Inflation and the Macroeconomy

These are my prepared comments for the session “Inflation and the Macroeconomy” at the 2025 American Economic Association annual meetings, with Jason Furman, Ben Bernanke, and Christina Romer. You can watch the session here with the other thoughtful presentations, and a lot of good back and forth. Interspersed are some slides, which Jason wisely nixed. Jason asked us to think about three questions:

1. The Past: What explains the inflation we experienced? Did fiscal policymakers or the Fed err, and if so how can the Fed avoid repeating the mistake? Why did so many forecasters miss it?

I’ll base my comments on several essays, available on the “fiscal theory” tab of my website, in particular “fiscal narratives” and “expectations and the neutrality of interest rates”

There are three puzzles, really. Why dd inflation break out suddenly in February 2021? Why did inflation peak, and then ease June 2022, while the Fed Funds rate was still 1.5%, with no unemployment or recession, no repeat of 1982? Why is inflation stuck around 2.5%?

It’ not a puzzle. This episode neatly fits two of the most classic stories, that we routinely tell undergraduates.

War finance. In a war, governments spend like crazy. Central banks monetize debt, and hold interest rates down. Inflation predictably breaks out, creating a Lucas-Stokey state-contingent default. Holders of outstanding bonds pay for a lot of the war spending.

That’s exactly what happened. The primary deficit touched 25% of GDP. Government debt in private hands rose $5 trillion during Covid, and another $4 trillion since. The Fed monetized $3 trillion of that debt, and kept interest rates at zero for an unprecedented year even as inflation surged. Borrow and print money, send people checks. Is it a mystery why we had inflation?

This is a totally standard story. It happened in most of the major wars since the 1700s. It explains why inflation broke out, but it also explains why inflation eased without high real interest rates or a recession. A one-time fiscal shock gives rise to a one-time rise in the price level. (I owe a lot to George Hall and Tom Sargent, and to Jim Bullard for this analogy.)

There is nothing specially fiscal theory in this story. Fiscal theory emphasizes an aspect that is true in all models, however: debt and deficits only cause inflation when people do not expect the new debt to be repaid by higher future surpluses. Debt that will be repaid doesn’t cause inflation.

