Brazilian Inflation and Disinflation

Last week I read a nice capsule history of Brazilian inflation, by Pedro Carvalho. Pedro is a Stanford graduate, and I helped as adviser on the project. This builds on and complements the Brazil chapter by Joao Ayres, Marcio Garcia, Diogo Guillen, and Patrick Kehoe in the excellent Monetary and Fiscal History of Latin America.

Who cares? We do. As we head to our own monetary-fiscal collision, the experience of other countries around the world is going to be a lot more useful than trying to squeak just a tiny bit more information out of the 1001th VAR run on benign US data. Of course these are also lovely fiscal theory of the price level episodes.

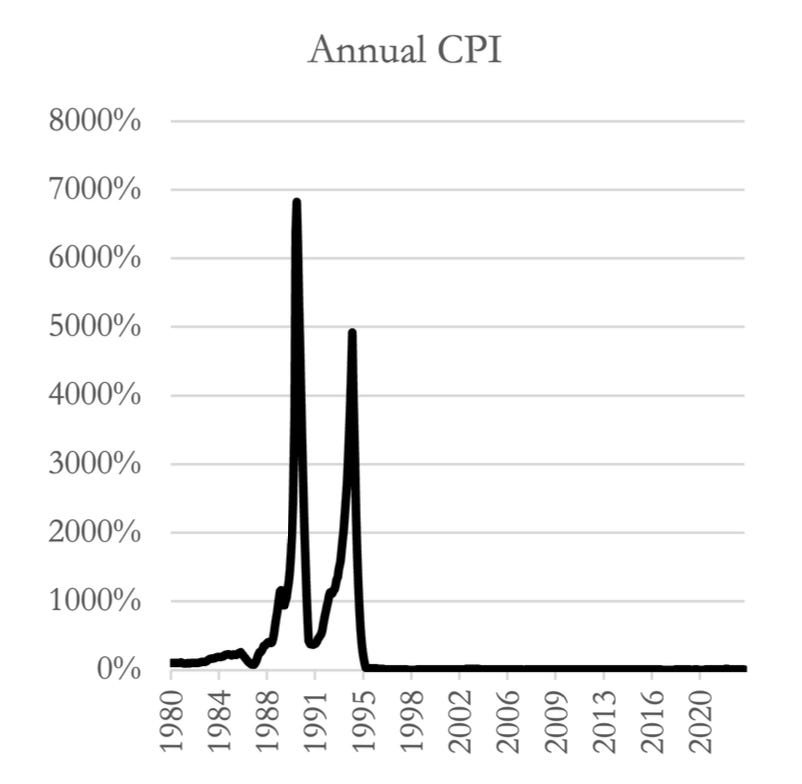

From 1947 to 1986, Brazil had chronic high (50%) inflation, with occasional higher surges. Starting 1986, “after the end of the military rule, .. the new democratically elected government introduced the first of what would become a series of six stabilization plans to fight inflation.” Beware selection bias. Failed stabilizations are as interesting as successful ones.

The first few plans of this series targeted inflation inertia instead of inflation expectations. They temporarily froze prices and exchange rates, prohibited wage indexing, or would introduce new currencies that cut three zeros from the former. All five plans before the 1994 Plano Real failed: inflation shot back up a few months later.

We forget the prevalence and power of old macroeconomic ideas. Lots of economists thought that inflation was all about wage-price spirals, indexing, inertia, self-fulfilling expectations, price-setting rules and more. Many still do. Today’s conventional policy framework either has no “nominal anchor,” or buries it in footnotes, viewing inflation as just the collection of price increases. We may not know what’s right, but failures teach us a lot about what’s wrong, and what not to repeat.

The early stabilization attempts also failed to address forward looking inflation expectations through credible reforms. None of the plans prior to the Plano Real implemented meaningful fiscal reforms.

Another persistent habit is to regard policy as a sequence of actions — interest rates up or down, taxes up or down this year — rather than regimes and institutions, by which people plan for what the future will bring.

