Change, demographic and intellectual

I saw two very nice papers this week, that blog readers would enjoy

“The Wealth of Working Nations” by Jesus Fernandez-Villaverde, Gustavo Ventura, and Wen Yao has a simple and lovely point. It’s best encapsulated (as Jesus did in a great seminar presentation, which should be up here early Feb) with the argument over Japan. Japan’s GDP growth stagnated around 1990. “Secular stagnation” cry its critics and point to the central bank. Wait a minute. Growth per capita didn’t stagnate as much. Japan’s population growth slowed down. And growth per working age person is the same in Japan as in the US!

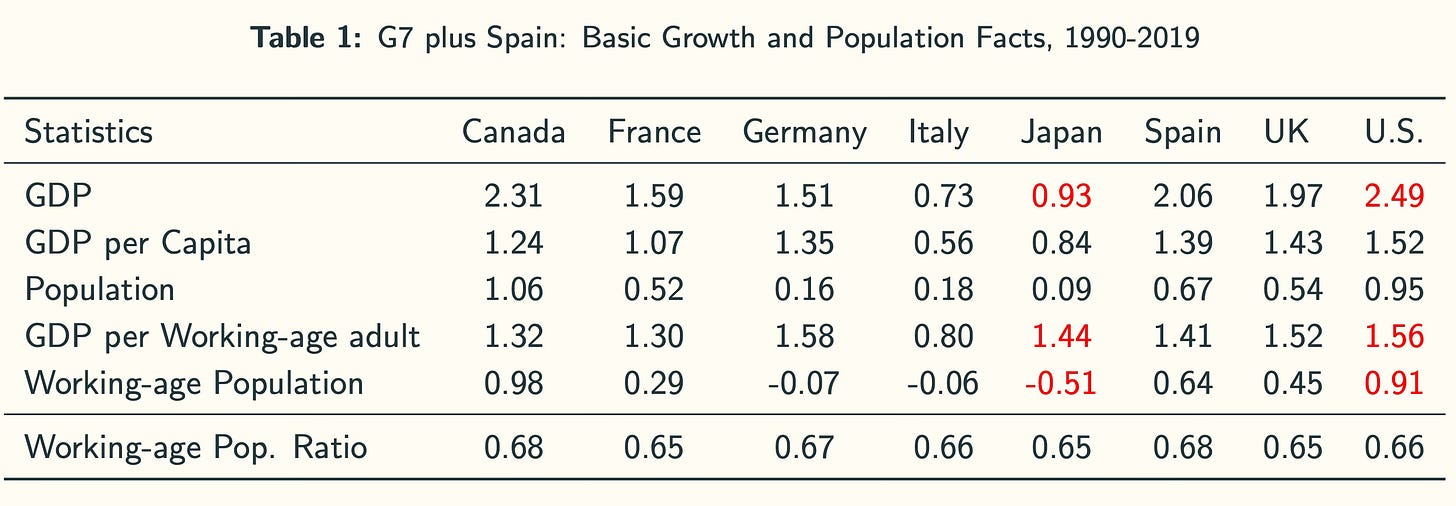

Here is the basic point in a table:

Top right, the US grew 2.49%, and Japan 0.93% per year. But GDP per capita is 1.52%, and 0.84%, closer. Most of all, Japan has many fewer young people. Growth in GDP per 15-64 year old is 1.56% in the US and 1.44% in Japan, nearly the same. Most of the G7 are just about the same on this measure, with the tragic exception of Italy.

Not all is the same. This is just growth. The level of GDP per working age adult varies across these countries. The somewhat puzzling lack of convergence remains.