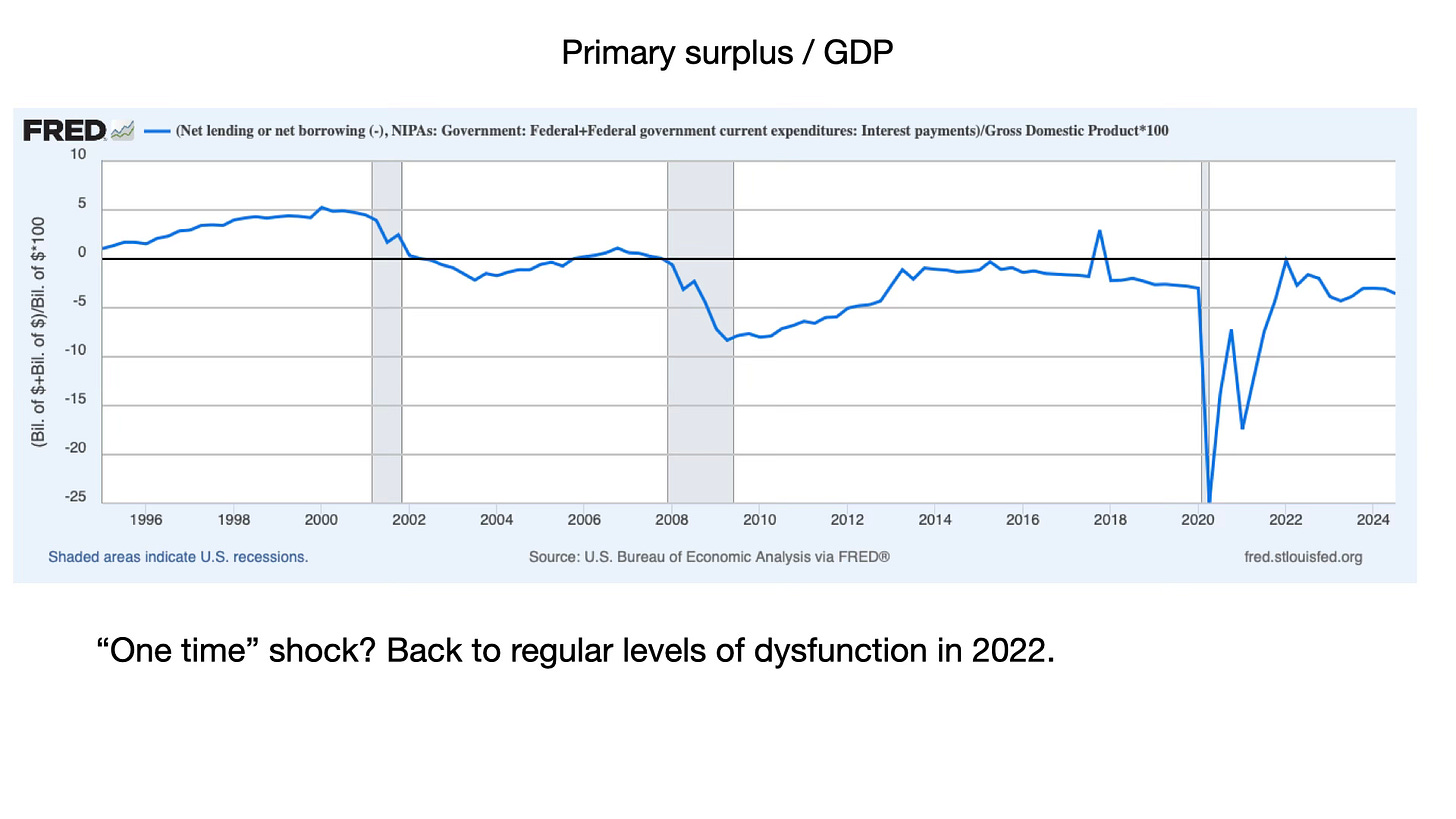

That fits too. This spending binge was much more devoid of promises to repay than, say, 2008. Moreover, the huge spending packages of early 2021, when Covid was over, signaled that the US was not going back to normal fiscal policy and slow debt repayment. That’s just when inflation surged. Inflation ended in summer of 2022 as it became clear that there would be no $6 trillion green new deal, and now we are going back to normal levels of fiscal dysfunction. The primary deficit even briefly hit zero in 2022, and is now back to its pre-2020 levels.

This is also why inflation is hard to forecast — even a classic fiscal inflation, and even my me. It’s hard to know how much faith people have that debt will be repaid.

A one-time unfunded fiscal shock produces a one-time rise in the price level, an inflation surge that can go away on its own. That otherwise puzzling easing is even clearer evidence for this story. Raising interest rates helps bring down inflation more quickly, but at the cost of somewhat more persistent inflation, just as we are seeing.

None of this is necessarily criticism. The Lucas-Stokey state contingent default is an optimal response to a big enough crisis. I don’t think it was, because I think the spending was overdone for the nature of the crisis, but that’s a question of size not mechanism.

Supply shocks

What about supply shocks? That’s another standard parable that everyone seems to be forgetting.

There were supply shocks in the pandemic. Businesses were locked down. We couldn’t get TVs through ports. There were “relative demand” shocks too. People wanted Peletons, not restaurant dinners.

But supply and relative demand shocks are temporary shocks to the level of relative prices. Temporary, level, relative. Rule 1 of macro: Do not confuse relative prices with the price level. Rule 2: Do not confuse the price level with the inflation rate.

Peleton prices must go up relative to food, or wages. And once it’s over, Peleton prices go back down again. That does not explain why all prices go up, and stay there.

A supply shock only causes inflation, a rise in the overall price level, if it is accommodated by monetary and fiscal policy. Inflation is not the sum of relative price changes. It is a decline in the value of money. Loosely, people cannot pay higher prices for everything unless the government gives them the money to do it.

This is true in all models, and in particular the models being used to decompose the source of inflation to supply and demand shocks, misleadingly in my view. Look hard for the nominal anchor. Deep in the footnotes, you will find that the supply shock induces an expansionary monetary or fiscal policy. Without that expansion, no inflation. Supply shocks are the carrot, monetary and fiscal policy is the horse, and inflation is the cart. It makes no sense to say “carrots moved the cart.”

