Are bonds hedges or risky opportunities?

(I wrote this essay for a talk at the Fiduciary Investors Symposium at Stanford Thursday September 19 2024. You can find a pdf version on my website here.)

1 Introduction

Are bonds great hedges? Or perhaps risky securities that nonetheless offer good returns after compensation for that risk?

I was asked to speak about the bond-stock correlation, which obviously bears on that question. When bond returns correlate negatively with stock returns, then bond returns are a good hedge for stock market risk, and one might want to hold them as a sort of insurance despite poor average returns. When, bond returns correlate positively with stock returns, bonds had better offer a good prospective return to make up for that addition to risk.

In the usual way to think about this question, we compare returns of any security with beta times the market return, and then chase the ephemeral alpha. These quantities all change over time, so we then descend to statistical models of time-varying means and time-varying condi- tional covariances of returns. (Campbell, Pflueger, and Viceira, 2020 is the state of the art in this style.)

Posing the question this way makes a bunch of implausible implicit assumptions. The framework only applies for an investor who currently holds the market portfolio, and cares only about the one period mean and variance of that portfolio’s return. Investment should be based instead on correlation (beta) of a security’s return with that of your portfolio. Do you have assets such as a business, a job, or real estate? Are you a pension fund or endowment with a liability stream to fund? Then betas with respect to the market portfolio are not relevant. Do you care about lifetime income, a lifetime stream of payments, not just about the mean and variance of the next reporting period’s mark to market wealth? Then the framework does not apply to you. That distinction is particularly true for bonds. Bonds lose value when subsequent yields rise, and then make up the loss. If you’re going to hold bonds to maturity, you don’t care about the temporary loss in value.

Posing the question this way this also ignores a central fact of life: for every buyer there is a seller. The average investor holds the market portfolio. We can’t all be smarter than average. For everyone to whom we tell to buy, there must be someone who we tell to sell. Bonds may be a great hedge, but everyone else knows that. Have they already bid up the price so much that the hedge is not worth it, to you? Indeed, should you be selling, rather than buying insurance? (For more on the implications of this simple fact, see Cochrane, 2021, 2011.)

I offer a different approach. Rather than a complex statistical model of time-varying corre- lations, let’s look instead at times when bonds did well or poorly. Let us understand events that make bonds hedges or risks. Then we can think about whether we need hedges for those events, or if we’d rather sell hedges to others and take on the risk.

2 Financial crisis

The 2008 financial crisis is a classic example of an event in which long-term US treasurys were a great hedge, worth holding despite low expected returns.

Figure 1: The macroeconomic situation. Unemployment and the CPI. Gray areas are the recession. The vertical line is October 1 2008.

Figure 1 reminds of the macroeconomic situation. A recession started in mid 2008. When the financial crisis exploded in October 2008, the economy plunged. Inflation fell, meaning that bonds paid off in more valuable dollars than expected. Inflation is measured as growth from a year earlier. The price level plunges quickly, and inflation only shows that plunge with a lag. The real value of bonds rose because bond prices rose and also because the value of dollars rose.

Figure 2: Yields. Gray areas are the recession. The vertical line is October 1 2008.

Figure 2 plots bond yields in this episode. The credit spread widened dramatically. BAA and AAA bond yields spiked upward, meaning that their prices tanked. Short term interest rates fell, as the Fed promptly lowered them to zero. Long term treasury rates fell, meaning their prices rose.

This was a classic “flight to quality,” in which investors tried to sell credit risk and move to treasurys. The Fed tried to supply more treasuries and reserves, and to buy or subsidize the buying of risky securities, but could not allow everyone to sell out who wanted to so so, so prices rose.

Figure 3: Cumulative log real returns on 30 year, 1 year and 30 day treasurys and the S&P500 index. Gray areas are the recession. The vertical line is October 1 2008. Data source: CRSP.

With this background, Figure 3 presents the cumulative real return on the S&P500, on 30 day and 1 year treasury bills, and on 30 year treasury bonds.

The S&P500 lost 75% of its real value (in continuously compounded or log terms), a stunning fall. (The index fell from 1594 in Oct 2007 to 735 in February 2009, a 54% decline or log(735/1594) = -0.77 decline. The total real return adds dividends but subtracts inflation.)

Cumulative short term bond returns did not rise much. Short term bonds are hurt, not helped, by the fall in interest rates, seen by the dip in real return just before October 2008. The real returns rise in early 2009, as inflation falls during the recession. So they are a small hedge, but largely provide just a real riskfree asset through the episode.

The small fall in 30 year bond yield, together with the decline in inflation, shows up here as a large positive return on 30 year bonds coincident with the stock market collapse, and the collapse in risky bond prices. In this event, 30 year treasurys were a great hedge against stock market and risky credit! Here is a dramatic negative stock-bond correlation.