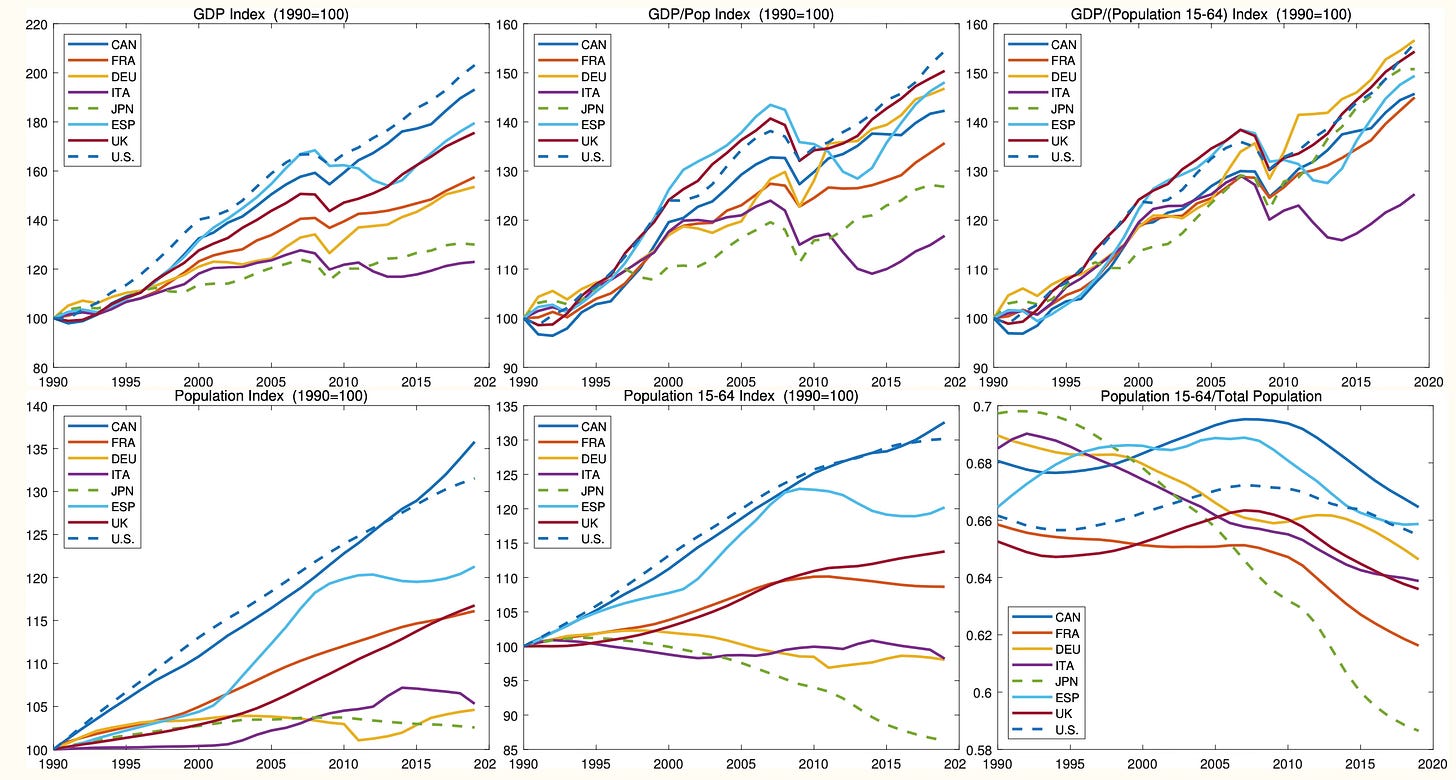

Here is the same point in pictures. Top left, normalizing all countries to 100 in 1990, GDP fans out, with US near the top and Japan and Italy near the bottom. Top middle, GDP per capita fans out less; US population grew more. Top right, GDP per working age adult is almost the same across US and Japan, though tragically low in Italy. The bottom row shows the population trends behind these divisors. Note everyone’s ratio of working age to total population peaked in 2010 and is headed downward. Japan just leads the trend, having peaked in 1990.

The “right” number depends on what question you want to ask, what version of “how well is an economy doing?” If you want to know how many aircraft carriers a country can build, or if the government can repay its debts, you want GDP. If you want to measure labor productivity, the fundamental efficiency of its businesses, you want GDP per hour. (Jesus brought up a very important limitation there: Europe has had more restrictive labor laws and more low skill people just not working. That fact boosts average productivity. The US seems to be “catching up” in this regard.) If you want to measure overall average standard of living, GDP per person is a good beginning. GDP per working-age person is a measure of productivity that includes all the impediments from high taxes to regulations that discourage people working. It leaves out fertility, a country’s crucial ability to produce workers to pay for everyone else. That is an important issue, but it is at least a very long run issue, and not one on which we have well understood policies.

Rather than answer a specific policy question, I regard this as an interesting decomposition. Of a country’s GDP growth, how much comes from more people, and how much from more working age people, how much from more of those people working, and how much from the efficiency of those who do work?