This is also not necessarily criticism, and inflation not necessarily a mistake. The Fed and fiscal authorities think downward price movements hurt more than upward price movements. They choose to accommodate with more inflation. This is the standard story of the 1970s oil price shocks. That is the standard advice given to governments to inflate and devalue in the face of terms of trade shocks.

Really this is the same story. Our government including the Fed responded to the pandemic, and consequent supply and relative demand shocks, with a massive fiscal-monetary accommodation.

Puzzle

Why is this at all controversial?

Some part of it is surely our policy maker’s realization that they did overdo it, and consequence reluctance to take responsibility. They should say “Yes. We faced the pandemic and its aftermath with $9 trillion of vital extra spending. We took most of that out of the pockets of government bond holders with a 20% haircut via inflation rather than raise taxes for a generation. We faced supply and relative demand shocks, and chose to make all prices rise rather than some, and especially wages, decline, which we thought would cause a recession. You’re welcome.”

Instead, a dog-ate-my-homework attitude pervades: Some nebulous shock hit that we couldn’t do anything about - supply, relative demand, or price gouging, monopoly, greed, hoarding, and other silliness we hear from politicians.

They must feel that it the accommodation was, indeed a mistake.

Another part, I think, was a conceptual mistake, revealed in part by the mistaken forecasts at the time. I think a lot of people forgot these two standard undergraduate stories. Central banks were not looking for “supply shocks,” and felt even thinking about fiscal policy to be impolite. Both monetary and fiscal policy mistook a negative supply shock for inadequate demand, and applied inappropriate fiscal stimulus: helicopter money, not targeted insurance. The fiscal zeitgeist was secular stagnation, hysteresis, deflation fears, r<g, MMT, “go big,” “savings gluts,” safe asset “shortage” advice that prosperity just needed us to print $5 trillion and hand it out. Well, we did what they asked. Now I hope we know better.

We will have more shocks, tempting fiscal and monetary accommodation. If we are not proud of this inflation, being honest about what happened is the necessary first step to not repeating it in the next shock..

2. The Present and near future: where are we now? Will inflation die out or resurge, like the late 1970s? How might Trump tariff, immigration, deregulation and fiscal policies affect inflation? How will / should the Fed react to those?

I don’t like to forecast, because it’s easy to be wrong. Also, modern macro tells us that inflation is a bit like stock prices. If businesses could forecast that prices would go up next year, they would raise prices now. Hence inflation will always be somewhat unpredictable.

The expected path is pretty benign. We are in the late summer of the business cycle, and will trundle along until the next shock hits, assuming the Fed doesn’t do anything really dumb. Which I don’t think it will. Most of what happens to inflation depends on what shocks hit, and how our policy makers react to them, not whatever conditional mean dynamics one can reliably foresee.

I think the “tariffs are going to cause inflation” line is overblown. Tariffs are a relative price shock. Did I mention not to confuse relative prices with inflation? Again, inflation is not the sum of a thousand relative price increases and decreases. Inflation always and everywhere comes from monetary and fiscal policy, directly or from accommodation.

So the effect of tariffs also depends entirely on the fiscal / monetary accommodation. The effect of tariffs also depends on the exchange rate. With the right elasticities, tariffs can cause the exchange rate to rise just enough to negate the tariff.

Tariffs are a corporate tax on imports, partially passed on to consumers. Corporate income taxes are also partially passed on to consumers. You can’t bemoan the inflationary effect of tariffs and deny the same effect of corporate taxes. Corporate taxes are certainly not going to be as high as they would have been under Harris, so that will have the opposite effect. And as a reminder, the US had deflation in the late 1800s, and grew despite (yes, despite) tariffs. The US had deflation in the 1930s under Smoot-Hawley. So I don’t see a big effect.

But in both cases, I think it’s a mistake to focus on inflation. Evaluate taxes by their revenue and real distortionary effects. Evaluate immigration, deregulation, and other policies for their microeconomic benefits and costs. If you don’t like them, don’t fight bad policies for the wrong reasons.

However I do have to put on my fiscal theory hat a bit. Fundamentally, inflation comes from debt we won’t or can’t repay. Long run tax revenue is good for inflation, but that mostly comes from more growth not higher tax rates. So microeconomic distortions, or their removal, can affect inflation. But these are long-run questions, not inflation-next-year questions.