You can also see negative stock and bond correlation in the year before and the years after the crisis. However, the crisis matters much more. Fall 2008 was a genuine financial crisis. Anything with a whiff of credit risk was falling in price. Many trading strategies such as momentum and carry trade suddenly had their once a century floods. It was nearly impossible to borrow. Standard collateral was unacceptable. Literal arbitrage opportunities opened up, because not enough traders could borrow the money needed to close them. Many large investors, such as university endowments, were trying to sell large portfolios in a panic, and were unable to roll over debt. More generally, standard finance focuses on monthly or weekly correlations. But what really matters is how assets behave in the big times of stress. The standard simple theories (CAPM, iid returns) make assumptions under which daily, weekly, or monthly correlations ac- curately measure how assets behave under times of big stress. But those assumptions are wrong (more below). For now, just ignore high-frequency correlations unless you’re a high frequency trader, and let’s focus on the big events.

The fundamental determinant of risk in finance is not the market portfolio, but the hunger for cash, the marginal utility of cash in technical parlance. The marginal utility of cash in December 2008 was huge, extending beyond what is reflected in a calamitous market return. The later stock market rises and falls were not correlated with all these other events.

So, should we go out and buy lots of 30 year bonds? Not quite so fast. Other investors know about this behavior and have already bid up the price. 30 year bonds have a lower long-run average real return compared to stocks. More importantly, as you can see in the graph, even AAA corporate debt has about a 1% yield premium over 30 year bonds and BAA debt about a 2% premium. This premium is a lot larger than the default probability of a AAA corporate and substantially above the BAA default rate as well. You can make a lot more money holding BAA and AAA bonds over long periods of time. To get insurance, you have to pay a premium! So the question is, whether the “negative beta” of 30 year treasuries in the financial crisis is worth, to you, losing a substantial average return.

Moreover, the crisis turned out to be temporary. Even the Great Depression turned out to be temporary, though you had to wait for the end of WWII before stocks recovered. If you could hold stocks, AAA, BAA, or many other risky securities through the crisis and into the recovery, you came out fine. Stocks, it turned out, were like bonds: When prices of default-free bonds fall, yields rise, so an investor holding to maturity doesn’t really care about mark-to-market losses along the way. When the stock price went down, the expected return apparently went up. A financial crisis is by its nature temporary. Eventually the financial arteries unclog, and business returns to usual. The issue is, who can bear risk in the meantime.

The catastrophe of the financial crisis was only a catastrophe for people who really needed cash in the middle of the crisis; people who had to sell assets, roll over debt, cover for vanishing collateral, and so forth. Thus the value of long-term bonds as a hedge really only mattered for those people. If you are a long-only long-term investor, who doesn’t really need unplanned infusions of cash, stocks and risky bond price falls were really not a concern to you. Therefore, the fact that long-term bonds had a temporary mark to market price rise as stocks and risky debt had a temporary mark-to-market price fall really is of no benefit to you, and not worth suffering a lower mean return to obtain.

I’m overstating here. Nobody knew for sure that the fall in prices would be temporary. I remember talking to an adviser to a large endowment, which despite its professed status as a long-term investor that ignored market downturns, was selling in a panic. Why, I asked? I got two answers. First, the institution needed to roll over short term debt, and its credit rating had fallen. It needed cash fast. Second, the adviser said, roughly, “we don’t know for sure when or if this will turn around. It could be the great depression again. Stocks could lose 90% of their value and stay low for a decade. It could even be the permanent unraveling of the US financial system. We can’t afford to bear that risk.” Indeed. Now, this institution should have realized this ahead of time and not set up an investment strategy that promised to wait out temporary mark to market losses. But the real question is not the ability to wait out temporary price dips. The real question is the ability to bear risk. Stocks were evidently a good deal in early 2009, but still risky and not a sure thing. The “long run investor” is one who could afford to stay in, and continue to bear the small risk of further declines in return for the large risk premium for not selling everything at the bottom, as my adviser did.

In sum, long-term US Treasurys are a great hedge against the following sort of event

A big recession

A financial crisis, in which the risk premium rises (credit spread rises, stock price-dividend ratio falls); and borrowing is constrained

Short-term interest rates plummet.

Protection against such an event however is most useful for investors who

Trade often

Are leveraged, and need to roll over short-term financing of longer-term positions

Use risky collateral

Follow carry trades, momentum, or other strategies similar to put writing, which unravel in this event

Have businesses or other affairs that suddenly need cash infusions in such an event

Cannot afford to take risk in such an environment, even if the prospective rewards are large. Must miss the buying opportunity of a century.

For the rest of us, who could simply sit it out, while hedging against a mark-to-market fall in our stock portfolios would have made us feel better, buying that insurance is not worth the substantial price. For the brave few who could still take on risk, December 2008-March 2009 was the buying opportunity of a century. While big endowments were selling, my friend Bob who runs a muffler shop was buying stocks. He made a lot of money.

3 Covid and inflation, 2020-2023

Well, lesson learned. Load up on bonds and get some insurance against recessions. Figures 4, 5 and 6 present the same graphs for the covid recession and subsequent inflation.

Figure 4: The macroeconomic situation. Unemployment and the CPI. Gray area is the recession. The vertical line is February 1 2021.

As shown in Figure 4, the covid recession was superficially similar to the 2008 recession. Unemployment spiked. Inflation declined from 2% to zero for a few months, and then stayed muted while the economy recovered.

The covid recession was different. Output fell because of a supply shock, not a financial crisis. I call it a snowstorm shock. Business is locked down by decree, and nobody wants to go out anyway. Output does not fall from a pure lack of “demand.” And when the snow melts, the economy goes right back to where it was, without the lengthy recovery from a risk premium or credit constraint recession. In the end, there was also no financial crisis, though whether this was a natural event or a result of the Fed’s massive interventions is a good question.

