1951

What happened in the great tussle for Fed independence in 1951, and what lessons does that have for today? A colleague shared with me a great article “The Treasury-Fed Accord: A New Narrative Account” by Robert Hetzel and Ralph Leach in the 2001 Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond Quarterly Review.

After World War II ended, the Fed continued its wartime pegging of interest rates. The Treasury-Fed Accord, announced March 4, 1951, freed the Fed from that obligation. Below, we chronicle the dramatic confrontation between the Fed and the White House that ended with the Accord.

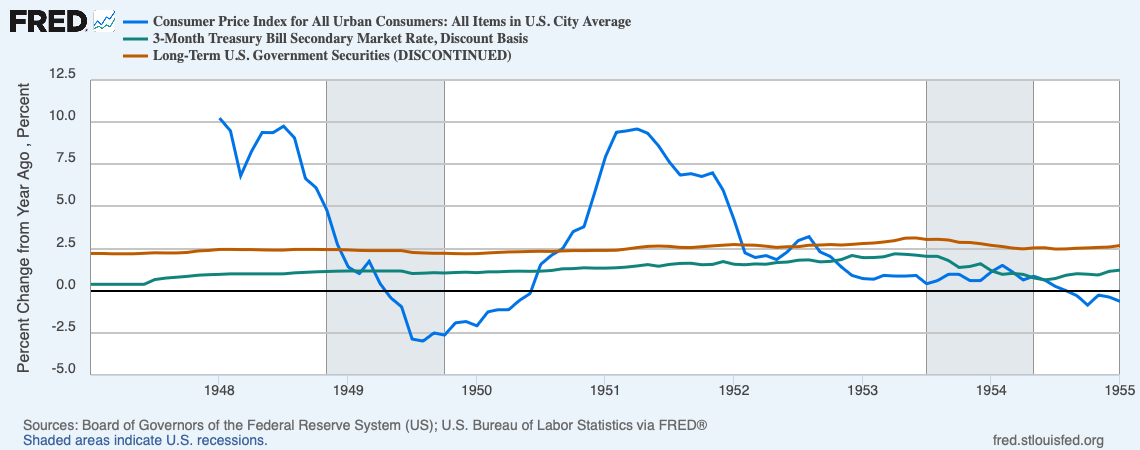

The Fed pegged long term interest rates at 2.5% during WWII, to hold down interest costs and keep up the prices at which the government sold debt. Inflation surged in 1947 and 1948 when price controls were lifted, but inflation quickly came down again once the price level had caught up. The Fed already wanted to raise rates in the recovery of 1950. The resurgence of inflation during the Korean War in 1951 set the stage for the great battle for independence: Would the Fed continue to peg at 2.5%, printing money to buy bonds as needed? Or should the Fed’s job to contain inflation take precedence? (More technically, the Fed exchanged bonds for bank reserves, accounts banks hold at the Fed, which are freely transferrable to cash and before 2008 did not pay any interest.)

The article is notable for the politics of the “tussle” between Fed and Treasury, which I heartily recommend. I focus more on the economic issues.

Why did inflation break out in 1951?

