Euro Transfers

On Friday I had the pleasure of discussing a great new paper, “What does it Take? Quantifying Cross-Country Transfers in the Eurozone” by YiLi Chien, Zhengyang Jiang, Matteo Leombroni, and Hanno Lustig, at the San Francisco Fed Macro-Finance Conference.

Why me? Well, of course I’ve been working on the euro with coauthors Luis Garicano and Klaus Masuch, resulting in “Crisis Cycle,” our book about the euro.

Bottom line: The euro has become a vast fiscal transfer scheme, from country to country and to banks. The EMU is more of a fiscal union than you think! I add, it did so unwittingly, and we stress the poor incentives that these fiscal transfers induce. Reforms are pretty straightforward once you state the problem.

The tragedy, really, is that a transfer scheme cannot be a widespread common currency. It’s easy enough to have a common currency, as it’s easy enough to all use the meter. Other countries should want to join a common currency, up to the usual “optimal currency area” arguments. In my view, pretty much all small countries on the edge of the eurozone should want to join. But now signing up to measure the price of groceries in the same units as the countries next door means also signing up for this fiscal transfer and insurance scheme. Poland has no interest in mutualizing Greece, Italy, or now France’s debts.

Going forward, the ECB and many European pundits would like the euro to become a global currency, to challenge the dollar (and renminbi!) for exorbitant privilege. If the US thinks that printing money and sending it abroad in return for solar panels and iPhones is a terrible strike against the nation, Europeans are happy to take our place. If the euro were just a currency, aimed narrowly at a stable value, with a simple inter-bank payments system, that could be so. Alas, now you sign up for Target2, a fiscal transfer scheme, paying for a sovereign default, the chance of another big inflation if countries run in to debt problems, and extensive regulation, climate disclosures and more.

US economists, familiar with Fed operations, would do well to understand the quite different structure of the euro. The authors did a great job of unpacking this mysterious leviathan. It’s a big part of our book as well. There are surprising possibilities and dangers. I am grateful that Luis and especially Klaus explained all this to me. I would never have figured it out from the acronym-laden ECB documents as these authors seem to have done. Much of “crisis cycle” started with Klaus and Luis writing how something worked, me repeating “explain that really slowly using small words and no acronyms.” If I get any of this wrong, let me know.