Figure 5: Yields. Gray area is the recession. The vertical line is February 1 2020.

In Figure 5 we see a pattern reminiscent of the crisis as well, though on a much smaller scale. BAA and AAA yields briefly rose, while treasury yields fell sharply, as the Fed once again dropped the Federal Funds rate to zero.

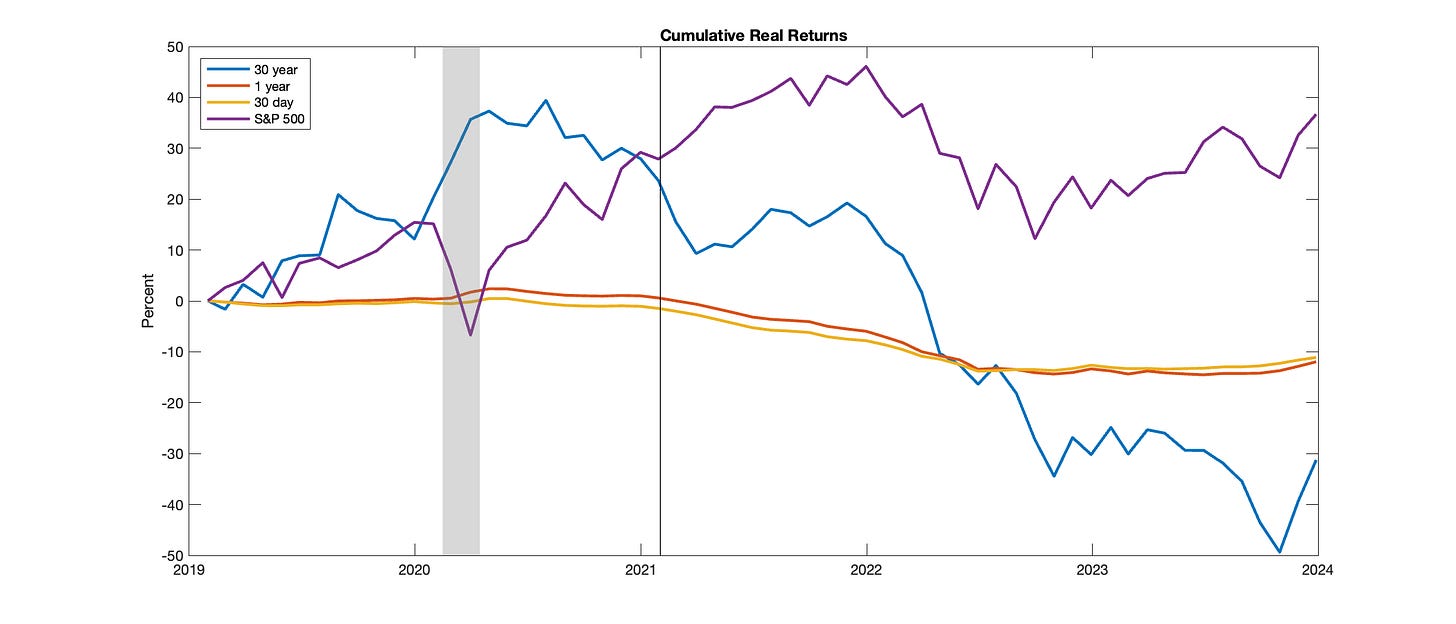

Figure 6: Cumulative log real returns on 30 year, 1 year and 30 day treasurys and the S&P500 index. Gray area is the recession. The vertical line is February 1 2021. Data source: CRSP.

In Figure, 6, stocks tanked, and the 30 year treasury rose nearly exactly as much. The combination of lower interest rates, which translated to a lower 30 year yield, and reduced inflation did its trick again to produce a lovely negative bond-stock correlation in this time of economic and financial stress. Once again, the stock market losses and bond market gains proved transitory, however, as stocks rose quickly once the pandemic faded, and bonds lost value as bond yields rose back to normal. Long-run investors who slept through the event did not need the bond insurance.

Again, the decline in inflation produced a small bump for short-term bond investors, but lower yields quickly started to eat at their cumulative returns.

3.1 Inflation

And then inflation hit. I draw a vertical line in February 2021 as the date when inflation broke out in order to better compare across graphs. In my analysis inflation broke out because the government printed up about $3 trillion of money, borrowed $2 trillion more, and sent people checks, with no indications how it might repay the increased debt. The large spending bills of early 2021 confirmed the expectation that no debt repayment was in sight. (See Cochrane 2022, 2023, 2024. Barro and Bianchi 2023 show that inflation across countries lines up with the size of their fiscal expansions.) Other stories, including monopoly, greed, and supply shocks, all confuse relative prices with the price level. Inflation is a decline in the value of money, period.

The source of inflation, however, is only relevant to the present analysis as far as it identifies the kinds of events which correlate with inflation-induced losses and inform states of the world in which investors are likely to bear such losses in the future. If you prefer a different explanation for inflation, then paste a different kind of future state of the world in which it will be repeated.