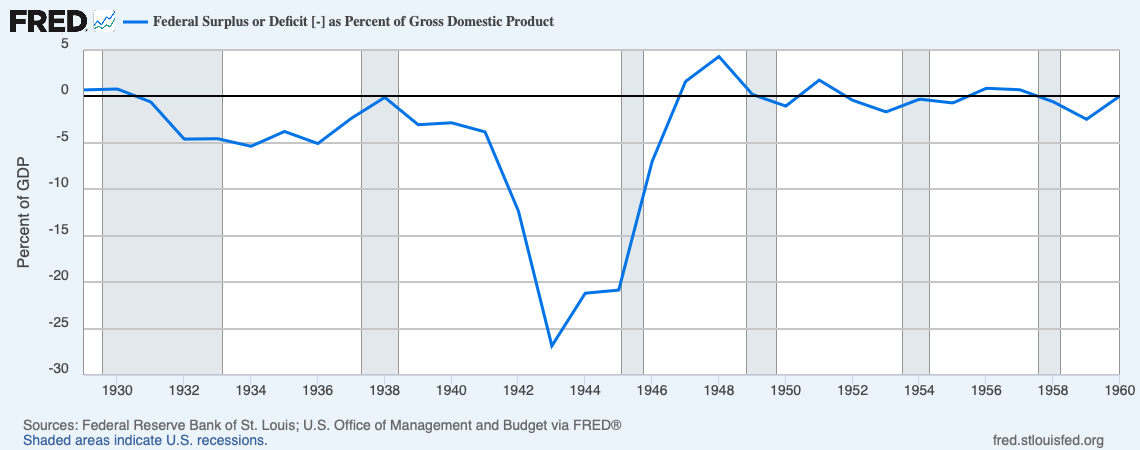

Interestingly, the Truman administration was not running deficits to fight the Korean War. It planned to finance the war through current taxes, unlike the standard (today) economic advice.

Truman and the leadership in Congress believed that deficit financing had caused the World War II inflation… At the urging of the Administration, Congress raised taxes sharply in September 1950 with the Revenue Act of 1950 and again in January 1951 with an excess profits tax….

My graph is the total deficit, including interest costs on the debt. The latter are a back of the envelope 2.5% x 80 = 2% of GDP, so the primary surplus is positive throughout. The fiscal issue was not issuing new bonds or financing new deficits, but just prices of outstanding bonds and a bit of roll over. The Fed was not printing up money to finance new bond sales. If you like Phillips curves, the economy was growing, but not 10%-inflation booming.

However, we forget now how uncertain the world was at the time. There was a justifiable fear that the Korean War would quickly spiral to become WWIII against the USSR and China.

On November 25 and 26 [1950], the Chinese army, 300 thousand strong, crossed the Yalu River. Suddenly, the United States faced the possibility of a war with China and, if the Soviet Union came to the aid of its ally, of World War III… Anticipating the reimposition of wartime controls and shortages, consumers rushed out to buy consumer durables. On world markets, commodity prices soared. For the three-month period ending February 1951, CPI inflation was at an annualized rate of 21 percent.

…The prospect of a prolonged war created the likelihood of government deficits and the issuance of new government debt. Additional debt would force down the price of debt unless the Fed monetized it…

The rational-expectations fiscal theorist smiles. Prospective future deficits, and the likelihood of future price controls and rationing are pretty clearly the impetus for a surge of inflation.

Why did inflation go away?

The article does not remark on it, but look back at my graph of interest rates and inflation. One would expect that inflation surges to 10%, the Fed wins the battle over the 2.5% peg, the Fed swiftly raises short term rates to above 10%, long term rates surge on their own to wherever they were headed absent Fed pegging, and we repeat 1980 to get inflation under control.

Nothing of the sort happened. You can barely see the long-term rate cross the 2.5% line. You can barely see short term rates rise at all. There was no recession. Inflation just melted away.

The fiscal theorist smiles again. By June 1951, the odds of all out war with China and the USSR had clearly diminished. A one-time fiscal shock creates a one-time surge of inflation, just as in 2021-2022.

The other narrative is “whatever it takes,” restored credibility. On the publication of the accord, people believed that the Fed would, in teh future, raise interest rates as needed to control inflation, so the Fed didn’t actually have to do anything, and inflation goes away on its own.

If you like to think in terms of Phillips curves, inflation = expected inflation + k x output gap. There was clearly no high lowering the output gap, so just as clearly the news of mid 1951 changed expectations. Rational expectationsers can smile in any case; beyond that the fiscal vs. Fed story is an interesting debate.

Why not raise rates?

Why was the Treasury so keen to maintain the peg? Again, there were no large current deficits, so it was not to issue new bonds at high prices. Interest costs on long-term debt are locked in, so only relatively small re-funding of short term debts impinges on the budget.

The article mentions two concerns. First, the Treasury wanted to keep up the secondary market prices for the bonds, so that those who bought bonds in WWII could sell them for good prices rather than wait for maturity.

Truman felt that government had a moral obligation to protect the market value of the war bonds purchased by patriotic citizens. He talked about how in World War I he had purchased Liberty Bonds, only to see their value fall after the war.

Interestingly, Truman did not feel that permanently devaluing the same bonds through inflation was such a bad thing.

