Fiscal Tidbits, part 2

(This continues “fiscal tidbits.” The post got too long for substack. Tidbits are turning into a banquet.)

Supply shocks?

Where did the 2021-2023 inflation come from? Leaving aside silliness such as “greed,” “monopoly,” “price-gouging,” and “shrinkflation,” the serious debate is between “supply shocks” and “relative demand shocks” (more goods, less services) vs. fiscal excess. As blog readers will know, my view is that it’s fiscal excess.

“Supply” and “relative demand” shocks, in my understanding, suffer because they generate a transitory change in relative prices, not a permanent change in the price level to say nothing of the inflation rate. If you can’t get TVs through the ports, the price of TVs has to rise relative to the price of restaurant meals, and to wages. That does not explain why all prices go up, including restaurant meals and wages; why the value of the currency declines. Moreover, once the ports unclog, the price level returns, meaning not just transitory inflation, as supply-shockers assert, but a period of deflation matching the initial inflation to bring the price level back. See the first, left option below.

It seems to me that for a relative price shock to raise the overall price level, you need demand; either monetary or fiscal policy. And then it’s really the monetary and fiscal policy that’s raising the overall price level.

Now, yes, central banks and governments may well respond to a relative price shock with monetary or fiscal policy that raises the overall price level. They might choose option 2 or 3 in my little schema, not option 1. They don’t like any prices to go down, especially wages, and view that option 1 might cause a recession that option 2 and 3 would avoid. That’s a conventional reading of how “oil price shocks” caused inflation in the 1970s — they induced expansionary responses.

But if the inflation is due to the monetary and fiscal policies, which respond to the relative price shock, does it really make sense to say that inflation is not due to the monetary and fiscal policy, but “due to” the supply shock? The supply shock is the carrot, in front of the horse (monetary or fiscal policy) that pulls the inflation cart.

Why not go one step deeper, and say it’s a “pandemic shock” that caused the inflation? Or a “lab accident shock?” That’s clearly not very illuminating as to the economic mechanism. If we want to say “supply shocks” or “relative demand shocks” caused inflation, we should pull out the endogenous response of monetary and fiscal policy.

And yet good papers estimate supply vs. demand shocks for the covid inflation and find evidence for supply shocks. What gives?

Two particular papers caught my eye, Fiscal Backing, Inflation And US Business Cycles by Frank Smets and Raf Wouters, presented at the Hoover Economic Policy Working Group, and Quantifying Fiscal Policy’s Role in U.S. Inflation by Nathan Balke and Carlos Zarazaga. Both of these papers specify a Smets-Wouters style new-Keynesian model, expanded to include fiscal theory and the possibility of fiscal shocks. (Standard new Keynesian models assume fiscal policy always repays deficits, so there is no such thing as a fiscal shock.) Bravo! This is just the kind of extra realism that I have hoped people would work on.

But they both find an important role for “supply shocks.”

Now, part of the problem is linguistic. My microeconomic interpretation of “supply” shock is not what people think about in terms of these models. In a typical new-Keynesian model, (simplifying a lot) a key ingredient is the Phillips curve

Inflation equals expected inflation, discounted a bit less than one, plus a coefficient times “marginal cost,” which is output plus a “marginal cost shock,” plus an additional shock v. (The marginal cost shock can appear in either place.)

In this schema a “supply shock” is a movement in u or v. And you see that it translates directly into an increase in inflation pi. At a minimum the price level goes up like my middle example. Additional model dynamics can lead to more inflation, like my third example, or worse.

How do we reconcile these two views? I puzzled a lot, and asked Frank. He had a super clear answer: If you look deep in new-Keynesian models, there is a money supply which anchors the price level via MV=PY. (Mark Gertler’s excellent notes make this point.) The interest rate target thus implies a money supply expansion in response to the Phillips curve “supply” shock. I would add fiscal policy. Even if MV=PY controls the price level, the unexpected inflation devalues government debt, which leads “passively” to deficits. I read the same outcome as the deficits directly respond to the supply shock. And my totally cashless alternative (and observationally equivalent) foundation for new-Keynesian models doesn’t have money at all.

In sum, even new-Keynesian models, in which it looks like Phillips curve “supply” shocks directly raise inflation, actually get that inflation from an endogenous monetary and fiscal response, not from the supply shock itself. So, I still don’t think it’s fair to say that these calculations tell us how much “supply shocks” rather than “monetary or fiscal policy” contributed to inflation. It’s all monetary and fiscal policy. They tell us why our authorities chose expansionary monetary and fiscal policies.

Also, look at the whole model, including the footnotes, not just one equation!

The Shekel as a tech stock

This is a slide presented by Amir Yaron, governor of the Central Bank of Israel, at the Hoover Monetary Policy Conference. The blue line is the Shekel-Dollar exchange rate. The green line is the Nasdaq. The orange line is the fitted value of a regression of the exchange rate on the Nasdaq. The point: The Shekel is valued like a growth-oriented tech stock. I’m starting to try to think of exchange rates in FTPL terms, and this seems like a lovely such interpretation.