Figure 4 shows the surge and decline of inflation, measured conventionally as growth from the previous hear in the consumer price index. I also show the log level of the consumer price index. Many people and many more politicians confuse the easing of inflation, which has happened, with a return of the price level to its previous value, which definitely has not. To emphasize the impact of the episode, I draw a line of how the consumer price index would have evolved if it had grown at 2% starting in February 2021. The price level remains about 10% higher than this value.

The event was an increase in the price level. Cumulatively, inflation has eaten away 16% of the value of dollar securities since February 2021. If we think bondholders expected 2% inflation, then we conclude that inflation unexpectedly destroyed about 10% of the real value of bonds.

The Fed waited a whole year, until March 2022 to raise interest rates in response to inflation.

As we will see, this is an unprecedented and important delay. Even in the 1970s, the Fed never waited that long to respond to inflation. Remarkably, relative to standard doctrine, inflation started to decline just as the Fed began to raise rates, and with interest rates still 8 percentage points below inflation, and continued to ease despite no Phillips-curve recession. The federal funds rate did not exceed inflation until early 2023. In my analysis, the $5 trillion fiscal gift had pushed up the price level as far as it needed to go, so inflation eased on its own. The alterna- tive story is that the Fed’s demonstration of seriousness lowered inflation expectations, which lowered inflation.

Figure 5 shows bond yields through the episode. As a result of the Fed keeping short-term rates down, bond yields stayed low until very late in 2021, when it became clear that the Fed would indeed have to move. Then they all rose in tandem, reflecting higher expected future interest rates. Yield spreads remained the same, so the rise in yields imposed losses across all bonds.

Figure 6 adds up the damage by tracking cumulative real realized returns. The combination of 10% cumulative unexpected inflation and the rise in yields was a bloodbath for long-term bond investors, leading to continuously-compounded 50% loss in real returns. (It was also a windfall for homeowners who had taken out or refinanced into 3% 30 year fixed rate mortgages, but a severe shock to those like the Federal Government who tried to save a few basis points by borrowing short term or at floating rates.) (50% is a lot larger than the 10% cumulative rise in inflation so far, as the bond market is pricing in expected future inflation, and expected future higher real rates that may be necessary to fight inflation. It reflects the higher long-term bond yield, as well as the inflation that has devalued coupon payments so far.)

The stock market rose in 2022, then fell, somewhat paralleling bonds. Here we see the possibility of a positive bond-stock correlation. That is a natural result of a higher real rate of interest, which lowers bond and stock values together. Some shocks push stocks and bonds in the same direction, such as real interest rates. Some shocks push them in opposite directions, such as a rise in risk premium.

Intriguingly, short-term bondholders lost as well, with a cumulative -13% real return by the end of 2023. This event upends conventional bond wisdom. We usually think that inflation hurts long-term bondholders. But, when a persistent inflation breaks out, short-term interest rates must soon rise with inflation, so short-term bondholders will not suffer. In the presence of persistent inflation, they refuse to roll over debt at a low rate. In equations it = rt +Et 𝜋t+1 with it = the nominal short-term rate, rt = the real interest rate, and Et 𝜋t+1 expected inflation. Higher Et 𝜋t+1 raises the required it so that the real return rt is relatively unaffected by inflation. (At a monthly frequency, unexpected inflation is a minor issue in this sort of thinking.) That didn’t happen. In one interpretation, the Fed was able to hold down the nominal rate it to zero for a whole year, and below inflation for two years, resulting in a negative real return rt for short- term bondholders. We did not know the Fed was so powerful. The other interpretation is that short-term bondholders, like the Fed, kept seeing each month’s inflation as unexpected, so that expected inflation Et 𝜋t+1 never rose. But that explanation requires one-month bond investors to be surprised 24 times in a row, one-week bond investors to be surprised 104 times in a row, and overnight debt holders to be surprised 730 times in a row.

Whatever the explanation, the standard doctrine that short-term, even overnight, bond- holders will be protected from inflation because short rates will promptly rise with inflation is simply wrong. Call it “financial repression” if you will (as happened in the 1940s and 1950s), the government is able to impose inflationary losses even on short-term bondholders. Though they get repaid before inflation fully devalues their investments, unless they consume the entire pro- ceeds, they have to reinvest at low real rates of return, with nominal interest rates as much as 8 percentage points below inflation. This event changes the standard thinking about the relative risks of long and short term bonds.

3.2 The Future and the Distant (?) Past

The government basically financed about half of its Covid expenditures by inflating away the value of its debt. That loss fell harder on long-term nominal bond holders. It’s just as if the government had partially defaulted on that debt. Even if you subscribe to supply shocks, profi- teering, greed, or other explanations for inflation, it remains a fact that inflation destroyed a few trillions of dollars of bondholder wealth, and that the US government can pay back its remain- ing nominal debts with less valuable dollars. (Nominal tax receipts will rise automatically due to inflation.)