By 1993 Brazil was experiencing a full blown hyperinflation. Then came the 1994 Plano Real, as classic an end of hyperinflation as one can ask for.

The plan included another interesting round of monetary reforms. The government instituted a parallel unit of account, the URV (unit of real value), and pegged to the dollar. “Prices were listed in both URVs and Cruzeiros Reais, but transactions still occurred in Cruzeiros Reais. A few months later, “the URV was replaced by the new currency, the Real, which initially had a crawling peg to the Dollar.” The idea was to try to break expectations without price controls. “The central bank gained more autonomy.” The National Monetary Council “was reduced to only three key members: the central bank governor, the finance minister, and the planning minister” Well, not complete autonomy. The central bank increased reserve requirements — monetarist thinking was included.

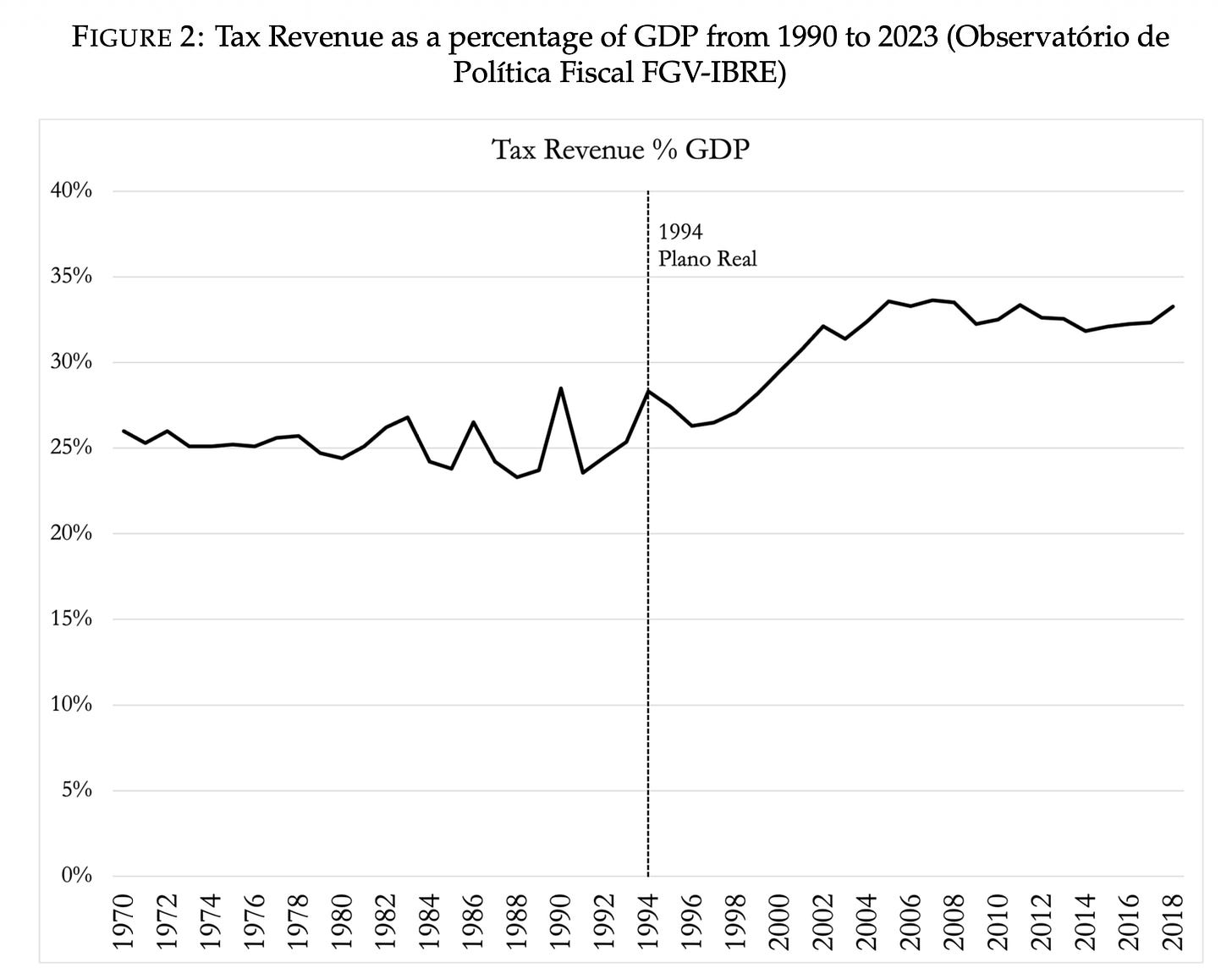

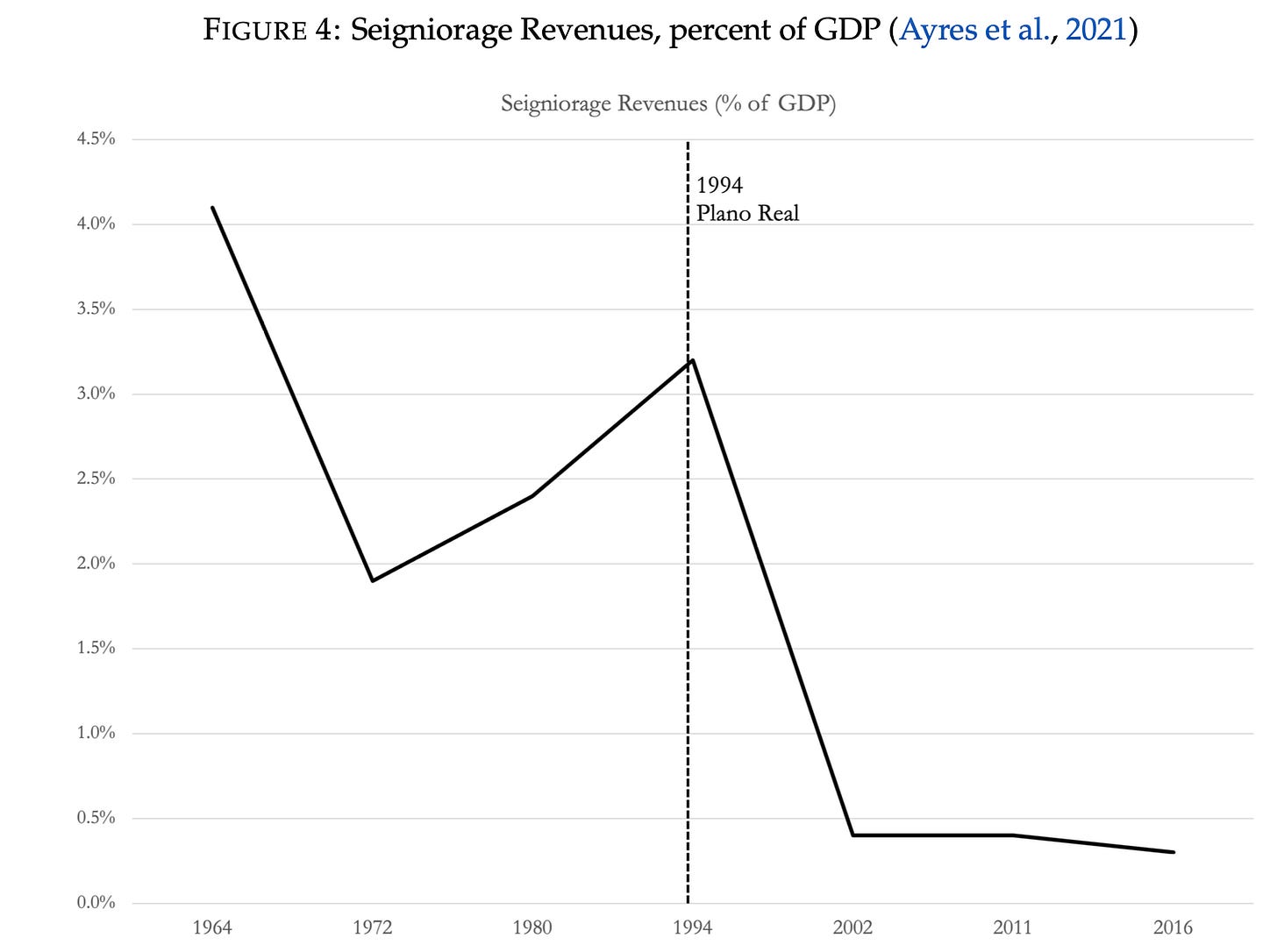

But the real novelty relative to the previous reforms was fiscal. “In 1993, in preparation for the Plano Real, the government introduced new taxes to prevent a fiscal imbalance when seigniorage revenues fell the following year.” The taxes worked, providing a permanent increase in revenue from about 25% to 32% or so of GDP. This is a very large increase. A credible fiscal situation and agreements under the Bradly plan reopened access to international capital markets. As in other circumstances, credibility in paying it back allows governments to borrow more, even right after hyperinflation. “…the government also started announcing fiscal targets and enacted the fiscal responsibility law, imposing more constraints on spending that ensured the surpluses that Brazil saw in the early 2000s.” Confidence in expected future surpluses, in a change of regime not temporary and reversible austerity is, in fiscal theory eyes, the key to stopping inflation. “Finally, after 1994, the government continued to promote microeconomic reforms such as privatizing state-owned enterprises and bank reform.” Microeconomic reform lets the economy grow faster, which is good for the long-run budget.

It worked, as you see above. “Inflation dropped dramatically, from 4,005% in July 1994 to 27% the following year, and hyperinflation did not return.”

My maxim: The end of a serious inflation almost always comes with the combination of monetary, fiscal, and microeconomic reform.