(Yaron’s point was that the Judicial reform lowered international confidence in the Shekel and drove the exchange rate away from its usual fundamental. He also went on to talk about monetary policy in a terrorist attack and war, and how small open economies adapt monetary policy to exchange rate concerns.)

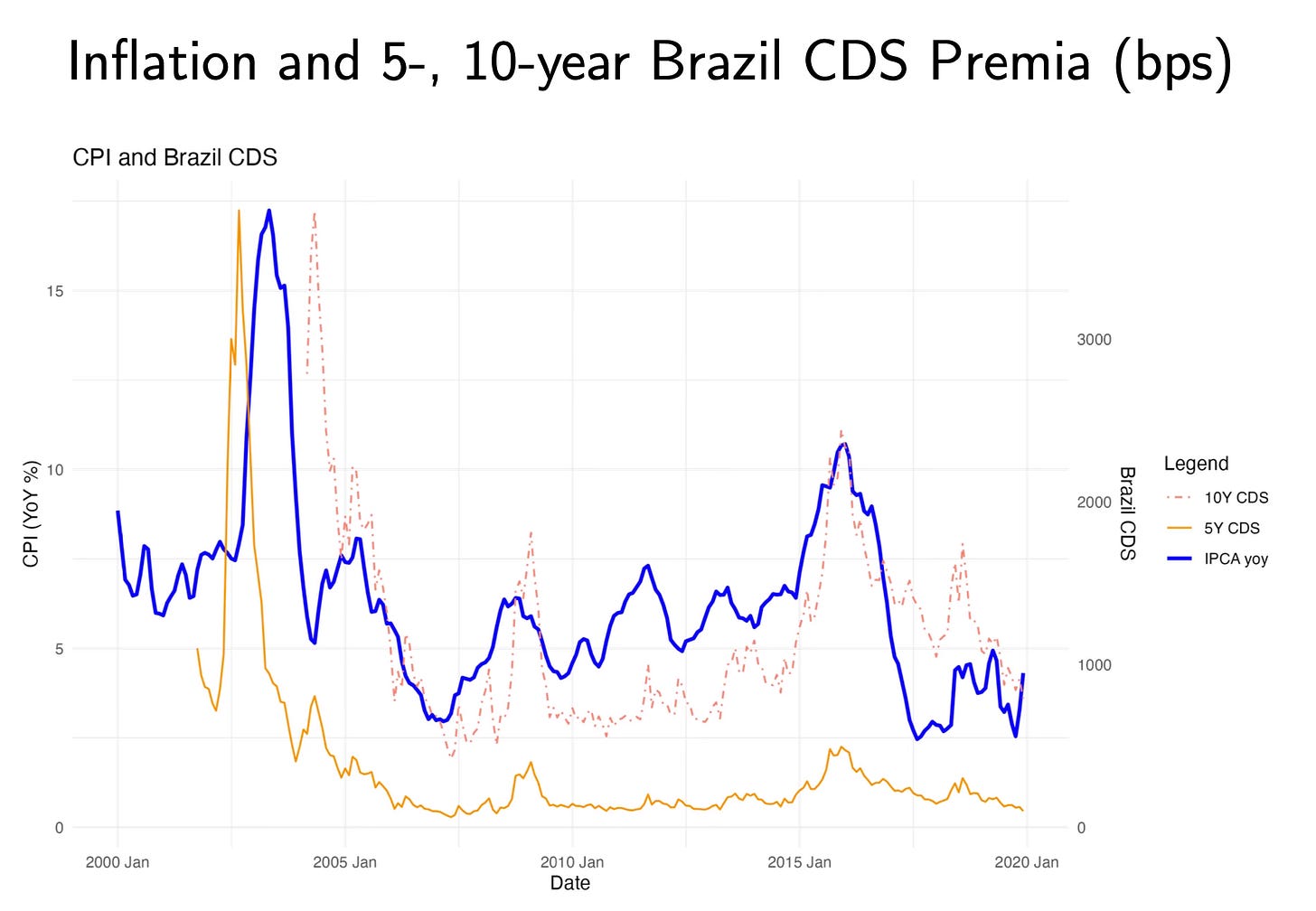

Brazilian CDS

This graph was made by Pedro Carvalho, a Stanford senior who wrote a nice analysis of Brazilian inflation for a senior honors thesis, “Fiscal Sustainability and Inflation Dynamics: The Case of Brazil.” He uses CDS on Brazilian government debt as an indicator of fiscal stress. A greater chance of default is also a greater chance of future inflation, a sign of intractable deficits not credibly backed by future surpluses. The nice point of the chart, a rise in the CDS spread correlates nicely with surges in inflation. Pedro includes the CDS in a VAR, and uses CDS shocks to measure shocks to fiscal expectations, a very good idea.

For the benefit of casual readers.

IPCA is the benchmark inflation index observed by the Central Bank of Brazil.

If I understand your arguments correctly, you claim that the recent inflation was caused mainly by government intervention. You dismissed greedinflation as silliness. Given that high inflation also occurred in countries with small or no government stimulus, your conclusions are either wrong, or you should be able to explain inflation in those countries.