The underlying fiscal situation is not good. The 10 year rate is wandering up, and there is a small chance that a flight from sovereign debt and inflation breaks out without a spark. The moment I give up worrying about that is probably when it will finally happen. But I think the real danger is, what is the next big shock? I’ll hold that for Jason’s next question about the future and bank my time.

3. The Future: what are the lessons, particularly for the framework review? What other policies (fiscal, financial) should the US pursue to reduce the risk of inflation?

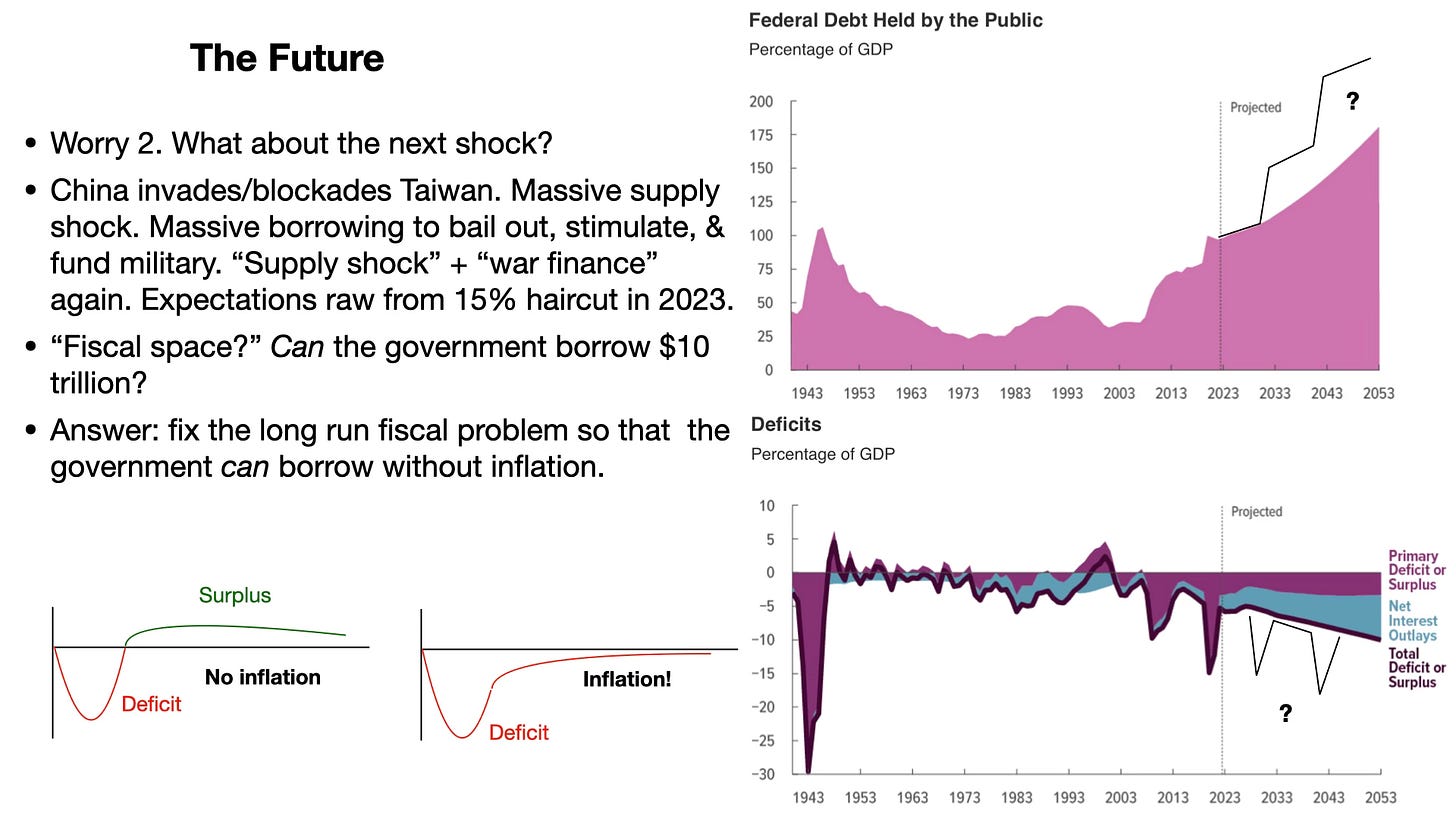

The biggest question for inflation, in my view, is how we will react to the next shock. Bird flu could break out and be much worse than Covid. China could blockade Taiwan, provoking a catastrophic global trade, supply, and financial meltdown. A severe global recession could break out.