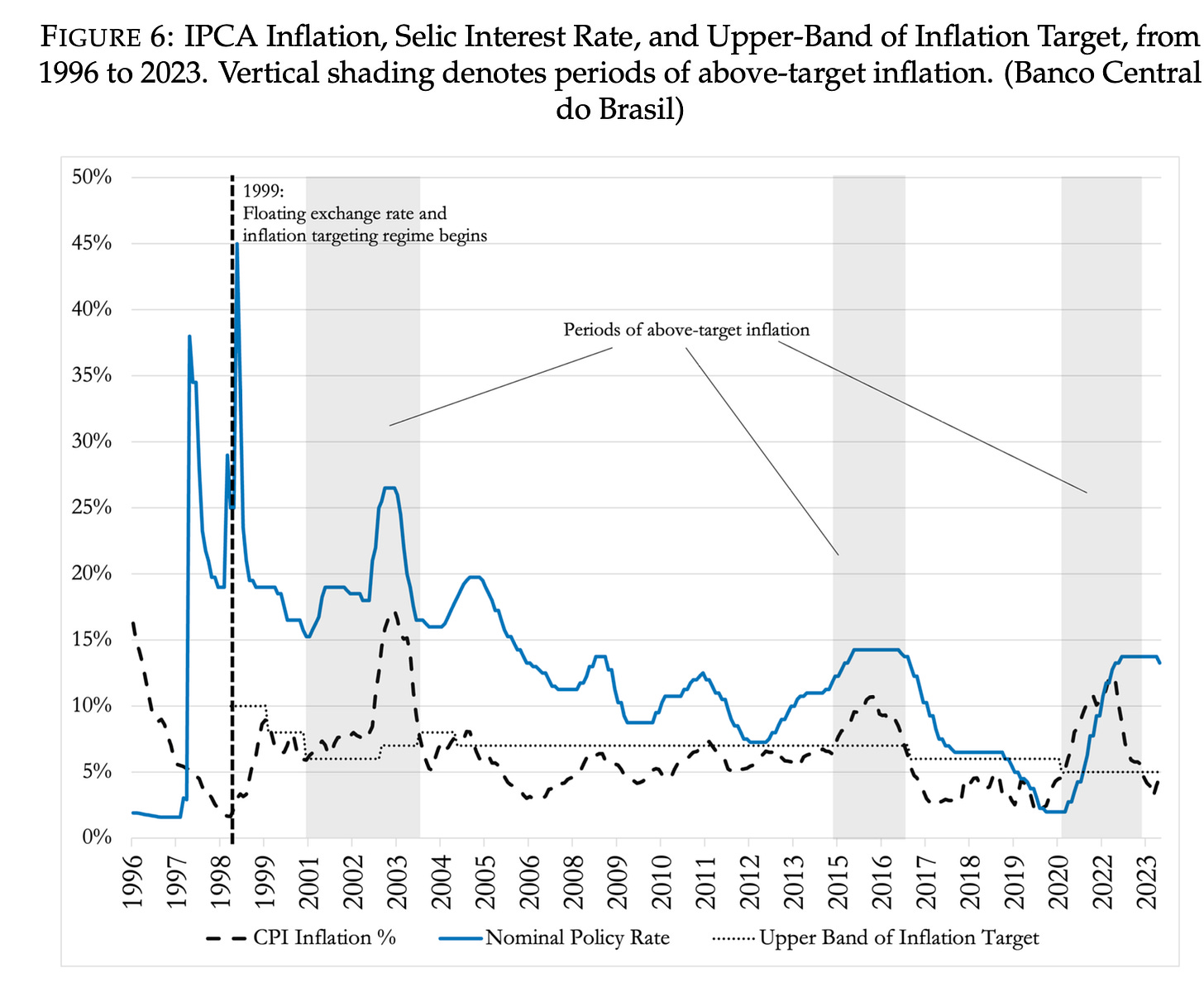

Alas it did not stick forever. In the 2000s, Brazil saw three waves of over 10% inflation. More stories for us.

Prior to the 2002-2003 inflation, there were no significant deviations in monetary aggregates or fiscal spending. However, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (Lula), who was then a presidential candidate, rose in the presidential polls and won the elections. He had advocated for national debt renegotiation and even default in the past and his rise caused a change in expectations of future fiscal policy. It is widely agreed that the 2002 inflation was driven by uncertainty over the continuity of the macroeconomic reforms implemented by the Plano Real (Ayres et al., 2021). Fear of a default led to a significant devaluation of the exchange rate (passing through as higher import prices) and an increase in interest rates on government debt. Inflation expectations recorded by the Central BankFOCUS survey unanchored from the target rate in October, between the first and second rounds of the election.

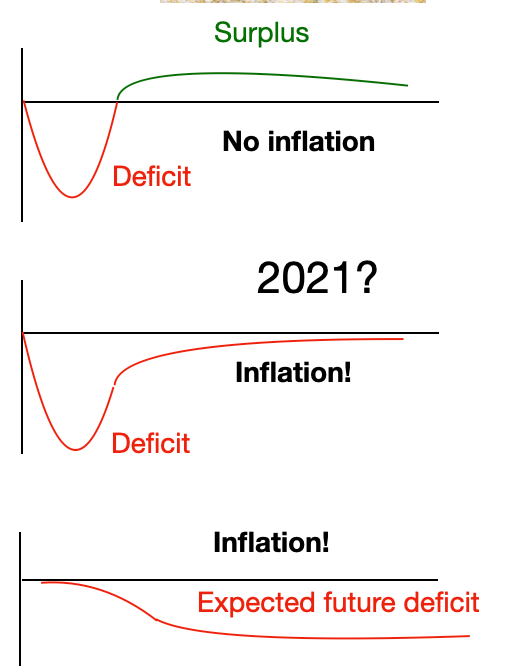

As I explain fiscal theory, it points to several scenarios.