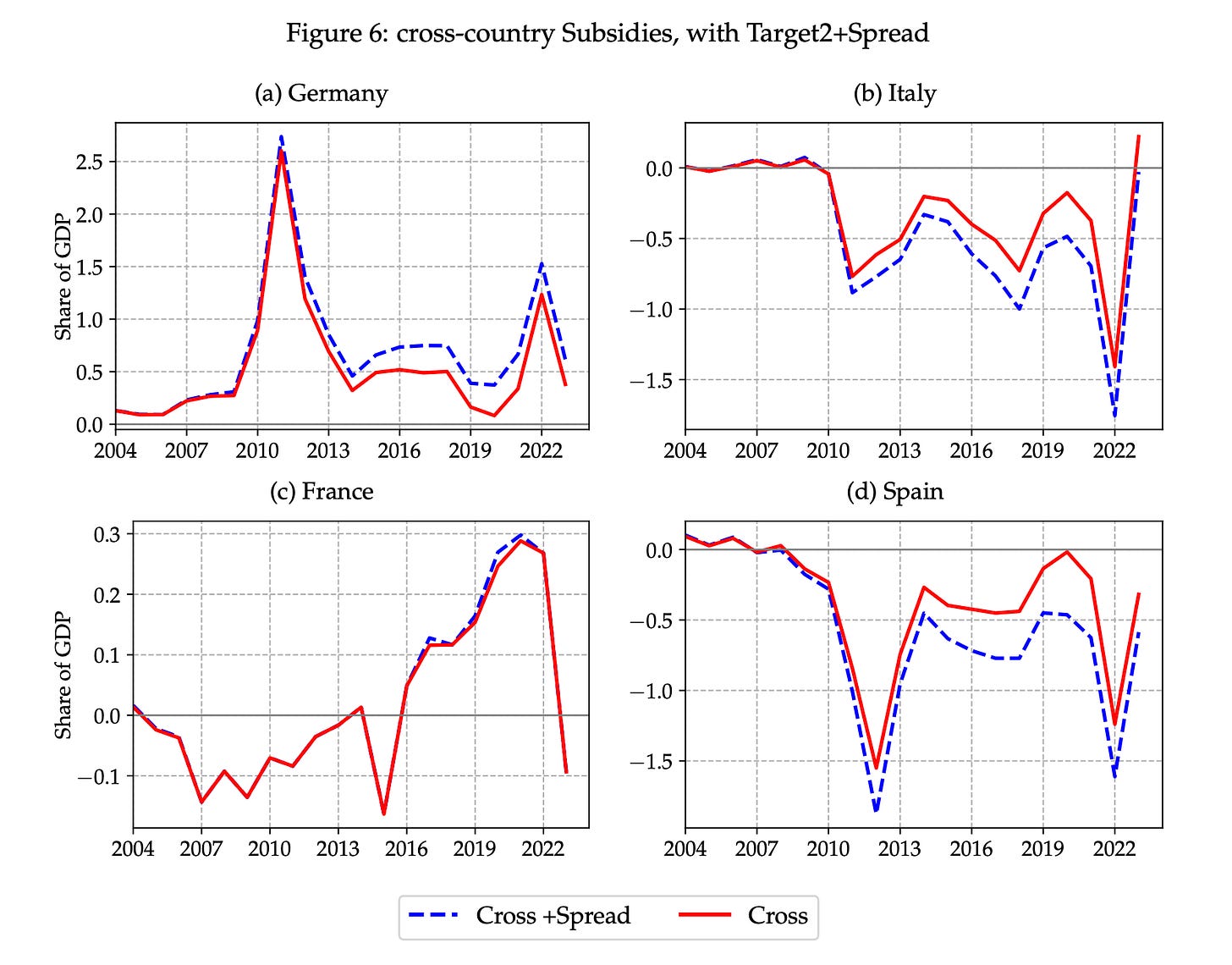

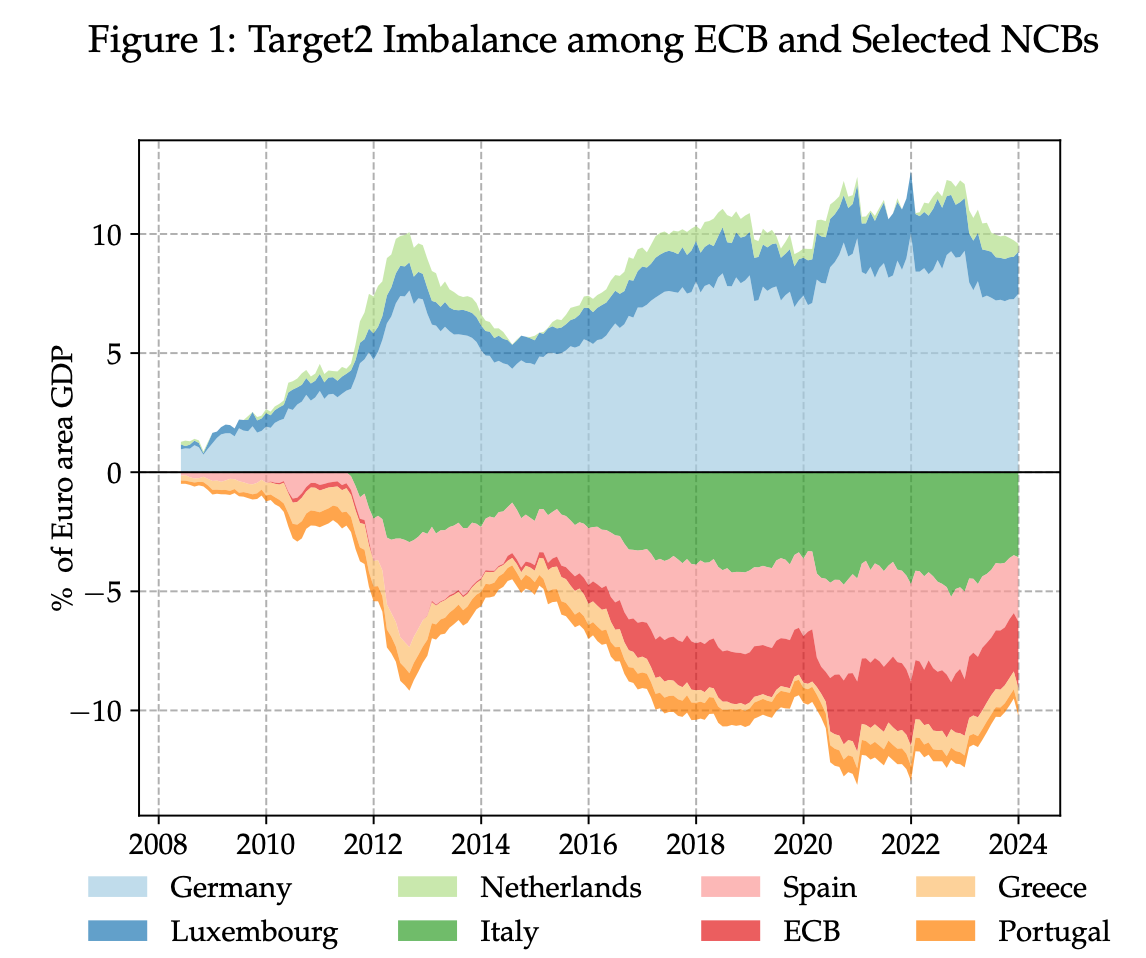

Here is one bottom line. “Within” is how much each national central bank subsidizes its banking system. “Cross” is how much fiscal transfer each country gives or receives to the others. Regular transfers on the order of 1% of GDP per year are nothing to sneeze at.

This graph compares what countries and banks get from the opportunity to borrow at ECB risk free rates rather than prevailing (sovereign) market rates. It does not include an estimate of how much the ECB pushed down sovereign market rates, which is another fiscal transfer. Adding an estimate of that spread compression makes it a bit larger.

The contingent transfers are larger. How much will it take to suppress a French debt crisis? How much will an exit cost?

So, what happened? The authors take an admirable just-the-facts approach, leaving hanging whether this fiscal transfer was by design, as one might regard agricultural subsidies and other EU spending, or an accident.

In our view, it was mostly an accident. The European Monetary Union was pretty well set up as a common currency with no fiscal transfers, in an era of small reserves, no interest on reserves, small sovereign spreads (sovereign default was “inconceivable,” as Vizzini might put it) and no ECB sovereign debt purchases. When, in response to unimagined crises, the ECB changed all that, these transfers erupted. (This story comes from “crisis cycle.”)