What happens then? Uncle Sam will come knocking for $10 trillion. To address the crisis; to bailout the financial system; to support people and businesses in trouble; for stimulus; and maybe a big military expense.

Is there really another $10 trillion of saving, wiling to hold government debt and not try to spend it? Bond markets will say, "we just paid a 20% haircut. Again? With Social Security, health care, and spending ratholes unreformed, how do you plan to repay this new debt?” Inflation expectations are primed by recent memory. The Fed will be pressured to buy all the new debt again, and hold down rates so the government can borrow cheaply. And Inflation could be the least of our problems. What happens when the US and other governments are unable to raise what they need?

So what do we do? Above all, stop goofing around about what happened last time. If nebulous dog-ate-why-homework it-wasn’t-our-fault shocks excuse 10% inflation, then we are doomed to regular bouts of inflation any time those shocks recur. Which they will. If you believe those stories, then you believe that American institutions that define the value of our currency have a fundamental, unfathomable flaw that will produce regular bouts of uncontrollable inflation.

No. Inflation is a choice. If we don’t want inflation, we have to make different choices.

First, if the 2021-2023 inflation was a mistake not an optimal state-contingent default, then spend more effectively in the next crisis.

Second , we need to match borrowing with credible promises of future surpluses to repay debt, so that the debt we do issue is not inflationary. The best promises are encoded in time-consistent institutional commitments.

Third, don’t monetize it. The Fed needs to prepare to allow long term rates to rise without buying trillions of treasury debt, and prepare to promptly raise short term rates, even though the Treasury will be screaming otherwise. The Fed did not use an ounce of its storied independence to fight this inflation. It will need battle plans if it wishes to fight the next inflation.

The Fed must also solve “financial dominance.” If the Fed raises rates, bank assets and corporate bonds will fall, which the Fed did not countenance last time. Bailout-hungry institutions will scream “systemic risk,” “market dysfunction,” “prop up our assets.” If the Fed wants to fight inflation with higher rates, it needs to get over-leveraged Fed-put dependent financial institutions out of its way. Regulatory reform is an inflation fighter.

Fourth, if the Fed does not want to meet relative price shocks with inflation, it needs to allow some prices to decline. Maybe price or wage declines are not so bad after all. More deeply, if we fear downwardly sticky prices and wages, make prices and wages less sticky — or at least remove layers of law and regulation that make them stickier. That’s microeconomic and regulatory reform, but it’s the key to allowing relative prices shocks to once again be relative.

Finally, even if the Fed has the capacity to see the next shock, and the desire and will to fight it, can the Fed do it?

We have 100% debt to GDP ratio. Every 1% that the Fed raises real interest rates means 1% of GDP greater interest costs on the debt. In every model of inflation, fiscal policy tightens, now or in the future, to pay these extra interest costs. That’s often off in some footnote about lump sum taxes and “passive” fiscal policy, but it’s there. But imagine that the Fed tells Congress, “we need 1980s levels of real interest rates. You need to provide 3% of GDP fiscal tightening?” I can hear Congress laugh.

In every model we have, if Congress does not or cannot pay the extra interest costs, higher interest rates raise inflation. Without fiscal tightening, the Fed cannot lower inflation via higher interest rates. (See “expectations and the neutrality of interest rates” for calculations to support this point.) This has happened over and over in failed inflation stabilizations around the world.

My main fiscal worry then is the lack of fiscal space: Space to borrow to finance the next shock, space to pay extra interest costs on the debt to fight the next inflation.

Putting the fiscal house in order is both easier and harder than it sounds. The key issue is to restore faith in decades of small primary surpluses that can pay off debt. This year’s deficit matters little. Permanent tax, spending, and entitlement reform, and growth-oriented microeconomic reform matter more than the usual fiddling with tax rates. As an extreme example, falling birthrates matter to long run debt repayment, but not to next year’s deficit.