This event highlights the major risk facing long-term nominal government bondholders: In time of stress such as a pandemic, war, or major crisis, the government may inflate away or default on your debt to pay for a sudden (perceived) spending need. The US had major inflations in the Revolutionary War, the Civil War, WWI, WWII (masked by price controls and rationing, so the in- flation surged when these were lifted in 1947), and smaller inflations in the Korean and Vietnam wars. ( Hall and Sargent, 2014, draw the analogy between Covid inflation and those of WWI and WWII.) Other countries have done the same. In the sweep of history, that we regard government debt as “risk free” is a rare privilege of the post WWII calm. Defaults and inflations over the cen- turies, and in countries from Latin America to Greece today, have been an ever present risk. We take for granted that the US will always inflate rather than default, but explicit default is not as improbable as commonly assumed. The US defaulted before, on the gold clauses in the 1930s for example. When a crisis comes, and this time the Federal Reserve declines to purchase vast amounts of new debt, will our Congress really prioritize paying interest and principal to bond- holders, perceived as wall street bankers and foreigners, over writing checks to needy Americans, or paying for vital programs including defense? Statements by Treasury officials during debt limit negotiations have explicitly threatened default.

Figure 7: Debt to GDP ratio, as projected by the Congressional Budget Office. Source: CBO Long- Term Budget Outlook: March 20, 2024.

Figure 7 presents the CBO’s projection for the US debt to GDP ratio. This fiscal trajectory is unsustainable. And the CBO’s projection is optimistic on a number of dimensions. It includes current law, for tax increases and spending cuts that we know won’t happen. Most of all, it as- sumes nothing bad ever happens again. Note the last two big runups in debt, during the financial crisis and the pandemic. (The recent reduction comes from inflating away debt, not paying it back.) During the next big crisis, which will surely happen sooner or later, the US will want to borrow or spend another, say $5 trillion or more, to finance bailouts, stimulus, and perhaps military expenditures. Markets, chastened by how quickly the last such adventure turned in to inflation, may balk.

Why are interest rates so low, you may ask? Well, investors either think they can get out before everyone else when the next crisis looms. Or, more likely in my view, perhaps they under- stand that this is a self-inflicted wound, and surely Washington will get around to straightening out its finances before it sends this great country in to a debt crisis or sharp inflation; doing the right thing, as the saying goes, after trying everything else.

Still, as 1979 followed 1975, a repetition of the 2021-2023 inflation, provoked by the next crisis, or even the Fed’s apparent return to 1978 monetary policy, is not an event that prudent risk-management should ignore.

But is this a priced risk? When we decide what return and yield we demand before taking on a risk, the likelihood of risk (volatility) matters, but so does the state of the world in which the risk manifests, the beta of the risk. As we saw, bonds are useful hedges to some classes of investors because they do well in specific times that are otherwise particularly painful for those investors. Is an inflation-induced loss a particularly painful time for you? If not, yes, insist on a premium that compensates for the probability of inflation. If you think there is a 10% probability of 10% inflation over the next 10 years, then don’t invest in nominal bonds unless the yield is 1% higher than your target risk free real return. But inflation comes with particularly painful other events in your financial life, insist on a good deal more.

The standard Phillips curve picture of boomflation suggests that inflationary looses come in good times, when the stock market is high and the economy doing well. If so, a small or even negative premium is appropriate. This may be an explanation for low average returns of government bonds, another negative beta. But inflation that comes in a time of crisis, war, or economic emergency is likely a strong positive-beta force. Bonds do badly exactly when having something in your portfolio that does well would be convenient.

4 The great inflation and disinflation

Now that you mention inflation, what are the lessons of the last great inflation and disinflation in the US from the late 1960s to the late 1980s? Figures 8, 9, and 10 show the same data for that period.

Figure 8: Inflation and federal funds rate

There were three waves of inflation. For clarity, I only show the 1975 and 1980 peaks, and the disinflationary 1980s that followed. In both 1975 and 1979, inflation surged despite the Fed rais- ing interest rates much more promptly than in 2021-2023. In 1975, inflation eased even though interest rates fell first. Inflation stabilized at a somewhat higher level than before, before shoot- ing up again starting in 1978. That ought to be a worrisome scenario today. Inflation peaked in 1980. Its decline coincided with very high real interest rates (the fed funds rate line is above the inflation line) that lasted, with one interruption in the early 1990s, until the new century. No surprise, that was a great time to hold bonds. It was also a boom, however, so counts as a positive beta event.

Conventional wisdom attributes the inflation decline entirely to determined and tight monetary policy, and this episode alone accounts for current beliefs in the power of monetary policy. However, the 1980s also included important fiscal and microeconomic reforms, leading to a booming economy and surging fiscal surpluses. In my view, this disinflation, like all successful disinflations, combined fiscal, monetary, and microeconomic reform.

For investment purposes, the correlation is enough: 1970s inflation rose during recessions, “stagflation.” 1980s disinflation accompanied a strong economy, “boomflation.”

Figure 9: Bond yields

Bond yields in Figure 9 show some of the familiar patterns. Credit spreads rose in the 1975 recession, as the 10 year rate stayed steady and the short term rate declined. Credit spreads widened again in 1982, but stayed permanently high, and the rise did not correlate well with the decline in 10 year yields. There was little rise in credit spread in 1992. These recessions did not involve extensive financial crises, so the “negative financial crisis beta” of 2008 is small and hard to see.