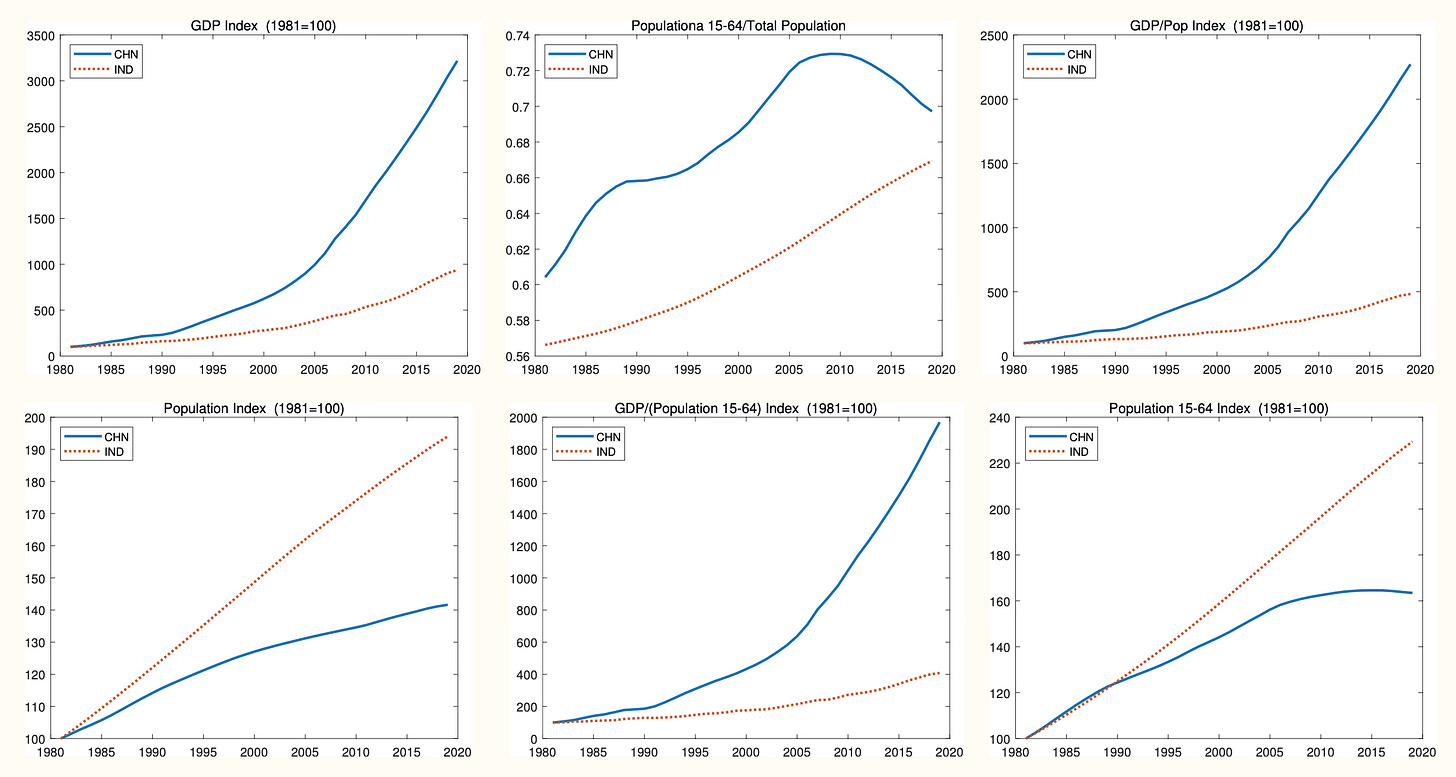

India vs. China is interesting. Top left, China grew (from a very low base) spectacularly. Top middle, China’s population is trending down. But none of these adjustments explains the divergence between China and India. India is still underperforming.