The other consideration is that the Treasury knew full well that though Truman might finance Korea with current taxes, WWIII was going to take borrowing on a massive scale:

The Treasury wanted the Fed to commit publicly to maintaining the existing interest rate structure for the duration of hostilities in Korea. In early December, President Truman telephoned Chairman McCabe at McCabe’s home and urged him to “stick rigidly to the pegged rates on the longest bonds.” McCabe replied that he “could not understand why we would. . . allow the life insurance companies to unload [their bonds] on us” (FOMC Minutes, 1/31/51, p. 9). Truman followed up by writing McCabe: [T]he Federal Reserve Board should make it perfectly plain. . . to the New York Bankers that the peg is stabilized.. . . I hope the Board will. . . not allow the bottom to drop from under our securities. If that happens that is exactly what Mr. Stalin wants. (FOMC Minutes, 1/31/51, p. 9)

The Fed was not preparing for the next war.

All in all, was Truman wrong?

If Korea had turned in to a long, expensive war, surely the US would have turned to war finance again: spend like crazy, borrow, print, hold down rates, and eventually price controls; some inflation implements a state-contingent default. Maybe Truman’s “geostrategic” view wasn’t so dumb after all, at least before it was clear WWIII would not break out.

This is the major issue before us now for Fed independence. It’s not the Phillips curve, or how soon the Fed should adapt to a forecast productivity increase due to AI.

Suppose a major crisis breaks out, like a Taiwan blockade or heaven forbid a war. The US will want to invoke war finance again as it did under Covid; just as it might have had to do in Korea, and as it did in WWII. Spend, borrow, Fed buy a lot of debt to hold down rates, and eventually regulations and controls to force people to hold that debt. A bit of inflation be damned. We didn’t want to lose WWII on the altar of no inflation.

The Fed went along in Covid as it did in WWII. It might want to fight that inflation in the next crisis as it decided it wanted to fight inflation during the Korean War. Does the Congress really want the Fed to do that, refuse to buy debt, let long and short term rates rise, and make the crisis fighting effort all that much harder?

I actually think the Fed should be much tougher than it was in Covid, and much tougher still in the post-covid blowout. It should fight back hard on all the fiscal excesses that the US tends to in time of crisis. But that is an issue we should debate.

Lots of other interesting economic issues percolate through the article. Plus ça change.

Whatever it takes

Again, the pressing issue was not financing new debt, but rather managing the outstanding debt and to a lesser extent rolling over short term debt.

Throughout 1950, the 2 1/2 percent ceiling on bond rates had not been binding.. Eccles advocated that their price be allowed to fall somewhat so that they would trade just below 2 1/2 percent.

That fall in the bond price would still leave in place the sacrosanct 2 1/2 percent rate peg. However, it would address [I think this is a typo and the authors mean “create”] an immediate problem. The threat of a major, protracted war created the real possibility that the bond rate would rise to its 2 1/2 percent ceiling. Life insurance companies, which held the bonds, then had an incentive to sell them immediately to avoid a capital loss as bond prices declined. The Fed did not want to monetize an avalanche of bond sales [to enforce the peg]. …. The Treasury, in contrast, saw the problem as one of the Fed’s own creation. If the Fed would only publicly commit to maintaining indefinitely the current price of bonds, it believed, bond holders would no longer have an incentive to sell.

“Whatever it takes” had better be whatever it takes. Then it doesn’t take a lot. If you waver on a peg, it takes a lot more.

the FOMC then reduced slightly its buying price for long-term bonds. Secretary Snyder saw that action as creating a fear of capital loss that hindered the success of the refunding.

An upward sloping demand curve for bonds. If you lower the price, you reduce demand as people fear more price declines.

Monetarism foreshadowed?

The article presents the Fed as thinking in surprisingly monetarist terms, given that this was 1951. Some of that may be the author’s interpretation, but some of the quotes document that view too.

It was not private speculation or government deficits that caused inflation, but rather reserves and money creation by the central bank. Eccles said:

“[We are making] it possible for the public to convert Government securities into money to expand the money supply.. . . We are almost solely responsible for this inflation. It is not deficit financing that is responsible because there has been surplus in the Treasury right along.”

The latter point is right. It’s not ISLM flow deficits for sure. But prospective future deficits, well, one can excuse a central banker in 1951 for not thinking of that one!