As you can see, my two stories emphasize a hard reality. Inflation was not a “mistake,” interpreted as a technical failure that can be fixed with a tweak to the FRBUS forecasting model, another few pages of sleep-inducing prose in the next strategy review, a few more twists in the Taylor rule. Inflation was a choice, a hard choice, of how to meet a huge crisis and big microeconomic shocks. If you don’t want inflation, you need to face this reality and think about how to make different, equally hard choices, in the next crisis. And it’s not just the FOMC deciding whether to raise or lower the overnight rate a bit more or less. Avoiding inflation in the next crisis means a profound change in how fiscal, monetary, and financial regulation approach that event.

In all this, I think we need a change in attitude. The Fed targets the forecast. We and the Fed need to think much more about how the Fed, and fiscal policy, will react to uncertain events. The Fed stress tests banks to see how they will react to shock scenarios. The Fed should stress test and war game its own policies.

These issues are an order of magnitude larger than the current framework review, but I close with a few comments about that.

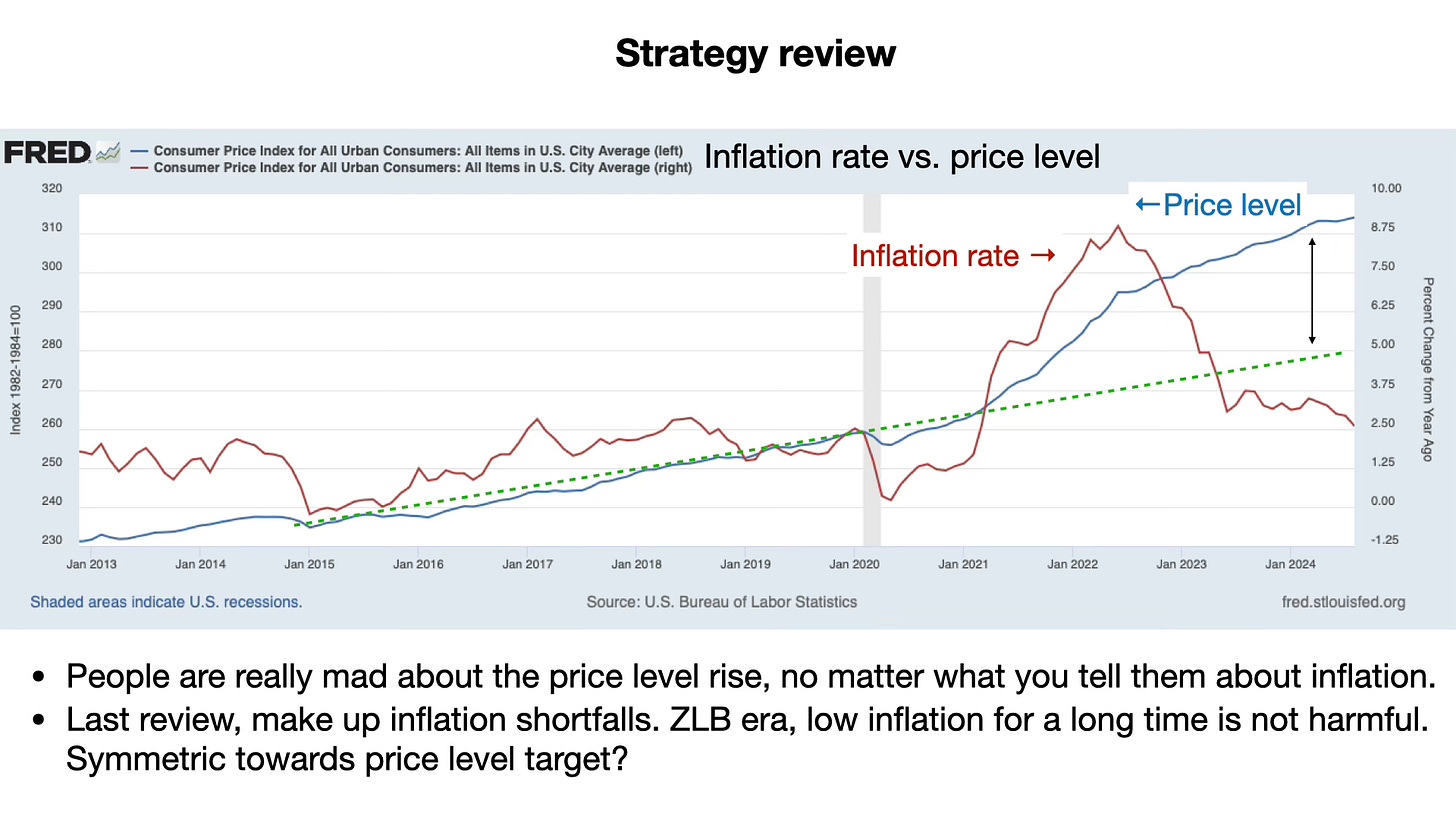

Inflation has reminded those who forgot another timeless lesson: People are really mad about the price level. Telling them that “inflation was transitory” so take the pitchforks home did not help. The zero bound era taught the lesson that “deflation spirals” are a myth and fear of low inflation unwarranted. So, as the old framework promised to make up past shortfalls of inflation with higher future inflation, perhaps the new framework should make up for past overshoots with future undershoots, to bring the price level back at least somewhat towards its previous trend. “Price stability” in the Fed’s mandate does not necessarily mean 2% inflation forever, and forgetting past mistakes.

People of modest means are also hurt by inflation. As one apocryphal commenter put it, “if there’s unemployment one in 10 lose a job. But we are all hurt by inflation.” Perhaps the doves should become a big more hawkish.

The last strategy review fought the last war with a beautiful new-Keynesian Maginot line against deflation at the zero bound, fought with promises of future largesse. And much of the point of any public strategy is to produce recommitments that line up expectations, faith that the Fed will not let things get out of control. So the next review should emphasize instead how the Fed will react to shocks, and it’s “whatever it takes” determination.

Update:

Ed Nelson, author of the magisterial Milton Friedman biographies, passes along the following quote from Milton and Rose Friedman, The Tyranny of the Status Quo, 1984, p. 84