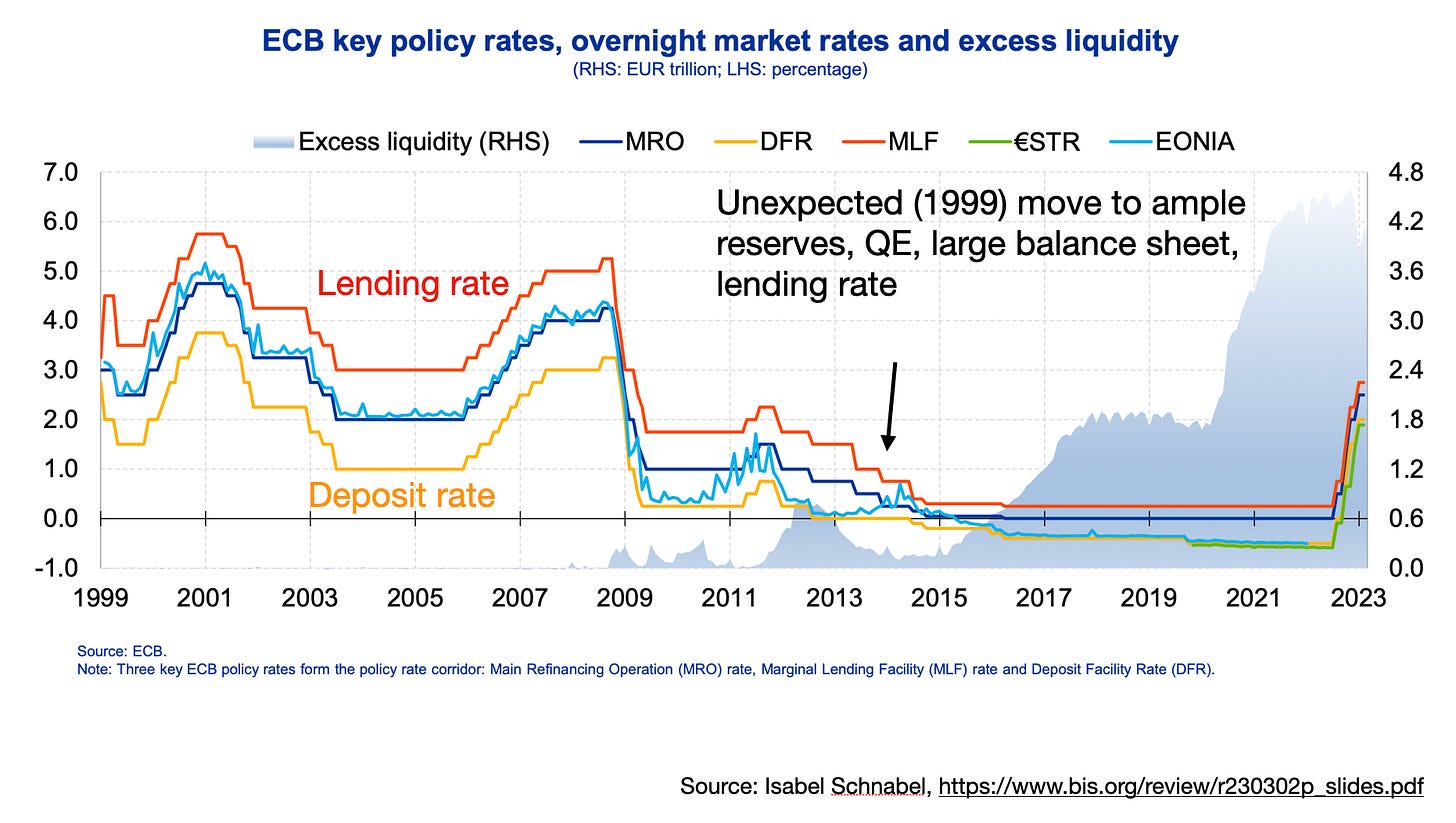

This graph (by Isabel Schnabel) illustrates the underlying situation. Before 2008, the ECB had essentially no assets and very small reserves (shadow, right scale). Amazingly (to US economists) the ECB did not buy assets to create reserves. It just lent money to banks, against high quality collateral, and counted the loan as the asset against the liability of money. Reserves did not pay interest, and banks held as little as possible, e.g. for reserve requirements against deposits. The actual overnight rate at which banks borrowed and lent reserves was halfway between the ECB’s overnight lending and deposit rates, at the weekly “main refinancing operations” lending rate.

Once the ECB moved to ample (!) reserves, far beyond reserve requirements (a good thing, I must repeat), which pay interest (if there is any), financed by quantitative easing purchases of sovereign and other bonds, we see the overnight rate drift down to the rate ECB pays banks on reserves, not the rate at which it lends to banks. That’s an indication that reserves are ample.

So what happened, unwittingly?