Footnote 10 adds, after a long discussion,

Fed economists thus recognized the importance of monetary policy and its relation to inflation some 20 years before the economics profession began to debate seriously that possibility.

and

On January 25, Governor Eccles…testified:

“As long as the Federal Reserve is required to buy government securities at the will of the market for the purpose of defending a fixed pattern of Interest rates established by the Treasury, it must stand ready to create new bank reserves in unlimited amount. This policy makes the entire banking system, through the action of the Federal Reserve, an engine of inflation. (U.S. Congress 1951, p. 158)”

However, as you apply the lesson to today, remember that today the Fed pays interest on reserves, and back then it did not. Buying long term bonds and issuing interest-paying reserves is not so obviously inflationary. On the other hand, it’s not obvious that the Fed could peg long-term nominal rates in that fashion. The Fed bought finite quantities of bonds in the QE effort to lower long-term rates, and possibly so we and it would not test the limits of its pegging abilities. The Bank of Japan recently tried to peg long-term bonds and gave up.

Carter’s credit controls foreshadowed:

“The Treasury maintained the position that direct controls on credit were preferable to increases in interest rates (FOMC Minutes, 3/1/51, p. 117). “

Independence restored

Again, do read the article for the political tussle. Great tactics: if you want someone to do what you say, leak that they have agreed to the press. Then it’s much harder for them to say no, you didn’t agree. In the end, Truman gave in because his general political standing fell after firing MacArthur.

After the Fed won the battle, its Chair Thomas McCabe resigned, feeling fatally wounded by the tussle. President Truman appointed Assistant Secretary of the Treasury, William McChesney Martin.

“Leach recalls that the initial reaction both among Board staff and on Wall Street to Martin’s appointment was that the Fed had won the battle but lost the war. That is, the Fed had broken free from the Treasury, but then the Treasury had recaptured it by installing its own man. However, as FOMC Chairman, Martin supported Fed independence. Some years later, Martin happened to encounter Harry Truman on a street in New York City. Truman stared at him, said one word, “traitor,” and then continued.” Leon Keyserling (1971, p. 11), chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers from 1950 through 1952, said later: “[Truman] was as strong as any President had ever been in recognizing the evils of tight money.. . . He sent Martin over to the Treasury to replace McCabe. Martin promptly double-crossed him.”

In his speech accepting an appointment to the Board of Governors, Martin (1951, p. 377) said:

“Unless inflation is controlled, it could prove to be an even more serious threat to the vitality of our country than the more spectacular aggressions of enemies outside our borders. I pledge myself to support all reasonable measures to preserve the purchasing power of the dollar.”

Martin here reflects some of my own hawkish views. Don’t state-contingent-default too often. Here he is also explicitly addressing the “geostrategic” consequence of too easy inflation. A great reputation for repayment might be a better way to borrow a lot in the next war than too-quick financial repression.

The analogy for our own time is fun to think about. Trump is the obvious politician who “recogniz[es] the evils of tight money.” Powell, like McCabe, is the Fed chair, who experienced a lot of inflation mostly not his fault in my reading — the $5 trillion unfunded fiscal blowout, and the confidence-destroying additional Biden-era spending would have been hard for any Fed to fight. Like McCabe, Powell has been a powerful and courageous force for keeping the Fed independent. Kevin Warsh, who I playfully think of as the Dog Who Caught The Car for all the troubles he will face going ahead, is the obvious Martin analogue. And it is certainly quite possible that he will follow suit in Martin’s role. Trump is certainly more locatious in his disapproval than Truman!

Update

On independence and history, don’t miss Ed Nelson’s excellent new paper “The Practice of U.S. Monetary Policy Independence from Martin to Greenspan.” Ed is a master of economic and institutional history. He starts with 22 — 22! — common fallacies about Fed independence.

The Martin-Truman story reminds me of Thomas Beckett and Henry II. Henry appointed his friend (and carousing partner) Beckett to head the Church of England, with which Henry had been feuding, in the belief that his friend would do his bidding. Instead, Beckett transferred his loyalty to the institution he had been chosen to lead and fought Henry tooth and nail. Henry considered him a traitor, and acting on his heavy hint, several knights murdered Beckett.

No, Truman did not muse "will no one rid me of this meddlesome banker," resulting in a hit, but he like Henry ignored the fact that people who serve an institution have strong tendencies to have far stronger loyalties to it than to the person who appointed them to it.

Trump should heed those lessons, but probably won't.

Fascinating historical reflection, article and commentary whether viewed through the lenses of rational expectation fiscal theorist, monetarist, or Austrian ... and yes, which way Warch will "blow" is an interesting question of the day.