A deficit that people expect to be repaid causes no inflation. A deficit that people do not expect to be repaid causes inflation. And a loss of faith with no current deficit can cause inflation. Lula seems like a good story for the latter. (The fourth possibility, not graphed, a rise in the real interest cost on government debt, that the government cannot or will not pay for with increased surpluses, causes inflation.)

Even “Blanchard (2004) concluded that Brazil experienced fiscal dominance during this period…”

However, not all populist leftists govern that way, at least all the time:

Once elected, however, Lula bowed to markets by committing to maintain the Plano Real era macroeconomic policies — and kept his promise. The central bank raised rates, and inflation slowed by the end of 2002. During his administration, the government recorded fiscal surpluses, GDP per capita grew under the tailwinds of a global boom in commodity prices, Brazil accumulated foreign reserves, and external public debt fell (Ayres et al., 2021).

Monetary policy clearly did not start the 2002 inflation. But what role did it take in ending the inflation? Rates did rise, but as I look hard at the plot, rates rose less than the magic one for one needed in standard theory for rates to bring inflation down. Rates rose even about one for one in the US in the 1970s. Also there was no 1980-82 US style recession to bring down inflation through the Phillips curve. My fist guess is that restored fiscal and growth credibility did the trick on its own, and the central bank did no more than keep the real rate about constant, and perhaps signal that it would not monetize debt should things get out of control again.

The merry go round continued.

After Lula’s re-election in 2006, policy shifted to more extensive state intervention.. These policies expanded deficits…“creative accounting” made measures of fiscal deficits even more difficult to estimate… and eroded the fiscal credibility achieved in the late 1990s after the Plano Real reforms (Ayres et al., 2021).