Longer trends

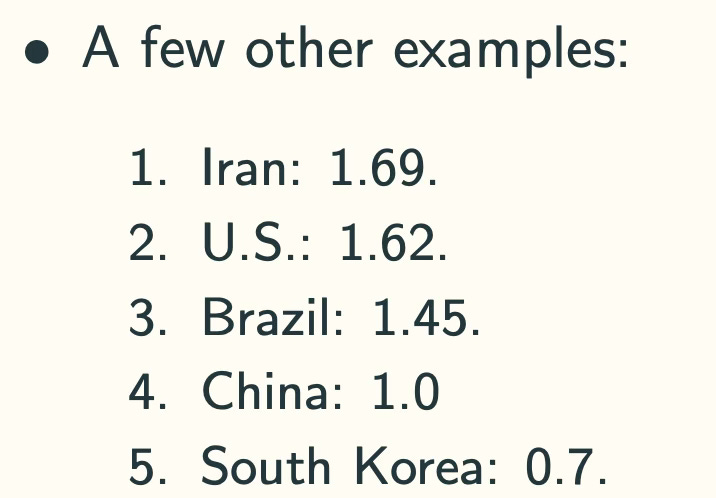

Jesus closed with a more general discussion of population trends, which is one of those huge elephants in the room, inexorably rising tides, asteroids on collision course, choose your metaphor that we all sort of know about and all sort of ignore. Fertility is crashing around the world. Some replacement rates:

Remember 2.1 is replacement in advanced countries, though in poorer countries it can be closer to 3. South Korea’s population will be cut in half in a generation. The “demographic transition” to very low birth rates seems universal. And thus basically immune to the standard sorts of policy bandaids. Women didn’t have lots of children in the 1950s because there was ample government-provided day care. Japan and South Korea are simply a little bit ahead of the rest of us. Jesus went through the evidence, concluding that standard demographic estimates are far too optimistic. They typically forecast a “rebound” in fertility, though for no good reason.

Looming population decline, and a sharply different age profile as we work through those dynamics, are just a fact, though often wrapped (as any change) in crisis mode. Does the level of population matter for economic growth? We’re about to find out the answer to this central question of endogenous growth theory. My sense is that climate forecasts, which worry about 5% of GDP in 100 years, by and large use standard and thus likely too high population forecasts. De-population and de-growthers are likely to have their dreams come true. Of course pay as you go pensions and overlapping generations models in which government debt is a free lunch will be in trouble.