Inflation refers to the price level in general, not to the prices of particular goods and services. Higher oil prices may lead people to spend more money on oil. But if so, they have less to spend on other goods, which leads to downward pressure on the prices of those goods. The downward pressure offsets the general upward pressure on oil prices, so that the price level in general need not be affected. However, most prices are slow to adjust. Hence a sudden upward jump I the price of a product that is widesly used, such as oil, may temporarily raise the level of inflation before the offsetting toward pressure becomes effective That tagging behind events is the element of validity in the argument that rises in particular prices cause inflation.

How “supply shocks” operate really was standard stuff once upon a time. New-Keynesian models slip the nominal anchor — money supply in Friedman’s case — into footnotes which may be how people fail to see it. A Phillips curve shock raises inflation, but you have to look at the footnotes to see how either money or fiscal policy accommodate that inflation.

Ed also passed on a really good speech from Ben Bernanke, “‘Constrained Discretion’ and Monetary Policy” Before the Money Marketeers of New York University, New York, New York February 3, 2003.

The primary cause of the Great Inflation, most economists would agree, was over-expansionary monetary and fiscal policies, beginning in the mid-1960s and continuing, in fits and starts, well into the 1970s….

You may have noticed that I have discussed the Great Inflation of the 1970s with an emphasis on Federal Reserve behavior but without mentioning oil prices. My reading of the evidence suggests that the role the conventional wisdom has attributed to oil price increases in the stagflation of the 1970s has been overstated, for two reasons….

without Fed accommodation, higher oil prices abroad would not have translated into domestic inflation to any significant degree.

Ben’s view that “supply shocks” did account for inflation in 2021-2023 is not inconsistent. He alluded basically to a Phillips curve analysis suggesting this time is different. (I disagree. Maybe I’ll follow up on that later.) But it’s nice to see such a clear statement of the conventional view.

This is great. Clearer than the average economics tract. And clearly lays out the real problem - long term fiscal dysfunction. If only economists could fix fiscal dysfunction.

You say deflationary spirals are a myth, but I think Ben could have easily replied that they one didn’t occur after the 2008 recession because of the monetary and fiscal response.