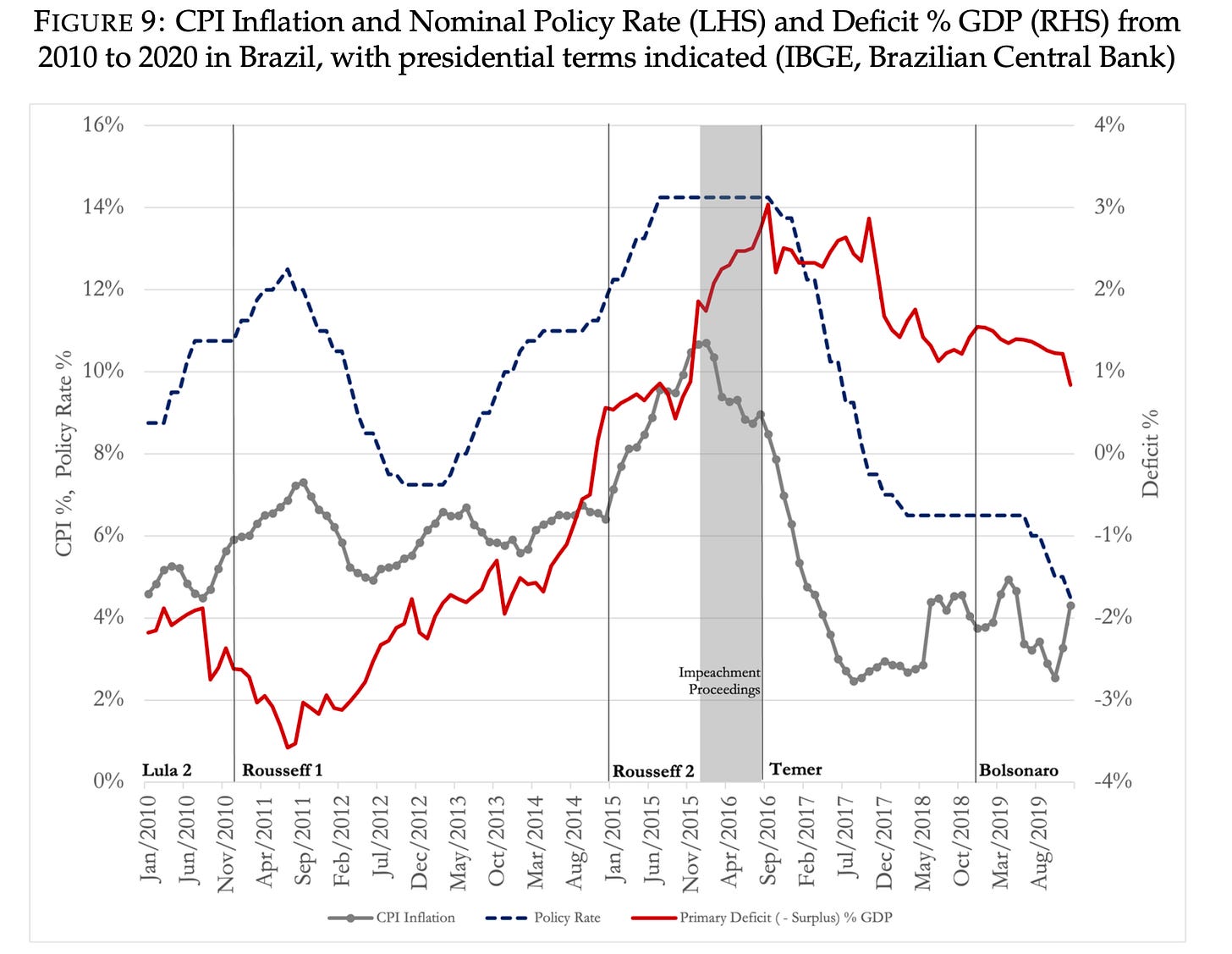

In the mid-2010s, Brazil experienced another period of double-digit inflation under President Dilma Rousseff, followed by disinflation and stringent fiscal measures implemented by her successor, President Michel Temer. There were no significant changes to monetary policy rules between the two administrations, but there was a radical shift in fiscal policy.

Under the Rousseff administration (2011-2016), government expenditures continued to increase with the expansion of social welfare programs, while at the same time, no significant tax or microeconomic reforms were enacted. ..

The budget steadily deteriorated, moving to deficit in 2014. Inflation peaked in July 2016.

Rousseff was impeached from office in mid-2016 due to an infringement of the fiscal responsibility law (enacted in the Plano Real period) linked to the so-called “creative accounting” tactics…Her successor, Temer (2016-2018), implemented landmark legislation to restore fiscal discipline later that year. This was in the form of a constitutional cap, formally enacted late in 2016, that limited the annual growth of federal spending to the previous year’s inflation rate, effectively freezing real government spending for up to two decades.

If Brazil can do it maybe we could think about it? Maybe after a few more bouts of inflation we will.