Figure 10: Cumulative returns (log)

Cumulative returns in Figure 10 start with the bloodbath of 1974-1975. (The figure plots log returns. The arithmetic loss 1−exp(−0.7) = 0.5 is a bit less dramatic. But losing half your wealth is still the worst time in the stock market since the great depression.) Due to inflation and rising interest rates, long term bonds fell as well. And it was surely a bad time to lose money, in addition to stock market losses. Again, inflation and recession add up to a positive bond beta. The pattern repeats in 1980, and the huge boom in both bonds and stocks that follows. Short term bonds provide only a muted version of the same story.

The graph reminds us that long term assets bear real risk. We talk about temporary bond and stock market declines, but a 1972 investor did not see a positive total real return until the mid 1980s. And stocks did not make up the catastrophic loss of 1974 relative to bonds until the end of the century. The equity premium is large over long periods of time, but “long” can mean over 30 years.

5 Lessons

So, sometimes bonds have negative beta and are hedges, relative to stocks or credit and (I keep stressing) more importantly relative to the larger economic “state variables” that define when many investors particularly value positive portfolio returns that might offer some insurance value. And sometimes bonds are risky assets, doing well only when everything else is doing well and tanking just like everything else in bad times. The financial crisis and flight to quality of 2008 is a prime example of the former. Stagflation and a potential debt crisis are a prime examples of the latter, with economic boom, solid public finances, and disinflation the other side of the coin. How can we tell which applies now and to us?

The conventional approach to this question describes a time-varying correlation between bonds, stocks, and the economy, as an economic fundamental. The correlation changes, you’d better bone up on your statistical models of time-varying conditional covariances.

I think this is largely a mistake. It is more productive to think of an economy as funda- mentally a stable structure, but hit by different shocks. Figure 11 illustrates the general point.

Figure 11: Supply and demand illustration

Sometimes prices and quantities rise and fall together. Sometimes prices rise when quantities fall. Should we think of the economy as having a time-varying correlation between prices and quantities? No, the fundamental structure – supply and demand curves – is the same. When demand varies more than supply, prices and quantities move together. When supply varies more than demand, prices and quantities move in opposite directions.

A similar lesson applies directly to time-varying correlations. It is said that “correlations increase in downturns.” But this behavior results from a stable structure and different shocks. Think of any standard factor model, in which the return of a security (say, a stock) is driven by factors (say, the market), plus idiosyncratic variation. If there is a big factor (market) return, and idiosyncratic returns are the same as usual, securities will move together more than usual. If the factor is quiet, then the idiosyncratics drive asset returns, which naturally become less correlated. The factor structure is stable over time, just hit by differing factor vs. idiosyncratic shocks.

I find it more productive to analyze the time-varying correlation of bonds with stocks – and, again, with other state variables of deeper concern to investors – in this way. I also find it more productive to try to name economic events rather than take asset correlations as a somewhat mysterious primitive. What kinds of shocks generate a positive correlation, and what kinds of shocks generate a negative correlation? Then we can more productively think about what kind of economy we are likely to live in for the next decade or so.

5.1 Investment opportunities and long vs. short term bonds

Once again, stock market beta is not the right measure of risk for most investors. Most investors care about how an investment adds or subtracts to the overall risk of a portfolio that includes business income, private equity, a liability stream, or a portfolio that deviates from market weights for a variety of reasons.

And many investors care about the long run. A decline in an asset’s value that comes with a rise in its expected return, meaning the price will bounce back, does not affect a long-run investor. If you have a 30 year investment horizon, a 30 year inflation-indexed bond is the riskless asset, not cash. It will have frequent large price declines, but you do not care. Each price decline comes with an increase in yield, and no change in the payout in 30 years. Short-term indexed bonds appear risk free, but that’s only at short horizons. The 30 year payout of short term bonds is volatile, because interest rates rise and fall during that time. A period of high interest rates raises the 30 year return; a period of low interest rates lowers that return.

More realistically, long-run investors desire a stream of income, not a lump sum in 30 years. For them, the risk free asset is not cash, but an indexed perpetuity. (Campbell and Viceira, 2001.)

If you object, “I might have to sell before maturity,” then you’re not a long-run investor. Short-run investors, including leveraged traders and arbitrageurs, care very much about short-run price fluctuation even if it will reverse over time. The market includes both kinds of investors. If everyone else is a short-run investor, there will be good opportunities for long-run investors who can ignore or even buy the dips of temporary price fluctuations. And vice versa.

There are two complementary ways to think about this issue. Merton (1969) formalized this insight 50 years ago, by adding to the concept of betas. Long-term investors care about betas with respect to investment opportunities, not just betas with respect to the stock market. An asset that pays off poorly when investment opportunities rise (the 30 year bond) is not so bad. An asset that pays off well when investment opportunities rise is golden. Long term indexed bonds are risk free for long-run investors because they have a strong beta on yields. When prices decline, yields rise. This seems conceptually hard to do. Alternatively, one can simply focus on long-run risk and return directly. That seems technically hard to do.

Either way, this fundamental issue is largely ignored in practice. But it is insane to evaluate bond strategies for long-run investors with one-period means, variances, alphas, and stock-market betas.

With that background, what are the risks and rewards of long-term vs. short-term nominal bonds for long-term investors?