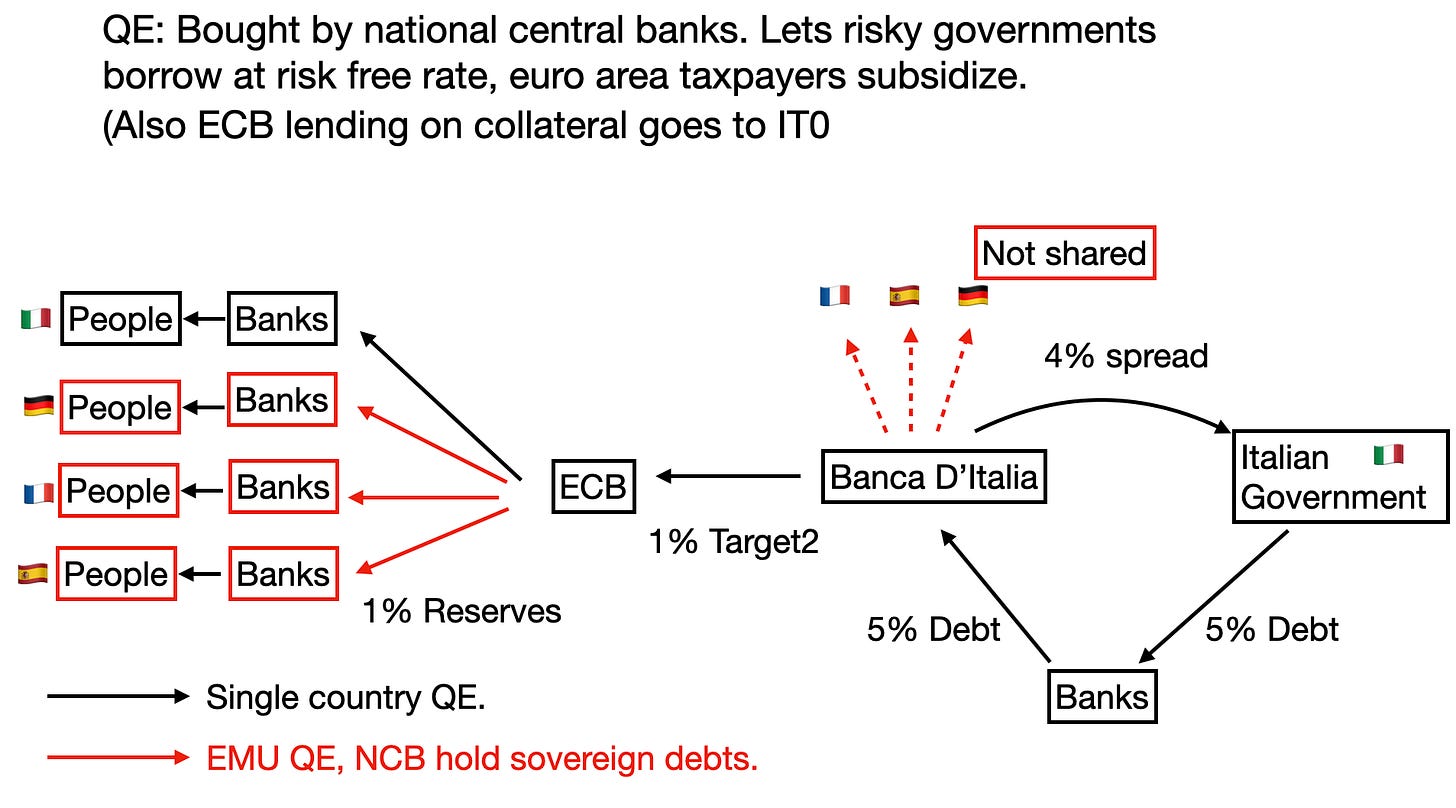

This graph (source, me) contrasts how QE works in a single country vs. what happens in the EMU. The Italian government borrows money, at (say) 5% interest, selling bonds to banks. Under QE, the ECB buys the debt from the bank. But (quirk #1) in the EMU it is not the central ECB that buys debt, as the New York Fed does. Each national central bank buys its own government debt. Furthermore, each national central bank shares its profits with its own government, and not the others. There are good and obvious political economy reasons for this setup, if you go back to the founding of the euro. It appears that Banca d’Italia holds the credit risk. Let’s not talk about the likelihood of a bailout from a defaulting government to its central bank. Now, the Banca d’Italia in turn borrows the money from the ECB via “target 2” balances, and the ECB issues reserves to banks and to people that are held throughout Europe.

The net result after the “profit” rebate to the Italian government is that, as long as Italy does not default on its debt, the Italian government gets to borrow at the 1% risk free overnight rate, not at the 5% sovereign debt rate. Nice deal! After all the various acronym-laden purchase programs, we’re talking about roughly 30% of Italy’s outstanding debt. With small initial sovereign debt holdings, mostly legacy debt from before the euro formation, this was not a big deal.

Target2, the accounting loans between ECB and national central banks, was designed for short-lived bank to bank transactions. It has turned in to permanent monetary financing. Nobody thought Target2 would be immense at the founding.

