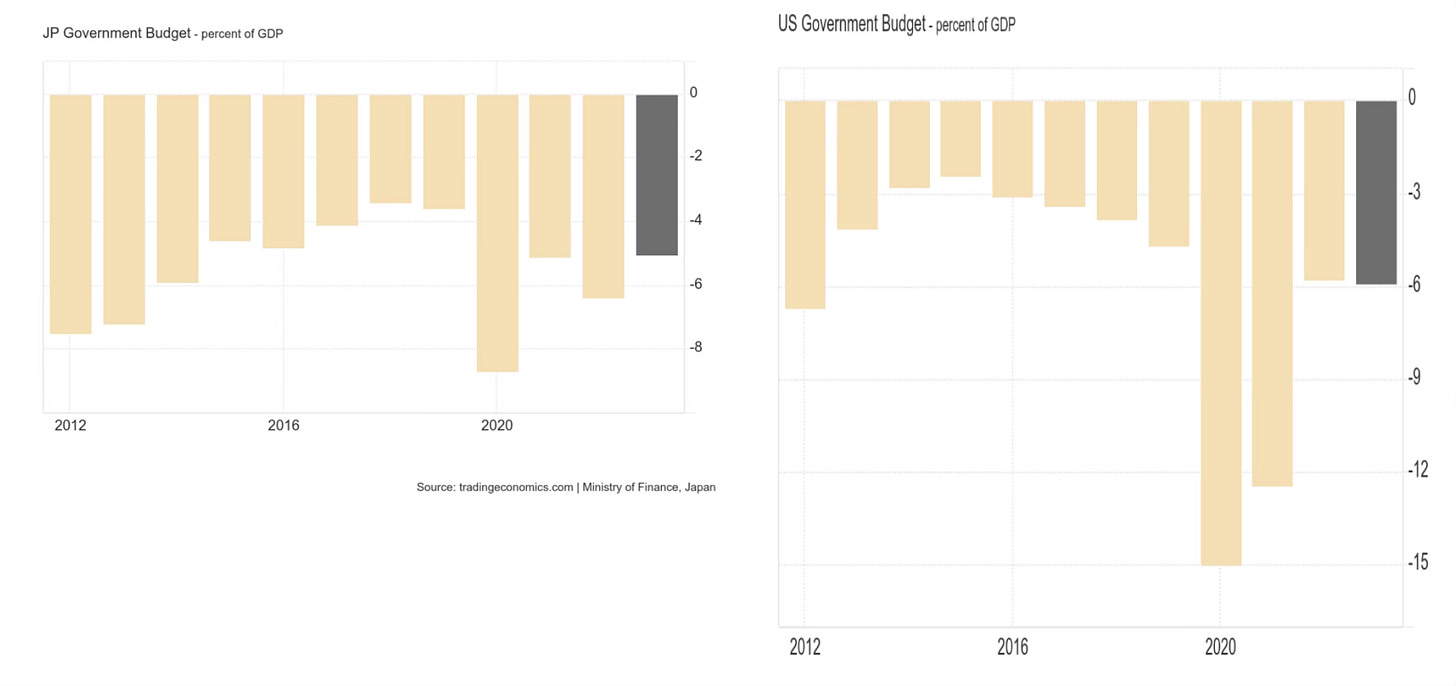

Japan has had less inflation than the US in this episode. Given Japan’s famous debt to GDP ratio, how can that be?

First, it’s not obvious that Japan really has had lower inflation than the US. Japan’s inflation started later, but also peaked later. The unexpected rise of inflation, and hence what fraction of debt was inflated away is actually about the same. But different measures differ, and we can at least ask why Japan’s inflation was not much worse.

In the simplest case, flexible prices and short-term debt, fiscal theory states

Unexpected inflation is equal to the change in expected surpluses divided by initial debt. With sticky prices and long-term debt, this describes the overall price level increase in the episode.

So, why might a country have less inflation than another?

First, obviously, a country might have less deficit, the initial series of negative s_t+j.

Second, a country might promise to repay more of that deficit; the same initial negative s_t+j might be paired with greater subsequent positive s_t+j.

When we expand the model to include time varying interest costs (important!), subsequently lower interest costs have the same effect as higher subsequent surpluses.

Third, and most importantly, more debt B means the same stream of deficits and surpluses s generates less inflation.

Read that again. Yes, more debt means that deficits have less inflationary effect. At 100% debt to GDP, 1% inflation inflates away 1% of GDP debt and pays for a 1% of GDP unfunded deficit. At 200% debt to GDP, 1% inflation inflates away 2% of GDP debt, and pays for 2% of GDP unfunded deficit; equivalently, 0.5% inflation inflates away the same 1% of GDP unfunded deficit. A $1000 loss lowers Tesla’s stock price by 1/557,160,000. It lowers the value of a $2,000 food truck business by 50%.

Your intuition that more debt must be dangerous for inflation reflects the correct intuition that more debt relative to GDP means that the government is closer to its fiscal limits, so that raising surpluses might be a lot harder. Countries with lower debt and more fiscal space find it easier to promise surpluses to fund a given deficit. But for a given path of surpluses, more debt means less inflation.

So, why did Japan have less inflation (if it did)? Well, first of all, Japan ran deficits about half the size of the US in the pandemic.

Second, looking across countries, Barro and Bianchi (2024) find that covid-era inflation lines up beautifully with deficits scaled by the value of debt. Barro and Bianchi also correct for duration. Longer duration like stickier prices allows a given surplus shock to be reflected in inflation that occurs after the 2020-2022 window. Japan lies comfortably on the line linking the other countries.

That all countries lie on a line with a slope of about half means that all countries are expected to repay about half of their covid deficits. Variation in that fraction is one source of variation of countries about the line.

In sum, reading Barro and Bianchi, Japan had less inflation in 2020-2022 because it did less covid spending, because it had much longer-term debt than other countries allowing 2023 and further on inflation to devalue some of its debt, because it has a lot more debt in the first place, and, slightly (deviation from the line) because Japan is expected to pay back a slightly larger fraction of its covid era spending.

(See the next post for Part 4, Japan’s central experiments.)

The incentive picture doesn’t include the stick, the negative incentive, tho we all like more positive carrots. Regulations, and laws & business norms, include lots of penalties, which are both microeconomic incentive structures, and sticks.

Great new point about how a larger debt is a bit anti-inflationary due to 1% inflation reducing a higher amount of debt value. 2.5% for a Japan with 250% debt/gdp ratio.

Typo: shrinkflation, not shrik.