• If real interest rates vary, and inflation is stable, then long-term nominal bonds are safer than short-term bonds for a long-term investor. If real interest rates are stable but inflation varies, then rolling over short-term bonds is safer for a long-term investor. The nominal short-rate will rise with inflation.

In a market dominated by long-term investors, we then expect that the yield curve will rise if interest rate changes are dominated by changes in inflation, and the yield curve will fall if interest rate changes are dominated by real rate changes. The yield curve sloped downward under the classical gold standard, for example.

In reality, we never see just one thing move, as we never see only the supply or demand curve move. The events that cause inflation also can cause real rates to change, and events that cause real rates to change can cause inflation. As we saw vividly in 2023, short-term interest rates do not always rise swiftly with inflation. Still, the three year delay did not impose on short-term bondholders anything like the losses that long-term bondholders felt.

5.2 Stocks, credit, and bonds

The expected return on stocks is driven by real interest rates plus a risk premium. Stock prices are driven by the expected return – higher expected return means lower prices, as higher bond yields means lower bond prices – plus cashflows, current and expected dividends. So, broadly three separate kinds of shocks drive stock prices and returns.

Government bond yields are driven by real interest rates and inflation. Risky bonds add a risk premium. So in our supply-demand framework, we see how each of these forces moves stock and bond returns differently.

If the real interest rate rises, holding other influences constant, both stocks and long-term bonds decline in value. So,

• Real interest rate variation induces a positive stock-bond correlation. If the risk premium rises (2008), stocks and risky bonds decline, but government bonds are unaffected, a zero beta.

Higher real interest rates can be a sign of good times or a cause of bad times. If real investment opportunities improve, and more investment capital is needed to take advantage of them, then real interest rates will rise. Interest rates and investment rise together. Better investment opportunities also raise the expected cashflows of stocks, so stock prices rise from the cashflow effect even if dampened by higher interest rates. So the advent of an economic boom is likely to be initially neutral for stocks and lower long-term bond prices, followed good returns.

Higher real interest rates can also cause an economic downturn, for example if the Fed tight- ens policy. In this case, higher interest rates bring lower investment. Such a downturn hurts both stocks and bonds and drives a positive bond-stock correlation. More importantly, the event is a bad time for most investors.

The Fed of course reacts to economic events. We see the mixed possibilities daily. Some- times good economic news lowers stocks. Why? Because markets think it will provoke the Fed to raise interest rates, and the discount rate effect outweighs good cashflow news. Sometimes good news raises stocks, because the balance tips toward the cashflow news.

Higher risk premiums seem to occur during economic downturns, and during financial crises which are broadly a reduction in the risk-bearing capacity of the financial system. Thus, they are more clearly times of stress, higher marginal utility, for the average investor and times that they would dearly like securities not to fall. Higher risk premiums clearly lower stock and risky bond prices, the former amplified by a negative cashflow effect and the latter by higher default probabilities. But for investors unaffected by the economic situation and who do not need leverage, a time of higher risk premium is the time to invest. Your fire sale is their buying opportunity.

Higher risk premiums by themselves have no effect on bond prices. However higher risk premiums or the associated economic events usually induce lower interest rates and higher prices on government bonds. That happens both from the “flight to quality” against limited supply of government bonds, and because the Fed usually swiftly lowers interest rates. Inflation usually also falls. These events, as in 2008, generate negative stock-bond correlations, and more importantly the value of government bonds as hedge assets.

5.3 Spreads and trades

So far, I have focused on the concerns of portfolio investors, including individuals and institutions, with long horizons, limited high frequency trading, and important business, outside investments, or liability streams. A completely different strand of thinking is appropriate for those seeking to actively trade in bond markets.

The plot of Baa and Aaa yields along side long-term government yields offers them a seductive opportunity. Forget all this long-run stuff. There is a 1-2% yield spread between essentially identical securities. If you could borrow at the treasury rate and invest in these securities, you’d make a killing. That attitude encompasses a large amount of fixed income trading, including spread trades between short run and long run, liquid vs. illiquid, on the run vs. off the run, high interest countries vs. low interest, and so forth. Most of these strategies resemble writing index puts: They earn a steady return (“carry”) for a long time, but occasionally have massive losses, and just at the most inconvenient times. Those losses are often temporary, reversing themselves after a few months, as they did in the 2008 “flight to quality” episode. But they wipe out highly leveraged traders. Nonetheless, returns may be positive even accounting for the occasional losses.

The persistence of these yield spreads has attracted a large academic following. On-the-run US treasury securities, in particular, seem to have a “liquidity discount” of as much as a percent- age point over comparable securities (Longstaff 2004, Krishnamurthy and Vissing-Jorgensen 2012). People hold them as they hold cash and checking accounts, suffering a bit of interest loss in return for the ability to sell quickly if needed. Treasury debt is useful as collateral, and this “collateral scarcity” drives down its yield. This “liquidity demand” is different from “negative beta,” the fact that these securities rise in price in bad times.