Governments (such as the US) that turn to their central banks for huge sovereign debt purchases also get a similar interest rate advantage, until inflation or default eliminate that advantage. But that is a transfer largely between their citizens, not from country to country.

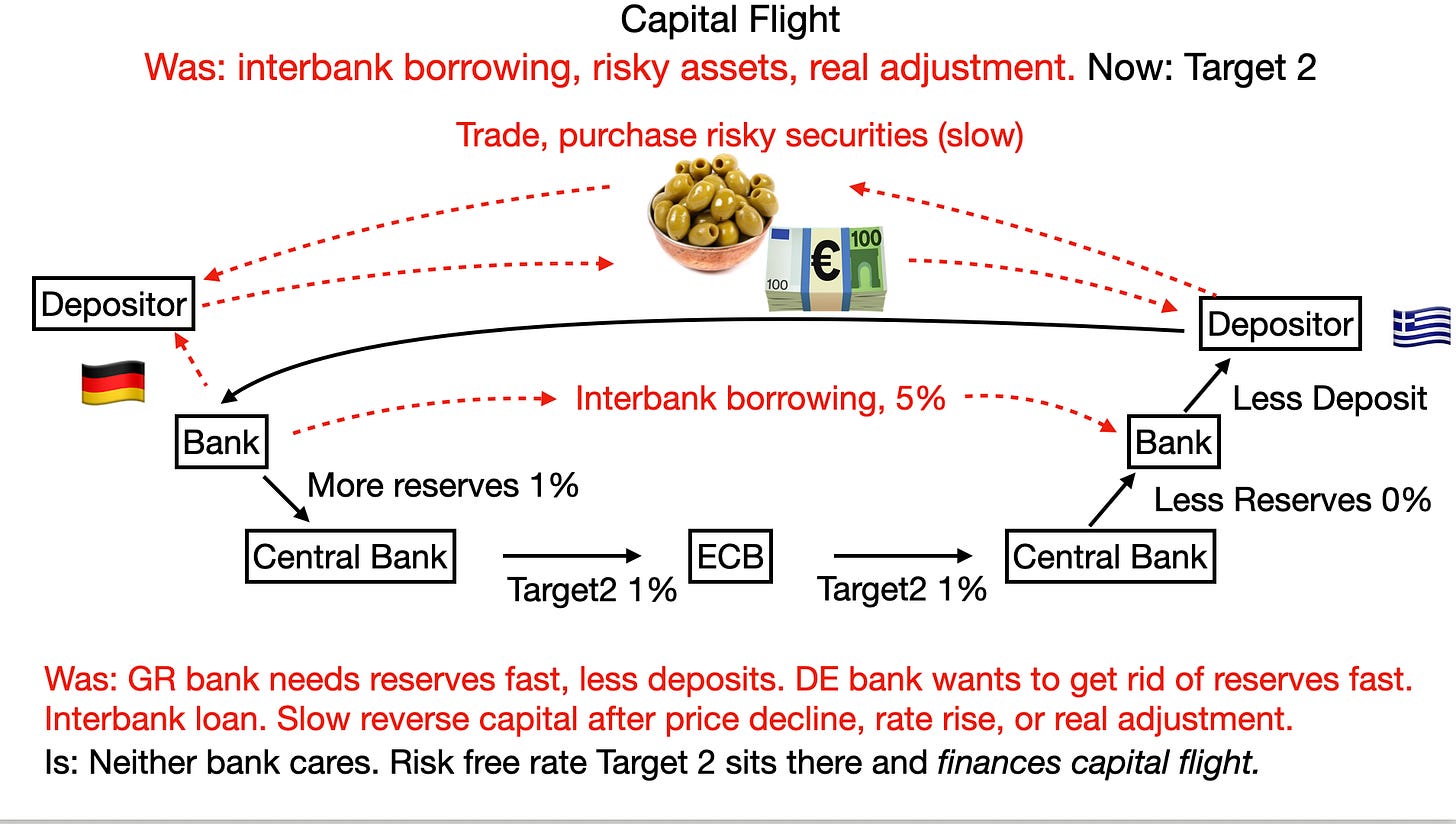

Here is a second example (also source: me). Suppose capital wants to fly from Greece to Germany. Greek bank depositors, smelling trouble, want to take money from Greek banks and put it in German banks. Now, capital and current accounts must add up. If capital wants to leave Greece, some other capital must flow in, or exports must flow out. How does that happen? That capital flight is now financed for long periods of time by the pile up of large long-lasting riskfree-rate Target2 balances.