*******

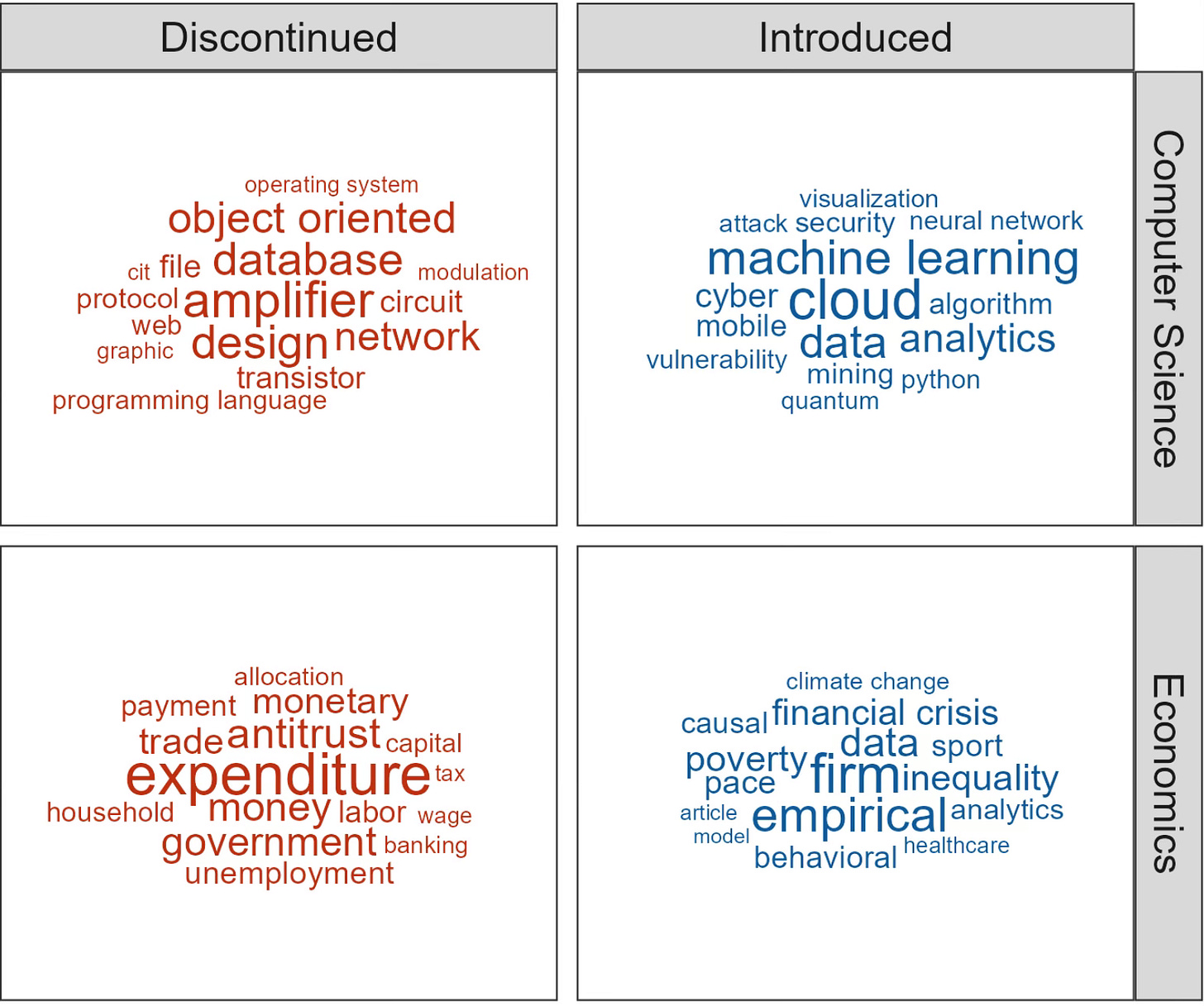

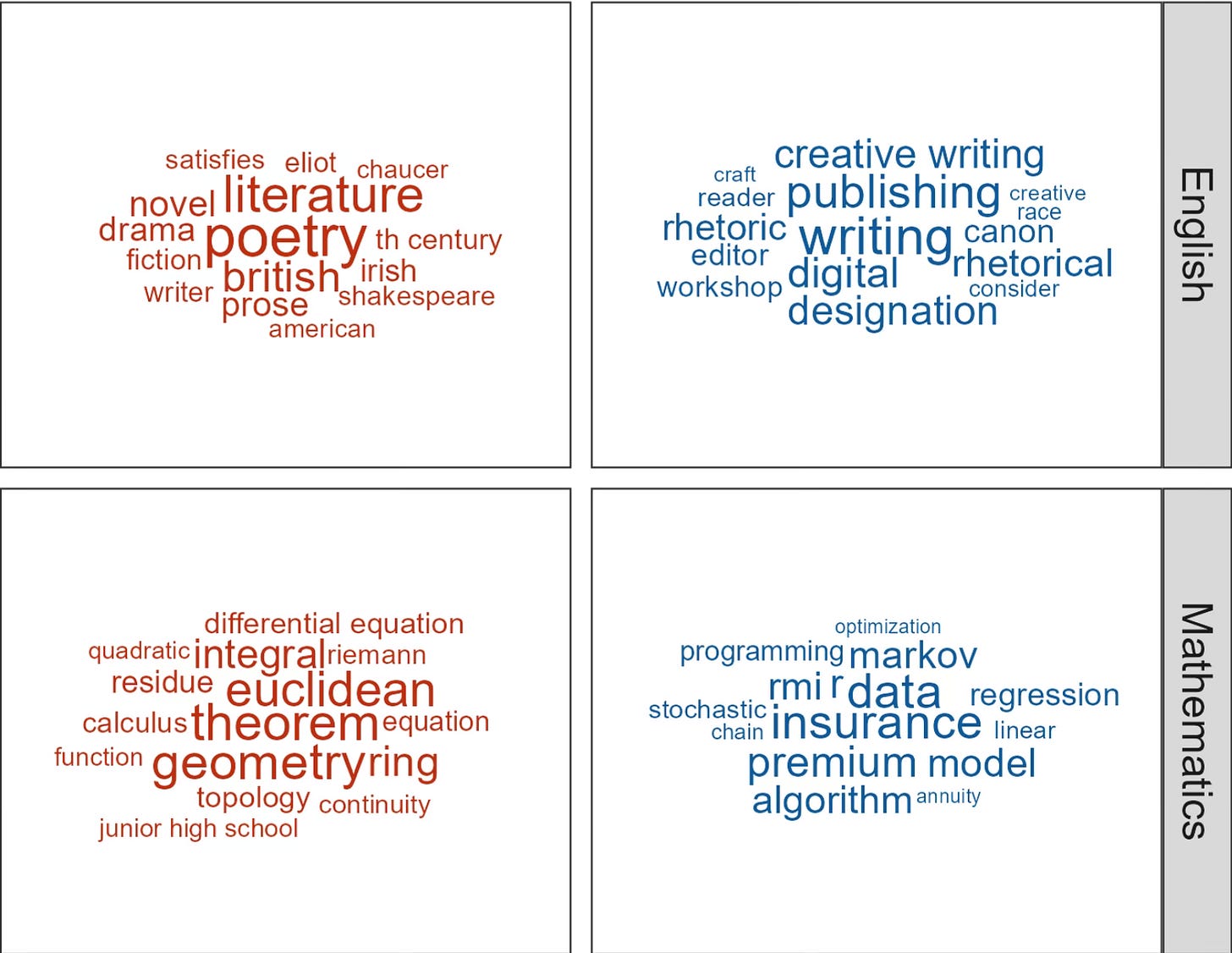

This is a word cloud from course descriptions of discontinued university classes vs. new university classes. It’s from “Student Demand and the Supply of College Courses” by Jacob Light, a PhD job candidate from Stanford. Jacob’s paper is about how college courses are, and often are not, changing over time. You won’t be surprised one pattern is that professors hang on to teaching the same old things even as enrollments decline. Jacob offers some more gentle interpretations of that phenomenon however.

I found this interesting as I mostly find myself in the camp of the fuddy-duddies across all these fields, and I put up the clouds in case you do too. I can’t help but note that macro — “monetary,” “payment,” “trade,” “capital”, “money,” “unemployment” “banking” — seems to be on the way out. The sample ends before the pandemic recession and subsequent inflation though, so maybe there is some hope for us! I have to ruefully admit that “climate change,” “poverty,” “inequality,” “behavioral,” and above all “empirical” are the big new concerns, as you also see in ASSA sessions, articles, and so on. But maybe what gets written about inequality and climate will change

Computer science changing from “database” “design” “programming language” “web” and “circuit” to “machine learning” “cloud” “data analytics” and “quantum” seems to reflect the times as well. I wonder if old school computer scientists are grumpy.

No surprise that English literature has moved from, well, “literature,” such as “Chaucer,” “Eliot,” “Shakespeare” “poetry” in the “th century” to the perhaps more job oriented “writing,” “publishing,” “editor,” “craft,” but also “race,” “designation” (?). The lack of social-justice verbiage here is interesting, but Jacob has a whole section on that. The sample is a large one, not just the elite ivies.