Brazilian Central Bank governor Campos Neto cites the series of 2017 fiscal and microeconomic labor reforms as policies that allowed the central bank to cut rates, as well as to lower its neutral rate target (Figure 5) (Campos Neto, 2023). Even before the reforms were approved, during the impeachment proceedings and provisional government period, there was clear political will and momentum which explains why expectations started to change in 2016. Figure 9 shows how inflation, the central bank policy rate and the real primary deficit evolved during this period. Vertical shading indicates the period of transition between the opening of impeachment proceedings against Rousseff, through Temer’s provisional government, and his inauguration. Notice how the policy rate responds to inflation throughout the entire period, and the main variation is in fact in the deficit figure.

The upward trend in deficit breaks, but the actual deficit does not move dramatically toward surplus in this picture. The disinflation seems to follow the script: disinflation happens on change of regime, in anticipation of policies, not necessarily when the policies actually happen, if the change is believable.

I run in to a lot of doubt about rational expectations, and ordinary people understanding events. Brazilians seem perfectly capable of it.

When a country has 6 stabilization plans less than 40 years, you have don’t have a plan; you a fiscal mess

I'm Brazilian. A similar process occurred around the last election (2021): Bolsonaro implemented a fiscal expansion, and after Lula was elected, they revised Temer’s fiscal rule to increase the federal government's fiscal capacity. We saw inflation above target in each of the last three years, and in 2025, it's projected to be right at the top of the target range.