The depositor asks his bank to send the money to the German bank. The Greek bank asks the Greek central bank to lower its reserve account, “send” the reserves to the German central bank, who will credit the German bank’s reserve account, which then creates a deposit. But reserves are just accounting entries. The German central bank just creates reserves, and a target 2 credit is set up between the central banks via the ECB.

This was, under the initial system, temporary and thus small. For a 100 euro deposit transfer, the Greek bank has lost 100 euros of reserves. But at (say, I don’t know the number) 10% reserve requirement, it still has 900 euros of deposits that need reserves. It needs 90 euros, fast. It borrows those euros on the interbank market. The German bank has 90 euros more reserves than it needs, and they’re not paying interest. It wants to get rid of them, fast. So it lends on the interbank market. 90 euros of capital flight are thus financed by a 90 euro bank to bank loan, and one that pays a pretty high interest rate reflecting the weakness of Greek banks that got the whole business started.

Eventually, macroeconomic adjustments would take place. Germans might find high interest rates or lower asset prices in Greece attractive, and buy Greek securities. Then deposits would flow the other way, undoing the Target2 accounts. Or Greek prices would decline, making exports attractive. Again deposits would flow the other way. “Crisis” management often consists of delaying these adjustments, which is why the Target 2 build up in a crisis.

Now, add the unintended effects of ample reserves and no reserve requirements. The Greek bank is in no hurry to replenish its reserves, and the German bank in no hurry to get rid of its reserves. The target2 just sits there, financing capital flight at the Europe-wide ECB guaranteed risk free rate.

Though less important quantitatively, Target2 also wound up financing persistent trade deficits.

Suppose an Italian wants to buy a Porsche. Again, the capital and current account must add up. Germans must buy Italian securities. Which ones and how? Unwittingly, Target2 ends up the answer for a long period of time.

The Italian purchaser writes a check to the German seller, who deposits it. As before, reserves flow from the purchaser’s bank to the Italian central bank, via Target2 and the ECB to the German central bank, to the purchaser’s bank. Again, with scarce non interest bearing reserves, that would normally quickly be offset by an interbank loan (not directly, but via a few other banks most likely) at higher rate, bringing down the Target2 balance within days. Then, as usual, higher interest rates and lower prices would attract capital or reverse trade flows so that the car was financed by German holdings of Italian bonds, stocks, or wine exports.

Again, with ample reserves, all that hurry is gone, and the imports are financed by Target2 balances for a long time.

Who cares, you might ask? Well, Target2 balances are claims against the whole euro system, so in that sense unnaturally cheap. They are an internal administered rate, not a market rate, and do not reflect the possibility of Italian default or euro exit. If Italy did exit, just what happens to Target2 balances is an open question, but it seems likely that they would be redenomiated to Lira or simply defaulted on. So Target2 financing represents a fiscal transfer.

A third example shows another mechanism, again unwitting. In the early 2010s, desiring stimulus, the ECB wanted banks to lend more. So the ECB added “long term refinancing operations,” and lowered collateral standards, to encourage banks to borrow at the ECB’s very low rates and offer more credit. Which the banks did.

Another little (!) issue at the startup of the euro is that nobody could bring themselves to say out loud that in a currency union without fiscal union, countries must in the end default just like companies do. That was natural at the outset. We’re trying to get together, let’s not talk about such unpleasantness. Plus, it was the late 1990s. Nobody thought advanced country debt crises would be a problem, and debt and deficit rules would surely ensure that the unimaginable remained inconceivable.

Most of all, bank regulation continued to treat sovereign debt as risk free, which it does to this day. So banks could borrow at low risk free rates from the ECB, load up on high yield sovereign debt with no risk weight, and arbitrage the spread.

Now you might say, that’s great, since the banks not the ECB bear the default risk. But the banks are too big to fail, so the risk remains with taxpayers. Banks holding their own country sovereign debt are backed up by the same sovereign that would default. And the ECB made clear that it viewed widespread bank failures after a sovereign failure as an unacceptable “systemic” or “contagion” risk. The banks remain hostages against sovereign default to this day.