I do not here try to offer investment advice for high frequency traders. But what do these observations, if true, mean to long-run investors? First, it means that the market contains people with such “liquidity demands,” that drive down treasury yields. As always, thinking about who else is in the market and how they drive prices helps to understand where there might be opportunities. You can’t arbitrage that spread, but you can avoid assets with liquidity discounts. Don’t hold a long position in the short end of a near arbitrage opportunity. Why, then, do pension funds, insurance companies, other institutions and long-run individual investors buy on-the- run treasurys, paying a liquidity premium, when they will not sell the securities for years? Don’t buy liquidity you don’t need. There is a good economic argument that illiquid debt such as private debt can generate a better long-run return.

Second, if these observations are true, it implies that not enough money is flowing in to arbitrage activity. Equity positions in arbitrage should provide handsome alpha. Alas, though each issue of each academic finance journal has 9 papers that claim to find market mispricing and arbitrage opportunities, it usually has one paper examining the real world performance of active managers, which regularly reports the near absence of any alpha.

6 Investment advice

You will notice a decided lack of definitive quantitative and actionable portfolio advice in this essay. That is a large part of the point.

Portfolio calculations offer one size fits all advice for the mythical investor whose objective is entirely the one-period mean and variance of portfolio wealth, not lifetime income; who has no job, outside income, outside investments, business, or liability stream; facing a well defined statistical model of asset returns and correlations. That assumption does not match most investors, statistical models are unreliable, and the 70 years of following this approach has not produced useful advice, or even much documentable alpha for those who want alpha.

Instead, I emphasize two crucial facts: 1) Investors are different, and 2) The average investor holds the market portfolio. As a result of the second fact, if we were not different, then portfolio advice could not be other than to hold the market portfolio as cheaply as possible. Since investors differ, however, asset markets offer a healthy opportunity to buy and sell insurance. Investors who buy long-term bonds for their insurance against financial crises obtain them at low cost from investors who can hold risky assets through such events, and underweight them. Investors who will ride out an inflationary event buy bonds from investors who will be wiped out by inflation. And so forth. Since average returns and correlations are hard to measure, understanding where a given investor lies in the spectrum that determines market prices is helpful to make such decisions.

To answer the motivating question, bonds are both hedges and risky investment opportunities. In a nutshell, government bonds offer insurance against flight to quality events, useful for some kinds of investors. Bonds offer a return that can be as good as stocks, as seen from 1970 to 2000, in return for the risk that the government will not inflate them away in a crisis. Caveat emptor.

That sounds awfully hard, you say. I agree. But hard is an opportunity. Academic research resolutely fails to find any alpha in the active management industry. So what do institutions charge fees for? Well, matching up investors to the opportunities that are appropriate for their situation is hard, and requires expertise. But unlike alpha-chasing, it is a positive sum game. Appropriately matching investors to their assets can make everyone better off. And it works in a perfectly efficient market, which displays no alpha. This activity is a perfectly sensible reason for fee-charging investment management to prosper, if it’s done right.

References

Barro, Robert J. and Francesco Bianchi. 2023. “Fiscal Influences on Inflation in OECD Countries, 2020-2022.” NBER Working Paper 31838 URL 10.3386/w31838.

Campbell, John Y., Carolin E. Pflueger, and Luis M. Viceira. 2020. “Macroeconomic Drivers of Bond and Equity Risks.” Journal of Political Economy 128:3148–3185.

Campbell, John Y. and Luis M. Viceira. 2001. “Who Should Buy Long-Term Bonds?” American Economic Review 91:99–127.

Cochrane, John H. 2011. “Discount Rates: American Finance Association Presidential Address.” Journal of Finance 66:1047–1108.

———. 2021. “Portfolios for Long-Term Investors*.” Review of Finance 26 (1):1–42. URL https: //doi.org/10.1093/rof/rfab038.

———. 2022. “Fiscal Histories.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 36 (4):125–146.

———. 2023. The Fiscal Theory of the Price Level. Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press.

———. 2024. “Fiscal Narratives for US Inflation.” Manuscript URL https://www.johnhcochrane. com/research-all/sims-comment.

Hall, George J. and Thomas J. Sargent. 2014. “Fiscal Discriminations in Three Wars.” Journal of Monetary Economics 61:148–166.

Krishnamurthy, Arvind and Annette Vissing-Jorgensen. 2012. “The Aggregate Demand for Trea- sury Debt.” Journal of Political Economy 120:233–267.

Longstaff, Francis A. 2004. “The Flight-to-Liquidity Premium in U.S. Treasury Bond Prices.” The Journal of Business 77 (3):511–526.

Merton, Robert C. 1969. “Lifetime Portfolio Selection under Uncertainty: the Continuous-Time Case.” The Review of Economics and Statistics 51:247–257.

What a detailed and insightful examination of bonds! This is much appreciated.

I started buying 30 year treasuries in 1995, and sold them all at their top in 2009-12. After that I increasingly concentrated on investment grade corporates, which until the debacle of 2020-22 were providing income similar and in some cases better, to some of the stock indexes.

Since then I have wondered where it is all going and where to go.

I shall further now reread this column at least once more and think of the comments Christine LaGarde made in the Financial Times this morning. She asserts that we are in a similar period to that of the 1920´s in three defined ways.

We all know how that ended.

You ask, “What kinds of shocks generate a positive correlation, and what kinds of shocks generate a negative correlation?” Arthur Laffer wrote presciently that when stock and bond prices move together it’s because inflation expectations are changing. If the correlation is negative, growth expectations are changing.