It’s interesting that math as well as CS and English seems to be moving to more “practical” courses. I still think of “differential eqution,” “integral” “residue,” “euclidean,” “theorem” (“theorem” is on the way out in math classes!), “geometry” and so forth as pretty central math. I guess now “programming”, and “algorithm” take its place. (though that sounds like the courses CS got rid of!) “Markov” “data” “stochastic” and “regression” are all wonderful, but that’s statistics and econometrics. Jacob didn’t mention it, but moving in to other fields is a natural response when fields don’t expand quickly enough.

The big question is cause and effect. Are changes led by employer demands, student demands, or faculty demands? Are the latter from changes in the composition of students or faculty or changes in the tastes of existing ones? The paper has a nice instrumental variables estimate of that question, but I’ll leave it here as one to ponder.

Writing/grammar note/question:

This sentence: "Women didn’t have lots of children in the 1950s because there was ample government-provided day care" could be interpreted multiple ways, so I find it a bit confusing.

I think it's supposed to be sort of a sarcastic jab? I.e., "Look, there wasn't government childcare in the 50s and yet women still had lots of kids." But it's also possible to just read it straight: if you don't know the data well then you might interpret that as saying "the fact that there was ample childcare in the 50s led women to have lots of kids." But that, of course, doesn't really make sense!

Maybe I'm being pedantic. But could you rephrase to include a little nod. Like: "It's not like the lack of ample government funded healthcare in the 1950s prevented women from having lots of kids."

-->"South Korea’s population will be cut in half in a generation."

I wonder if that's quite right. (I might not understand the fertility statistic.) Wouldn't it be that the new generation born will be one-third (0.7 divided by 2.1) the adult generation having babies. Since the live population is made up of 3-4 generations, depending on the measure of a generation used... It would take two generations to cut the population in half. Dire still, I suppose, but playing out over two generations allows for a lot of things to happen. (I don't know the time it took S. Korea to go from 2.1 to 0.7.)