“Crisis cycle” tells this story in depth. The euro was remarkably well set up to handle monetary-fiscal separation and to be a common currency without fiscal union. The ECB is an independent central bank, with a single mandate of price stability. It did not originally buy sovereign debts. Fiscal bailouts between countries were ruled out. Debt and deficit limits would make sure countries stayed out of trouble.

But, the founders could not quite say out loud that sovereign debt must be able to default, at the end of some long chain of unfortunate events. There was no resolution mechanism, and as above sovereign debt is treated as risk free for banks. All this is understandable in the negotiation to join a currency union.

Along came violations of the debt and deficit limits, the financial crisis, the sovereign debt crisis, the long zero bound, covid, war, and energy. Each one spurred greater and greater interventions by the ECB, including buying sovereign debt with looser and looser rules.

Now, as the authors point out, the EMU has turned in to another massive fiscal transfer and bank subsidy (and protection) scheme. More worrisome, to us, is the effect on incentives. Clearly, everyone expects that the ECB will not let sovereign spreads rise, let alone let a sovereign restructuring happen. Countries do not hear the message from bond markets that they must borrow, spend, and grow wisely. Banks do not hear the message that sovereign debt must be treated as risky, and diversified and risk managed like risky corporate debt. Financial markets do not channel sovereign debt to holders that can afford to take a loss.

Once you state the problem, reforms are pretty obvious. We do not (much) blame the ECB for crisis interventions. The main problem is that neither the ECB nor the EMU did much to stem these disincentives between crisis. I won’t wander even further off topic now however. (I owe everyone a summary of “Crisis Cycle!” Another day.)

PS, the rest of the conference was great. I particularly liked the novel “Global Hegemony and Exorbitant Privilege” by Carolin Pflueger and Pierre Yared, part of the new geo-economics or security-macro papers. Military strength begets low interest costs on debt, and vice versa, with interesting transitions between low interest rate global power and not. Also Phillip Schnabl’s “Banking on Deposits” keynote. And… well, the whole thing was good.

Seems to me that even readers with more than average understanding of economics will find this essay difficult to follow.

Suggestion: write a primer to the article.

The outlined ECB operations are no mystery (including the fact that QE was essentially hidden government financing with high spreads for banks as intermediaries) EXCEPT for Target2. The latter is a simple cash management system within the Euro area. Like any such system, it balances credits and debits of national central banks: some have cash, others owe it. There is no requirement to settle positive/negative balances (under the Fed structure, my understanding is that balances must be settled once a year). In early 2011, a retired Bundesbank Director studied the Annual Report of the Bundesbank and noticed that there were unidentified assets of about €300B. He asked the renowned German economist Hans-Werner Sinn what these assets might be. And Sinn subsequently revealed to the world the magic of Target2: a system where money can flow to surplus countries without the deficit countries needing to have the cash. Deficits automatically increase the claims of the surplus country. Here is a ficticious story to make the point: at the peak of the Greek crisis, a wealthy Greek met a German banker at the beach. The Greek said: "I want to transfer the €50M which I have with a Greek bank to your bank in Germany. My Greek bank tells that they can only do that if you lend them the €50M. Could you do that?" The German banker asks: "How stupid do you think I am?" Instead, the Greek simply gives his Greek bank transfer instructions for the €50M and the money flows to the German bank. No sweat. Why? Because the Bundesbank's Target2 claims against the Bank of Greece increased automatically by €50M. End of story. When stand-alone countries run out of foreign currency, they have to stop importing. When Greece went bankrupt, imports and the current account continued to run enormous deficits facilitated by Target2. Today, the Bundesbank has about €1.1TR claims against other central banks. The largest takers are Italy and Spain with well over €400B each. Followed by France and Greece with well over €100B. They are not loans or debt, they are clearing balances within the Euro system. As long as the Eurosystem survives, they don't really matter. Should the Eurosystem collapse, there is a good chance that they become hot air. This article is old but still valid: https://klauskastner.blogspot.com/2018/03/target2-claims-revisited.html